There are two problems with smartphones.

One is that they’re distracting. To use one, you have to pull it out of your pocket, hold it in your hand, and look away from the world around you.

The second problem is that they’re small. The keys are tiny, making typing difficult, and Web pages don’t always adapt well to 4-inch screens.

To these problems, the technology industry has offered a solution: wearable gadgets. Google Glass in particular has been touted as a more seamless way to experience the digital world: no more peering down at a handheld gadget to get directions, no more fiddling with a miniature touchscreen keyboard. With smart glasses, you just glance upward to see the screen; commands are carried out by voice, or with a simple tap or swipe of the frame.

That’s the theory. Here’s my experience: In most cases, smart glasses are more distracting than smartphones. Their screens are smaller, too. Oh, and you still need a smartphone in order for them to work when you don’t have Wi-Fi. Smartphone problems: unsolved.

An example of smart glasses’ unfulfilled promise is an app called Field Trip, which Google promoted at a media event at New York City’s Chelsea Market on Thursday. The event was meant to show how Glass can be a handy tool for the tourist on the go. But, as with my first trial of Field Trip on Glass several weeks earlier, I came away convinced you’d be better off leaving home without it.

The Field Trip concept, developed by Google’s own Niantic Labs, is intriguing: Speak the words “OK Glass, explore nearby” and the device’s screen will display a series of cards devoted to notable sights in your immediate vicinity. You can search by category—food, architecture, history—or just browse at random if you’re feeling lucky.

The results, however, amount to a frustrating lesson in the limitations of a device that’s too small to deliver the full power of the open Web. “Explore nearby,” I commanded my glasses. The first card that popped up bore the cryptic title, “SL – Architizer.” I tapped the glasses’ frames to learn more, and was treated to some photos of what appeared to be a swanky nightclub. I eventually discerned that SL was the club’s name and Architizer the name of the content source, but I still didn’t know where SL was, nor why I should care.

“Get directions,” I said. Glass commenced a Google Maps search—and promptly froze. Eventually I had to turn off the device and reboot it. I tried again, and this time Maps pinpointed a location a block or two away. Moments later, it changed its mind. “You have arrived!” it announced cheerfully.

On my second try, I searched for food and up popped an article about an establishment called the Doughnuttery from a site called Tasting Table. “The Doughnuttery makes pint-sized donuts,” it informed me. “No doubt you are being bombarded with diet ideas for 2013.” I was not being bombarded with diet ideas for 2013, nor did these nonexistent diet ideas involve miniature donuts, but I pressed on. This time, I left the Field Trip app to seek directions via Glass’ standard Google search function. Unfortunately, the device heard “Donuttery” and pointed me to a place in Huntington Beach, California, that makes regular-sized (!?!) donuts. With Glass’ limited interactivity, I saw no obvious way to correct the error. And I never even wanted any doughnuts!

To be fair, Field Trip’s suggestions can occasionally be as serendipitously pleasing as you might hope. A history search turned up a well-written article about the history of the High Line, the abandoned elevated rail line that has been turned into a distinctive public park. I hadn’t realized that former mayor Rudy Giuliani had been planning to demolish the line before a pair of grassroots preservations dreamed up the park idea.

Yet as I gazed upward and to my right, upward and to my right, to read a sentence or two at a time on the tiny screen, I found myself wishing that I could just read the article on my smartphone’s Field Trip app instead. I was no less distracted reading it on Glass, but the process was slower and less comfortable and I looked twice as silly.

The effect is magnified on a busy street, where you’re tempted to keep walking while using Glass. Unless everything goes right—which is rare, in my experience—you end up having to repeat voice commands and swipe repeatedly to back up and toggle through results, all while glancing nervously back and forth between the screen and the sidewalk in front of you. You’d almost certainly be safer just stepping out of everyone’s way, using your smartphone for a minute, and then putting it back in your pocket so you can return your focus to the world around you.

(An observation: When I’m without my smartphone for some reason, I feel anxious and incomplete until it’s safely back on my person. With Glass, it’s the opposite: Whenever I’m using it, I feel anxious and distracted until I take it off.)

Tripit, an on-the-go travel app, makes a slightly better case for Glass’ utility, if only because the airport is one place where you’re likely to have both hands full of luggage. You can use it to double-check your rental car reservation or get an alert about a gate change for your flight without breaking stride (provided you don’t trip over anyone else’s bags while you’re glancing up at the screen). Again, though, there are bugs to be worked out, and you can only do so much with it before you have to dig out your phone. For instance, if your flight is late, there’s an option to see a list of alternate flights to your destination. But you can’t select any of them, or call to change your reservation: They’re just displayed on a static card.

Google Glass isn’t bad at everything. It’s a great improvement over smartphones for a few specific purposes, like snapping a photo on the fly or shooting video while your hands are occupied. It can also be helpful in its capacity as a heads-up display—e.g., for glancing up at a recipe while you’re cooking.

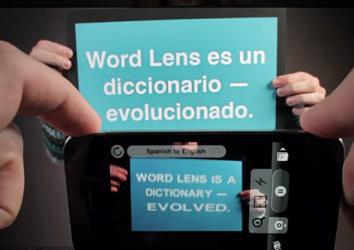

And one app that Google showed off on Thursday looks genuinely great. It’s called Word Lens, and it’s the niftiest translation tool I’ve yet encountered. Say you find yourself on a street in Russia staring at a sign that you can’t understand because you don’t speak Russian. Open Word Lens, select “Russian to English,” and then look at the sign again. As if by magic, Word Lens replaces the Russian words with their English counterparts right before your eyes.

The translations aren’t perfect. They’re actually just one-to-one transliterations, and the mistakes can be comical. Presented with a sign that read “Joyeria del Barrio,” it tried “Jewelry of Mud” and “Jewelry of Barrel” before (mostly) correctly settling on “Jewelry of Neighborhood.” But surely they’ll continue to improve. And while Word Lens has been available on smartphones for a few years now, it’s the rare app that works significantly better on Glass, because you can just look at the word you want to translate instead of having to aim a camera and read a screen.

Apparently it isn’t lost on Google that Word Lens is a potential killer app: Google announced on Friday that it’s buying Quest Visual, the startup that makes it.

Screenshot via QuestVisual/YouTube

It’s a reminder that, as underwhelming as Glass might be today, the technology is still in its infancy. Google—and the rest of us—are still just beginning to figure out what smart glasses can and cannot do. Glass is likely to be judged harshly upon its release, thanks in part to the high bar that Apple and other consumer-electronics companies have set for mobile devices over the past decade. As a replacement for—or even a supplement to—a smartphone, smart glasses today simply aren’t worth the trouble, let alone the price.

Still, let’s give Google and its rivals a few years before we give up on smart glasses. In the meantime, maybe we can start appreciating our smartphones a little more. As distracting as they can be, at least they still spend most of their time hidden away in our pockets.