Last Thursday night, the Wall Street Journal revealed that in 2012, Federal Trade Commission investigators had concluded that Google had unlawfully “used anticompetitive tactics and abused its monopoly power.” On the Web, fingers wagged over Google’s apparent violation of its old “Don’t be evil” credo; by using its search engine to boost its other businesses, Google had harmed its competitors, the FTC alleged.

We have heard this story before. The FTC had already told it to us, in somewhat nicer terms, in January 2013, when it announced a settlement with Google. While the previously secret report generally lines up with what the FTC said in 2013, it does raise some new questions. When the FTC announced its Google settlement over complaints brought by Microsoft, eBay, Yelp, and others, was it going against its staff’s recommendations? Did the concessions Google made address the FTC’s concerns? Did the FTC publicly misrepresent its own investigation? Are the loudest Google critics, like original complainants Microsoft and Yelp, just expressing sour grapes, or did the FTC cave on real anti-competition issues? A close look at the report and the Journal’s coverage reveals no bombshells, but a few new wrinkles. If you care about fostering competition on the Web, the findings are cause for both comfort and concern.

The Journal identified four issues over which the FTC found evidence of anti-competitive business practices by Google. (Disclosure: I used to work for Google and Microsoft, and my wife still works for Google. I did not work on anything related to these four issues.) Only with one is there a substantive difference between the FTC staff report and the FTC’s previous public statements. This is the “exclusive agreements” issue, dealing with Google’s contractual restrictions on companies like Amazon that syndicated Google’s search results. While one FTC commissioner publicly wrote that there was no evidence of coercion because “virtually none of Google’s partners are seeking to switch any of their business to non-Google providers”—an assertion the report backs—the report nevertheless claims to have found Google’s contracts unlawful, if resulting in “only modest anticompetitive effects.” The report recommends a remedy for this issue on Page 113; unfortunately, only the even-numbered pages of the report were accidentally released to the Journal. While this issue is less major than the other three issues, the FTC should still clarify its official stance on exclusive agreements and why it apparently chose not to pursue a remedy.

When it comes to new stuff, though, that’s about it. University of Maryland professor and Internet law expert James Grimmelmann, author of “The Google Dilemma,” found little surprising in the report: “It focused on exactly the same issues—search bias, vertical search, and ad campaign portability—that were widely debated in public during the investigation.” Broadly speaking, the remaining three issues line up with what the FTC publicly reported about its settlement with Google in January 2013, and, indeed, what the Journal itself reported on the settlement at the time. The rhetoric is harsher, but the substance is basically the same. Google made concessions to the FTC on two issues. First, it allowed advertisers to optimize campaigns across multiple ad networks simultaneously by removing restrictions on the use of its AdWords API. Second, Google allowed websites to opt out of being used in Google’s vertical offerings such as Google News and Google Flights. A company like Yelp originally had no choice but to let Google use its data in those verticals; its only other option was to not be included in Google search results at all. The FTC objected to this “all-or-nothing choice” and forced Google to allow Yelp to pull its data from Google’s verticals without penalty. This is, indeed, precisely the remedy recommended by the staff report.

Screenshot via Google

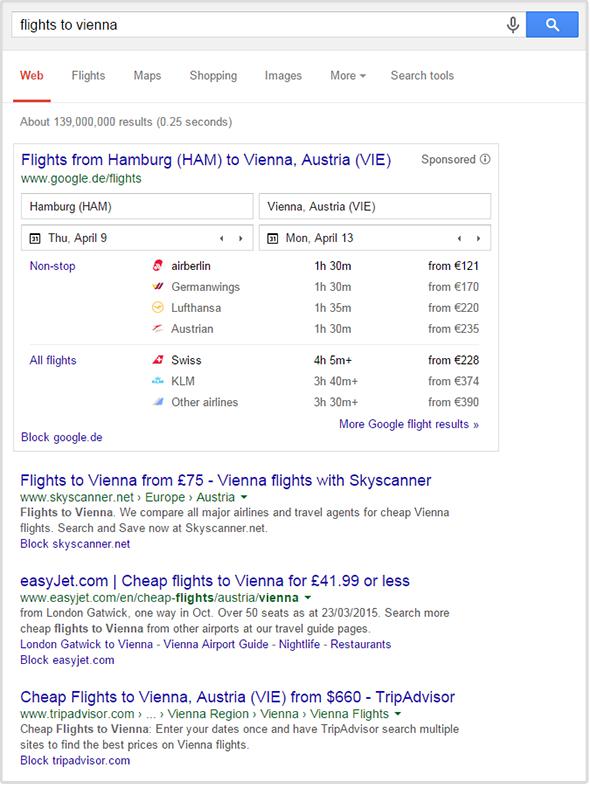

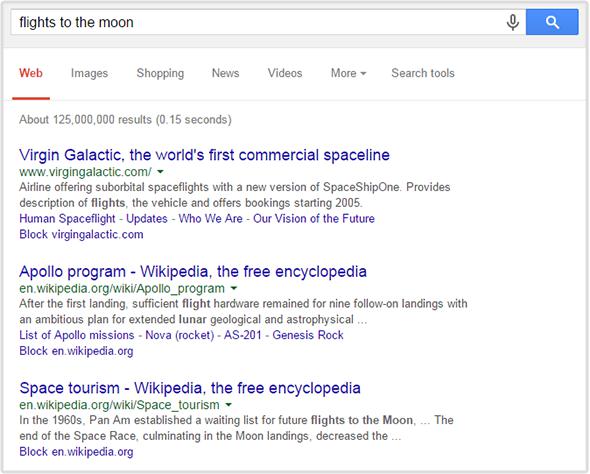

That leaves what is by far the biggest issue: the promoting and demoting of search results to privilege Google’s business. The so-called search bias issue that the FTC investigated relates primarily to “Universal Search” or “OneBox,” in which Google prominently blends its vertical offerings into its plain vanilla search results. Originally rolled out in 2007, Universal Search doesn’t play into every search, but it makes its presence known frequently enough. The main charge against Google was that it was abusing its power as the pre-eminent search engine by unfairly promoting its own vertical offerings at the expense of competitor sites that would show up in the vanilla search results, since the verticals would sometimes appear at the top of the page, above the other results, if Google deemed its own vertical content to be “highly relevant” to the search. On this issue of search bias, Google did not make concessions, and the FTC did not take action (nor does the staff report recommend action, though it says it’s a “close call”). It’s not an exaggeration to say this issue gets at the heart of Google’s search engine: To what extent can Google push its own aggregated content into its searches, if these offerings are in competition with businesses that show up in the search results? Is the result merely an improved Google “search,” or is it plainly anti-competitive?

Screenshot via Google

Because Google is the ultimate arbiter of the results it displays—and because its “relevance”-ranking algorithms are more or less a black box to anyone outside the company (and many within it)—Google’s responsibility has to be what the company itself has said many times: to provide the best search results for the user rather than search results that might privilege its business. The fact that these two goals aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive is where the difficulty comes in. Google has repeatedly said that any changes it makes to its search engine are to benefit the consumer, even if they happen to harm Google’s competitors, and the FTC reports that Google made this argument to its investigators as well. Alongside a long list of “litigation risks,” the report notes that U.S. courts have tended to accept this argument, perhaps explaining why the FTC sought a settlement. The question—as Grimmelmann put it in the article “What to Do About Google?”—is whether Google was acting in bad faith, fiddling with its search results with the ulterior motive of harming its competitors.

One example from the FTC report shows how hazy the line can be. When testing changes to its ranking algorithm, Google has “raters” manually assess different sets of search results for the same query and rate which one is better. In one such experiment, Google tried demoting “comparison shopping websites” like NexTag to see if its raters liked the results better. When they didn’t, Google tweaked the demotion algorithm until they did. These experiments were not, according to the report, conducted in connection with the promotion of Google’s OneBox results, so Google did not appear to be rigging the experiments to the explicit benefit of its verticals.

Yet what if such a rating-driven demotion happened to benefit Google’s verticals at a cost to competitors? By the FTC’s standard, that would seem to be OK, as long as users preferred the results anyway. And Google apparently made a strong enough case that the OneBox results were an honest attempt to benefit consumers. “If Google had been sabotaging its results in ways that made them less relevant to users,” Grimmelmann says, “that might have been more explosive, but it doesn’t appear that the FTC found that kind of evidence.” Again, the report matches up with the FTC’s public conclusions in 2013 and its decision not to sue or get a settlement on the big issue of search bias: “Google took aggressive actions to gain advantage over rival search providers,” the FTC’s outside counsel said in 2013. “However, the FTC’s mission is to protect competition, and not individual competitors. The evidence did not demonstrate that Google’s actions in this area stifled competition in violation of U.S. law.”

You can see, however, why Yelp, TripAdvisor, and others originally complained to the FTC: If Google privileged its verticals in its results over your own sites, you’d want to be sure no fishy business was going on. Because Google is measuring its ranking algorithms with its own secret yardstick (that is, its raters), there is a good case for some investigation of its methods to assure that they are being performed in good faith. They apparently are, at least according to the FTC. And the released half of the report does not suggest either a cover-up by the FTC or excessive lassitude on its part. If you thought its decision was acceptable in 2013, there’s not much in the released sections of the report that will sway your mind. If you didn’t like it, the Journal’s analysis gives little reason to like it any less. The report does, however, serve as good justification for the FTC sticking its nose into Google’s business, and the antagonistic tone of the report is refreshing compared to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s frequently hands-off attitude toward banks.

Because of my prior associations with Google and Microsoft, I’ve attempted to stick to the substance of the report rather than passing judgment on Google. Broadly speaking, however, I tend to agree with Search Engine Land’s Danny Sullivan when he says that Google’s Android mobile platform is of significantly greater concern than Google’s search engine. (Google Plus also would also have been a concern had it not utterly failed, since it locks users into a social network and user account.) Consumers are bolted into the Android platform to a far greater extent than they are to a search engine, and Ron Amadeo’s report in Ars Technica on the increasingly closed nature of the Android platform points at some real problems.

Barring major surprises in the unreleased sections of the report, I do not see much new that will affect Google going forward. The biggest claim—that of search bias—is also the one where the FTC appears to have found the least to act on and little grounds for renewed action, at least in this country. (Meanwhile, the European Union continues its four-years-and-running antitrust probe of Google.) Grimmelmann says the FTC’s ultimate decision still makes sense in light of the report: “The FTC will almost always take a negotiated outcome when they can get one instead of suing, whether it’s a two-bit spyware vendor or the biggest search company in the world. All in all, it looks like everyone at the FTC basically did their job.” That may not satisfy Yelp or Microsoft, but even according to the staff report, the FTC didn’t think it could do much better.