I’m not typing this article. I’m dictating it to my iPhone as I walk down the busy city street on the way to my office in the West Village.

Admittedly the iPhone’s speech-recognition features went [sic] meant for composing full-length articles for publication. Sorry, that should have been “weren’t.” Some transcription errors are inevitable, but I’m doing this to make a point. Our mobile devices have gotten surprisingly good at understanding us—probably a lot better than you remember, if you haven’t tried talking to your phone in a while.

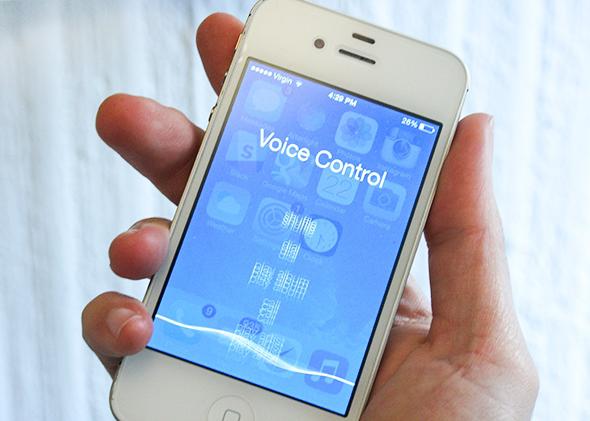

Speech recognition technology got a lot of hype around the time that Apple first released Siri, four years ago this week. But if you’re like most iPhone users, you soon just missed the haunted voice assistant as little more than a parlor trick. (Sorry that was supposed to be “dismissed” not “just missed.” And “vaunted” not “haunted.”) Series frequent misunderstandings—whoops, I mean Siri is a frequent misunderstandings—darn it, I mean the frequent misunderstandings by Siri – gave it more comedic value than practical value.

Believe it or not, despite the voice typos above, that’s no longer the case. Not only is Siri a better listener than it used to be, but Apple’s notes and mail apps have sprouted serviceable dictation features, too. And as much as Apple’s speech- recognition capabilities have improved, the ones Google has added to its mobile apps and android operating system may be even better. In both cases, typing by voice is now easier in many cases than doing it by touchscreen, especially if you’re on the go. And on the coming wave of wearable devices, like Google Glass, voice commands are replacing typing altogether. Meanwhile, Amazon’s big pitch for its new set-top TV box, Amazon fire TV, is that it’s voice recognition features actually work – even for Gary Buse. That’s “its.” And “Gary Busey.”

Clearly the technology is not yet perfect. How men’s are still problematic, for one thing. I mean homonyms are still problematic, although Google in particular has gotten quite good at discerning your meaning from the context. And if you want punctuation marks, you have to speak them out loud. Like, you have to say the word. If you want to end a sentence. Sorry, I mean you have to say the word “period” if you want to end a sentence.

I’m going to go back to typing on my laptop now, both because I need my notes and because I’m sure both you and my editor are tired of the typos. [I’m totally fine! —Ed.] And to be honest, I was starting to feel a little like Joaquin Phoenix in Her, murmuring sweet nothings to my mobile device as I moseyed down Hudson Street.

Still, I wouldn’t have dreamed of trying to compose even a brief work-related email on a smartphone by voice just a couple of years ago, let alone a full-length Slate column. Now I do the former on a regular basis. And for some basic tasks, like placing a call to someone in my address book or typing up a grocery list, I almost never use the keypad anymore unless I’m forced to. Which reminds me of one other obstacle: Talking to your mobile device typically requires an Internet connection.

Speech recognition software’s reliance on the cloud is both an inconvenience and the source of its power. You’ll notice that when you dictate something, there’s a brief lag before it shows up on the screen. That’s because your device is zipping your voice signals to remote servers for processing and interpretation before it can transcribe them.

One reason Google’s technology has improved so rapidly, explains engineering director Scott Huffman, is that all that incoming voice data gives the company’s machine-learning algorithms a lot to work with. Another is that the algorithms themselves have gotten more powerful. “One of the big advances over the last year or two,” he says, “has been in using new kinds of machine-learning technology that are scaled to many, many machines. We call it deep neural networks, or deep learning. We’re now able to apply very large-scale parallel computing to interpret the sounds that you make.”

The software’s first job is to figure out which sounds are your words, as opposed to ambient noise or the words of people around you. For a nonhuman, that’s harder than you might think. Then it has to parse your speech by evaluating not only each sound you make, but also the linguistic context that surrounds it—just as people do subconsciously when they listen to one another.

Sometimes you can actually see the software recalibrating on the fly. Recently I told my Google app, “Remind me to email Ben at 4 o’clock.” At first I saw it type, “Remind me to email Bennett.” But when it heard the words “4 o’clock,” it realized I had more likely said “Ben at” then “Bennett,” and it duly set the proper reminder.

This is exactly the type of computing problem at which Google excels. The company’s core product, Web search, relies on its ability to intuit the intent behind a string of search terms, even if they’re misspelled or ambiguously phrased. A search for “bank” will turn up different results based on your location and search history. Similar smarts could soon be applied to the company’s speech recognition technology, Huffman said. When you’re in Boston, for instance, Google might be more likely to render “red socks” as “Red Sox,” especially if it knows you’re a baseball fan.

Apple won’t talk as much about its own speech recognition technology, but it’s clearly working hard to keep up. It built Siri with the help of a partnership with Nuance, the company behind the popular Dragon speech recognition software for PCs. More recently, it appears to have acquired another speech recognition company, called Novauris Technologies, which has worked on technology to process speech locally on your device rather than sending it to the cloud. That could help it keep pace with other rivals like Intel, which are hoping to leapfrog Google and Apple in speed by cutting the Internet out of the equation.

The smoother the technology gets, the less typing we’ll do on our smartphones. An informal poll of my colleagues turned up several who already use voice functions for a range of applications, from setting timers and alarms to settling a bet at a bar. When you’re out with friends, pulling out a phone and typing a query into Google feels antisocial, one colleague observed. But asking Google a question out loud and getting a spoken response “just feels like part of the conversation.”

And it isn’t just young, tech-savvy types who are doing it. Several people I talked to said it’s actually their parents who are using their phones’ voice features the most—because they’re the ones who most hate typing. “I had a Kasparov vs. Deep Blue–style race with my dad,” staff writer Forrest Wickman told me. “He uses [dictation] all the time and was convinced it was faster than typing by hand.” Wickman’s father lost—but I bet that within a year or two, he’ll win.