There’s a lot of news about Whisper, Secret, and other anonymous social networks lately. Whisper has been around in various forms since March 2012 but started gaining momentum when it went free in February, Yik Yak started late last year, and Secret went live in the App Store at the end of January. Together they have prompted soul-searching questions about how much weed the employees of Rap Genius smoke and whether or not Gwyneth Paltrow is having an affair. More importantly, their spike in popularity raises questions about security, cyberbullying, and harassment.

The real secret about all of these apps, though, is that they’re nothing new. They’re a repackaged version of the anonymous social channels that already existed on the Internet. What’s more—and you probably could have guessed this part—they’re not even secret.

The services use your smartphone’s location or contacts list to either find users in a set radius around you or to show you secrets from your friends list (anonymously, of course). You also see posts from a wider user pool, which are chosen by algorithms. The “secrets” are sometimes inspiring, but often veer toward criticism and shaming. In the months since Yik Yak launched, it has jumped from college campuses to high schools and middle schools, even though users are supposed to be 17 or older. And the service has played host to such extreme bullying in schools that the founders have already had to publicly address the situation.

“In a small handful of cases—probably three or four—we dealt with local authorities in terms of threats that have been issued on Yik Yak,” one of the founders, Brooks Buffington, told TechCrunch.. “A few of them actually resulted in arrests.” Yik Yak has also geofenced the locations of almost 130,000 schools nationwide, so students can’t use Yik Yak while they’re on campus.

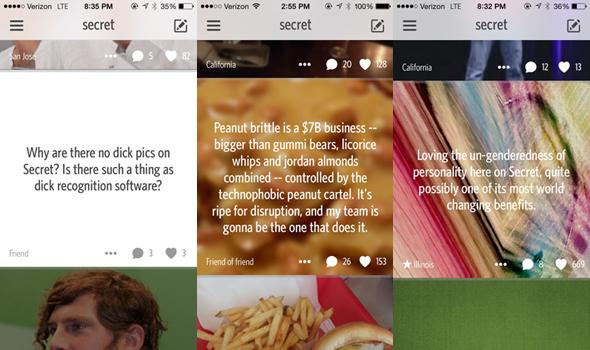

Over at Secret, posts have ranged from Silicon Valley gossip to poignant life observations and sad truths, from “I really hope the King IP is a flop. Their litigious practices against other game developers leading up to the IPO are atrocious” to “Today brings me one day closer to accepting myself as I am.” The company likes to highlight positive content that gets a lot of “hearts” (the equivalent of “likes” or “favorites”). But bullying has apparently cropped up on Secret, too. A recent example involved a female engineer, Julie Ann Horvath, who had quit her job at the open-source hosting company GitHub; Horvath had had problems with one of the GitHub founders and his wife, and also felt uncomfortable with what she perceived as a culture of sexism among the GitHub staff. She originally planned to leave the company quietly, but after people began posting nasty rumors about her on Secret—referring to her as “Queen”—she began speaking out publicly on Twitter and elsewhere.

These and other incidents have given anonymity apps a lot of visibility and made them seem almost novel. But while the apps have updated aesthetics and functionality for mobile, in reality they are simply the next generation of the anonymous forums that have existed online for years—a hybrid of the anonymous message boards at 4chan, the anonymous question-and-answer network at Ask.fm, and the anonymous confessions at PostSecret. 4chan and Ask.fm are both known for bullying and trolling; sometimes these situations get so intense that they spill from one site into the other. Apps like Secret are part of this culture now. The New York Times argues for a clear distinction between the new wave and the old wave: “Unlike older, Web-based message boards and forums, Secret posts are easy to pass around through text messages or on social media. All you need do is upload a screenshot to spread something meant for a few friends to dozens or even hundreds of people.” It is true that screenshots are easier to text from a mobile phone, but any anonymous post viewed on a desktop has been easy to screencap and share via email, instant message, or social media for years.

In thinking about how to curb bullying on these platforms, the instinct seems to be to devise new strategies, like Yik Yak’s school geofencing idea. And, of course, adapting to new circumstances is necessary. But because bullying is such a serious problem, it can be easy to lose context in the rush to come up with new protections. In a recent New York magazine piece, one technologist suggests using “strong cryptographic identity systems based on non-real identity” to make people more accountable for what they say in anonymous apps. The cryptographic identities would be similar to those in bitcoin, which allow you to track a bitcoin account’s transactions without knowing the identity of the human behind them. The idea is that bullies might be less harsh if there were some way of tracking their old comments and giving them an anonymous persona—but again, it’s the same solution that anonymous commenting systems and message boards have had for years: usernames. If you choose a username on Reddit, it doesn’t have to reference your actual name; people can track every comment you’ve ever made and develop a sense of your persona without knowing who you are.

Would cryptographic identities be better suited than usernames to anonymous social media because they’re more secure? The fact is that anonymous apps are not particularly secure in the first place. If revelations about NSA surveillance and the ensuing flood of “privacy” products has taught us anything, it’s that making something truly anonymous is really hard. If privacy protection is difficult to achieve for communications related to espionage or drug smuggling, it’s certainly not going to be infallible on consumer products meant for sharing non-state secrets.

Indeed, the idea that any of these apps are completely anonymous is dangerous. These companies know who you are and what you post. As Forbes points out, Whisper is open about the fact that it tracks users, and it’s also considering targeted advertising.

In its FAQs, Secret says, “All of your posts are encrypted such that nobody, especially our team, can see your content. Your secrets are safe with us.” But what would happen if Secret were subpoenaed for the identity behind a post? Secret says that it “may share information about you … in response to a request for information if we believe disclosure is in accordance with any applicable law, regulation or legal process.” And Whisper has an entire “Law Enforcement Response Guide” that outlines the company’s criteria for identifying the author of a post to law enforcement agents. Basically it’s the same standard setup that anonymous posting services have had for years.

Anonymous message boards at colleges are still rife with bullying and harassment. That type of forum didn’t die in the early 2000s—it has just been repackaged over and over again, and the older anonymous channels are still alive and well alongside the new breed. Like their predecessors, anonymous apps may produce some interesting discourse. But by and large, we’ve known for a long time how humans act when given the appearance of digital anonymity.