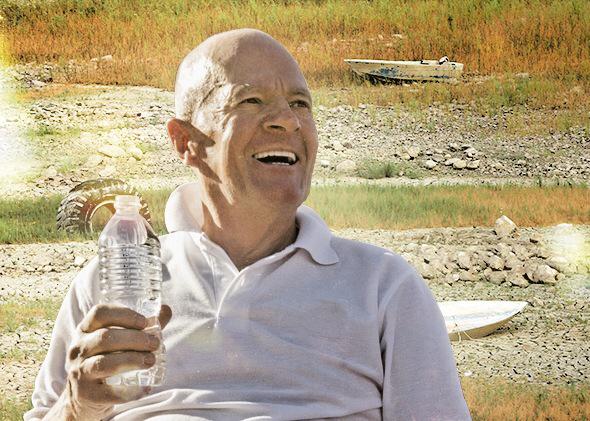

Las Vegas is parched. A 14-year drought has left Lake Mead, the local water source, dangerously low. It has dropped 100 feet in the past decade. If it drops 12 more feet, federal water rationing rules will kick in. Some climate scientists predict that will happen in the next year. And most believe the situation will only worsen over time.

The view from inside Las Vegas’ Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino, however, is considerably rosier. That’s where scientists, activists, and bloggers have assembled this week for the Heartland Institute’s 9th International Conference on Climate Change, which I’ve been following via live stream. It’s the world’s largest gathering of “climate skeptics”—people who believe, for one reason or another, that the climate change crisis is overblown.

It’s tempting to find irony in the spectacle of hundreds of climate change deniers staging their convention amid a drought of historic proportions. But, as the conference organizers are quick to tell you, they aren’t actually climate change deniers. The majority of this year’s speakers readily acknowledge that the climate is changing. Some will even concede that human emissions are playing a role. They just think the solutions are likely to be far worse than the problem.

“I don’t think anybody in this room denies climate change,” the Heartland Institute’s James M. Taylor said in his opening remarks Monday. “We recognize it, but we’re looking more at the causes, and more importantly, the consequences.” Those consequences, Taylor and his colleagues are convinced, are unlikely to be catastrophic—and they might even turn out to be beneficial.

Don’t call them climate deniers. Call them climate optimists.

They aren’t an entirely new phenomenon. Fossil-fuel advocates have been touting the advantages of climate change since at least 1992, when the Western Fuels Association put out a pro–global warming video called “The Greening of Planet Earth.” (It was a big hit with key figures in the George W. Bush administration.) Naomi Oreskes, co-author of Merchants of Doubt, traces this line of thinking even further back, to a 1983 report in which physicist Bill Nierenberg argued that humans would have no trouble adapting to a warmer world.

As global warming became more politically polarized, however, coal lobbyists and their shills largely discarded the “global warming is good” approach in favor of questioning the science behind climate change models. These days the liberal stereotype of the climate change denier sounds more like James Inhofe, the Republican senator from Oklahoma who dismisses “the global warming thing” as “the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people.” (He still appears to believe that.)

There are still a good number of Inhofe types at the Heartland Institute’s conferences. But the pendulum of conservative sentiment may be swinging away from such conspiracy theories. Over the past few years, a concerted campaign by climate scientists and environmentalists, backed by mountains of evidence, has largely succeeded in branding climate change denial as “anti-science” and pushing it to the margins of public discourse. Leading news outlets no longer feel compelled to “balance” every climate change story with quotes from cranks who don’t believe in it. Last month, the president of the United States mocked climate deniers as a “radical fringe” that might as well believe the moon is “made of cheese.”

The backlash to the anti-science movement has left Republican leaders unsure of their ground. As Jonathan Chait pointed out in New York magazine, their default response to climate change questions has become, “I’m not a scientist.”

It’s a clever stalling tactic, allowing the speaker to convey respect for science without accepting the scientific consensus. But it’s also a cop-out, and it seems unlikely either to appease the right-wing base or to persuade the majority of Americans who have no trouble believing that the climate is changing despite not being scientists themselves. At last count, 57 percent told Gallup they believe human activities are to blame for rising global temperatures. That’s up from a low of 50 percent in 2010.

Eventually, then, top Republicans are going to need a stronger answer. And they might find it in the pro-science, anti-alarmist rhetoric exemplified by the climate optimists. Those include Richard Lindzen, the ex-MIT meteorology professor who spoke at the institute’s 2009 conference and is now a fellow at the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute.

In a 2012 New York Times profile, Lindzen affirmed that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas and called those who dispute the point “nutty.” But he predicts that negative feedback loops in the atmosphere will counteract its warming effects. The climate, he insists, is less sensitive to human emissions than environmentalists fear.

Fellow climate scientists have found serious flaws in his work. Yet it retains currency at events such as the Heartland conference, where skeptics’ findings tend not to be subjected to much skepticism themselves. (While several of the speakers are in fact scientists, few are climate scientists, and their diverse academic backgrounds make it difficult for them to engage directly with one another’s research methods.)

And the idea that the Earth’s climate is too powerful a system for us puny humans to upset holds a certain folksy—not to mention religious—appeal. Still, the Heartland crowd is careful to frame its arguments in terms of science and skepticism rather than dogma.

The climate-optimist cause has been aided immeasurably by a recent slowdown in the rise of the Earth’s average surface temperatures. There are several potential explanations for the apparent “pause,” and most climate scientists anticipate that it will be short-lived. But it has been a godsend for those looking for holes in the prevailing models of catastrophic future warming.

“Skeptics believe what they see,” said Heartland Institute President Joseph Bast. “They look at the data and see no warming for 17 years, no increase in storms, no increase in the rate of sea-level rise, no new extinctions attributable to climate change—in short, no climate crisis.”

Meanwhile, the optimists point out, more carbon in the atmosphere means greater plant productivity and new opportunities for agriculture. In fact, Heartland communications director Jim Lakely told me in a phone interview, “The net benefits of warming are going to far outweigh any negative effects.” Indeed, the institute recently published a study arguing just that.

The climate-optimist credo aligns neatly with public-opinion polls that show most Americans believe climate change is real and humans are causing it—they just don’t view it as a top priority compared with more tangible problems like health care costs. You can imagine how eager they are to be reassured that their complacency won’t be punished.

Again, not everyone at the Heartland conference is a climate optimist. Many are still focused on disputing the basic link between atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and global temperatures. As I watched the conference, it became clear that some have little trouble flipping between the two viewpoints. “This is what they always do,” Oreskes told me in an email. “As the debate shifts, they shift.”

That makes it easy for liberals to dismiss self-professed climate skeptics as industry shills in scientists’ clothing, especially since many of them, like the Cato Institute’s Patrick Michaels, do in fact receive funding from the fossil-fuel industry. For their part, the Heartland academics tend to view most mainstream climate scientists as conflicted by their reliance on government grants.

In fact, it’s not unreasonable to see the climate fight as part of a much broader ideological war in American society, says Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. The debate over causes is often a proxy for a debate over solutions, which are likely to require global cooperation and government intervention in people’s lives. Leiserowitz’s research shows that climate deniers tend to be committed to values like individualism and small government while those most concerned about climate change are more likely to hold egalitarian and community-oriented political views.

That doesn’t mean, of course, that the evidence on both sides is equal. There’s a reason the climate deniers are losing the scientific debate, and it isn’t because academia is better funded than the energy industry. All of which helps to explain how climate optimism might be a more appealing approach these days than climate denial. Models of how climate change will impact society and the economy are subject to far more uncertainty than the science that links greenhouse gas emissions to the 20th-century warming trend. The costs of mitigating those emissions are more readily grasped: higher energy bills, government spending on alternative energy projects, lost jobs at coal plants.

There are, however, a few pitfalls for conservatives who would embrace climate optimism as an alternative to climate change denial. Touting the recent slowdown in global average surface temperatures, for example, implies that such temperatures do in fact tell us a lot about the health of the climate. That will become an awkward stance in a hurry if the temperatures soon resume their climb.

More broadly, shifting the climate change debate from causes to outcomes will put the “skeptics” in the Panglossian position of continually downplaying the costs of extreme weather events—like, say, the Las Vegas drought—even as their constituents are suffering from them. In the Heartland conference’s opening keynote speech, meteorologist Joe Bastardi scoffed at the devastating wildfires that have swept across the Southwest far earlier than usual this season. “We had the wildfires in San Diego, right?” he said in a derisive tone. “I think it destroyed 80 houses, 90 houses. They had a wildfire back in October 2007 that took out 1,500 houses. … When people tell me things are worse now, I say, ‘You can’t be looking at what has happened before.’ ”

It’s one thing to tell people global warming isn’t the source of their misery. It’s a lot harder to look them in the eye and tell them their problems aren’t that bad—especially if you’re relying on them to vote you into public office.