When an explosion occurred in lower Manhattan on Thursday, the usual coterie of reporters, photographers, and camera people rushed to the scene. I know this because there was another class of observers with them—regular people, using their smartphones to stream the event, live and unmediated, to the Internet. Quickly, pundits in the tech press proclaimed we were witnessing the birth of a new kind of news. This form of video distribution, Owen Williams argued in Next Web, “is absolutely going to change the way news is viewed and created.” If he’s right, that change isn’t a welcome one.

These video streams came to us thanks to a dueling pair of iPhone apps, Meerkat and Periscope. As Slate’s Will Oremus recently explained, Meerkat allows users to stream video directly to their Twitter followers, providing both a technological platform and a built-in audience. Though he suggested that it was more likely to fit into the existing social media landscape than to upend it, he acknowledged that it might also offer a new dimension to live events. Of course, the technology is not new—people used sites like Livestream and Ustream to broadcast during protests in Ferguson and elsewhere—but these new apps help to incorporate live streaming into the existing social media landscape, potentially bringing it to a much larger audience. When the Twitter-owned Periscope launched on Thursday, countless users immediately took to both apps to discuss their differences and debate their merits. Later, when news of the explosion spread around the East Village, Meerkat and Periscope streamers knew what to do.

Photo composite by Slate.

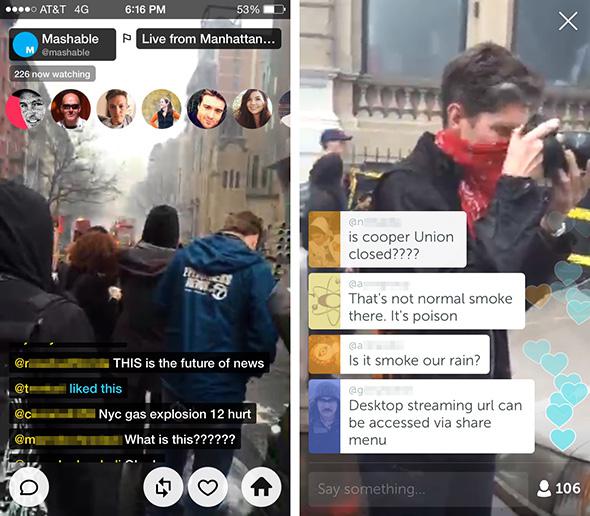

Meerkat and Periscope are remarkably similar. Their resemblance is immediately evident in their names: Both describe things that rise up to survey the scene. Both also look similar, thanks in part to the steady stream of comments from viewers that they superimpose over the lower half of the image. Immanuel Kant once argued that the way the rest of Europe observed and discussed the spectacle of the French Revolution was as important as the revolution itself. On Meerkat and Periscope, those discussions are literally folded into the event being observed. The conversation becomes indistinct from its topic.

It’s not shocking that the live feeds of the aftermath of the Manhattan explosion generated an almost immediate flurry of speculation about the future of reporting. In the Verge, Ben Popper wrote that he was able to watch footage of the event within seconds. Almost breathlessly, he proposed that we were seeing a new form of “media consumption and creation” emerging, a rushed claim that some criticized as callous in light of the injuries caused by the explosion. Williams, in Next Web, echoed Popper’s pronouncement: “Periscope has begun to transform the way that news can be accessed and consumed overnight.”

As Williams also acknowledged, however, it may be difficult to get that news, especially if you don’t follow the right people on Twitter. In the wake of the explosion, I found myself struggling to find a live feed. Most of those I came across had already gone dark by the time I clicked through. Eventually I settled on two: One was a stable image filmed from a window high above the scene that showed little more than a plume of chalky smoke drifting above the city, almost like a papal signal. The other was a street-level video shot at the edge of zone cordoned off by the first responders and released through Mashable’s Twitter account.

Mashable’s videographer, who was streaming through Periscope with one hand and Meerkat with the other, did her best to gather information and relay it back to her viewers, but there was little information to be found. At one point, a police officer stopped her, asking, “Is there a reason you’re recording this? Are you with the press?” She hesitated only a moment before responding, monosyllabically, “Yes.” Telling her that she should have identified herself, he declined to comment further.

In both apps, the steady march of comments across the image seemed to provide more information than the video stream. Some of it was factual, derived from Mayor Bill de Blasio’s news conference or other official sources. “Nyc gas explosion 12 hurt,” one viewer explained. Other information felt more conjectural, as in the case of a Periscope commenter who wrote, “That’s not normal smoke there. It’s poison.” Mashable’s reporter seemed to be getting most of her facts from these comments, much as more traditional television anchors might from the producers speaking through their earpieces. This confusion between presenter and audience is clearly troubling, not least of all because it empowers gossip and confusion.

Footage of the event, then, was ultimately more a backdrop for news than it was a source of news itself. Many of the commenters on these streams weren’t even talking about the explosion and its aftermath. Instead, they were arguing about which app had the better image quality, or proclaiming, even more emphatically than the Verge or Next Web, “THIS is the future of news.” But was it? As Popper acknowledged of his own earlier viewing, “I had less information than I would if I had waited for a formal news crew to arrive, report out what was happening, and then pass that information back to me.”

Visually, neither of the streams I watched provided anything truly insightful. The aerial one might as well have been a still image. It was too far from the scene to reveal more than the fact that the fire was still burning. Mashable’s stream, by contrast, was too close to the event to offer any real perspective. People weren’t getting information from either that they couldn’t have found more easily and more clearly on Twitter—or by reading news reports or flicking on the TV news.

If these apps had anything to offer, it wasn’t information about the tragedy; it was the feeling of participation in it. Many of the commenters engaged with the streams—especially with Mashable’s—as if they were there on the scene, as if Mashable’s videographer were a proxy for their own presence. At least so far, Meerkat and Periscope may put us in the moment, but they’re no more useful than any of the tools we already have. They let us feel as if we’re involved in something, but they don’t necessarily tell us much we don’t know. In the process, they remind us that being there, being in the thick of things as they unfold, is often much more confusing than being elsewhere. This may change as the apps develop and as broadcasters learn to use them. For now, Meerkat and Periscope can show us what’s new, but that doesn’t mean that they show us the news.