One day last week, Christine Fox came across a news article about an unidentified sixtysomething woman who had been raped by her grandson. Fox has amassed a modest following on Twitter, and she was moved to share the story with the flock.* She tweeted the link to her 13,000 followers and, in a sly commentary on a culture that routinely blames sexual assault victims for the attacks against them, added: “I wonder what she had on to entice him.”

Then, Fox asked survivors about the clothes they were wearing when they were assaulted. They came back with items including “pink princess pajamas,” “roller skates,” and “T-shirt and jeans,” each nodding to Fox that the information was OK to retweet. She did, and her feed converted into a rolling real-time rebuke of victim-blaming. Within hours, the story blew up, skipped out of Fox’s feed, and turned into grist for the Internet news cycle.

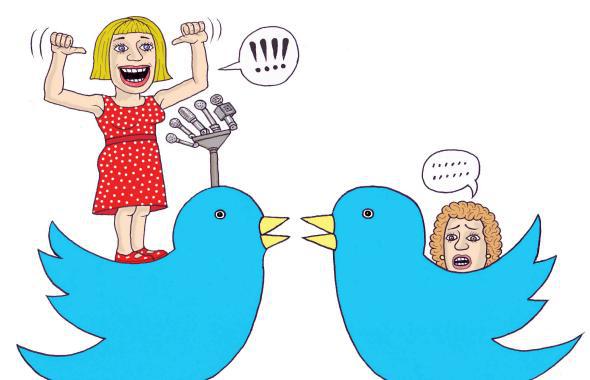

First, BuzzFeed, which attracts 150 million unique visitors a month, picked up the conversation and republished Fox’s tweets on its own platform. Then, readers shared the story across Facebook, sending Fox’s picture and Twitter handle—which had been automatically embedded into the coverage along with her tweets—to thousands more. Far-flung friends and family contacted her about her unexpected fame. “All of a sudden, my face became the face of rape survivors on the Internet,” Fox says. “I did not consent to that.”

What had started as a story about consenting to sex had turned into a story about consenting to viral news. BuzzFeed reporter Jessica Testa, who has proved herself committed to raising awareness about sexual assault issues, had asked the rape survivors for permission to republish their tweets, but she hadn’t asked Fox to use her handle and image to anchor the story. On Twitter, Fox pushed back against BuzzFeed’s amplification of her image without her OK; while some Twitter users backed Fox, media reporters defended journalists’ right to report on the news Fox had created, whether she liked it or not. Poynter ethicist Kelly McBride decided that while BuzzFeed was right to obtain the permission of assault survivors it quoted—respecting a long-standing tradition of news outlets not identifying rape victims without their consent—it wasn’t required to ask Fox, too. (Poynter later updated its story to note that Fox herself had identified as a survivor in the course of the Twitter conversation, though Testa didn’t identify her as such; supporters of Fox have signed a petition asking BuzzFeed and Poynter to retract their stories.) And in a hilarious essay on Gawker, Hamilton Nolan issued a “gentle reminder” that “Twitter is public.” A sampling:

The things you write on Twitter are public. They are published on the world wide web. They can be read almost instantly by anyone with an internet connection on the planet Earth. … Because Twitter is public, and published on the internet, it is possible that someone will quote something that you said on Twitter in a news story. This is something that you implicitly accept by publishing something on Twitter, which is public.

Yes, Twitter is public. But that’s a sentence that would have been entirely meaningless just 10 years ago. Journalists haven’t fully grappled with exactly what it means. Reporters interested in public opinion used to have to actually go outside, meet people—or at least call them on the phone—and identify themselves as journalists. Now, Twitter connects us to 230 million active users who publish a combined 500 million tweets every single day, giving us a direct line to random acts of advocacy and casual expressions of bigotry. The new, virtual man on the street doesn’t even need to be aware of a reporter’s existence in order to turn up on a highly trafficked news source with name, photo, and social media contact information embedded. It’s the journalist’s “right” to reproduce these public statements, sure. But our rights are expanding radically, while our responsibilities to our sources are becoming more and more optional.

The journalistic landscape has changed so much in such a short period that it feels a little square to harken back to traditional ethics codes. The Society of Professional Journalists’ version, which was established in 1926 and updated most recently in 1996, instructs journalists to “use special sensitivity when dealing with children and inexperienced sources or subjects” and to “recognize that private people have a greater right to control information about themselves than do public officials and others who seek power, influence or attention.” If reporters view all statements on Twitter as equally quotable—who among billions of Twitter users couldn’t be accused of seeking “attention”?—then the divide between public and private is rendered meaningless. On the one hand, news is being created and shared on social media, and journalists cover those platforms like a beat in order to keep their readers informed. On the other hand, the obliteration of the private sphere is very convenient for journalists, and not just because it enables us to exercise the right to a free press in service of the public good. Social media sourcing also allows journalists to push out a high volume of stories at a breakneck speed, racking up ad impressions along the way.

This is not just a BuzzFeed problem, or just a sexual assault reporting problem. In 2012 Jezebel searched Twitter for teenagers hurling racist epithets in the wake of Obama’s re-election—mostly to just a handful of other users—then notified school administrators about the slurs. Publicly shaming random teens who use social media to complain about their expensive gifts has become a new holiday tradition. I’ve sourced from Twitter in an attempt to register public opinion about news stories countless times. Sometimes, these random social media musings are clearly newsworthy, as when Boston bombing suspect Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s classmates unsuspectingly shared details about the fugitive in the wake of the tragedy. But other times it’s less clear, as when online journalists blasted a minor public relations official who tweeted one terrible AIDS joke; she ended up fired from her job and stalked in person.

In the past week, the disconnect between BuzzFeed’s rights and Fox’s expectations has inspired some journalists to begin to revisit their standards. When I talked with a handful of journalists about how they make decisions when sourcing from Twitter, they suggested that standards shift based on who’s talking, how many people listen to them, and what they’re saying. “It’s one of those things where you know it when you see it,” freelance writer and editor Anna Holmes told me. “There are no rules,” says Shani O. Hilton, BuzzFeed deputy editor-in-chief. “We’re all trying to figure it out.”

Twitter is a vast platform with members ranging from middle school students with five followers to the Twitter-verified Justin Bieber, who enjoys an audience of 50.4 million. For some reporters, taking a look at a source’s follower list can provide some indication as to how far they may expect their words to spread. “Most people on Twitter don’t have very many people following them. They’re not using it as a brand-building exercise; they’re using it at a social network,” Yahoo News Washington Editor Garance Franke-Ruta told me. “If someone is engaging in a very revelatory or confessional conversation that they’re broadcasting to just a couple hundred people, we can assume that they think they’re having a discreet conversation within a small community.”

To Franke-Ruta, those considerations don’t necessarily affect standards for what’s on or off the record. “It’s obviously on the record, but if we’re going to put that person in a story, we ought to consider whether their tweets rise to the level of journalistic significance,” she says. The Guardian’s Oliver Burkeman agrees that a journalist’s right to source from the public record is just the beginning of the conversation. “I think there’s a distinction to be made between what’s public, what’s private, and what’s ethical,” he says. “The implicit definition of ‘public’ that’s being bandied around seems to be anything that’s technically possible to access without breaking a law. But obviously, our definitions of public and private are social constructs. It’s important for us to keep negotiating where that boundary is.”

Even the most private of Twitter users aren’t just individuals, tweeting into the void. They’re also members of ad hoc communities that coalesce around shared identities—everything from sexual assault survivors to students at a specific high school—and they each have their own standards of communication that outside journalists might not understand. Hilton says she’s proud of how Testa handled the story, but the incident has inspired BuzzFeed to have more explicit internal conversations about how reporters ought to conduct themselves online.

“Twitter is public. That’s true. But we also have to think about the best way to cultivate sources in online communities, and the best way to get a community to trust you if you’re reporting on an issue that’s important to them,” Hilton says.

NPR’s rules for social media also focus on this community model, urging reporters to recognize “that different communities—online and offline—have their own culture, etiquette, and norms, and be respectful of them. Our ethics don’t change in different circumstances, but our decisions might.”

But while it’s nice for journalists to be mindful of community standards and careful with inexperienced sources, they’re ultimately accountable to their readers, and that means they can’t always prioritize a source’s expectations over the imperative to share news. “I’m hesitant to say that journalists need to ask permission to publish anything,” Holmes says. “There are some people who are naïve to how their words might [be] viewed by journalists, but there are others who just want to be able to control the attention they get.” To Holmes, “Journalists should not feel obligated to ask for permission, but they should feel obligated to be thoughtful. I think a lot of them are. Most of them are not interested in throwing Twitter followers to the wolves.” And journalists need to set standards that they’re capable of executing fairly. While many journalists are sympathetic to sources who are tweeting constructively about sexual assault, few are demanding equal rights for those who take to Twitter to spew vile racist commentary. “I’ve seen a lot of inconsistency in the application of some of these expectations,” Holmes says. “It often seems like the rules should only apply to the good guys, and that’s just not a serious way of thinking—you can’t just divvy up the world that way.”

While journalists and sources negotiate their roles on social media, it’s worth remembering that this new public landscape is ultimately sculpted by technology companies such as Twitter, which are incentivized to make all of our conversations public and swiftly embeddable in order to monetize our words and keep us coming back to share more. “We’ve built ourselves a panopticon in which any one of us can be singled out for minor transgressions and transformed into a meme for jeering global flagellation,” the Nation’s Michelle Goldberg wrote after one notable public shaming of a Twitter user’s racist joke. In an essay in the New Inquiry last week, journalist Natasha Lennard noted that the same technologies that have allowed citizens to organize for social change also “offer us up as ripe for constant surveillance.”

Twitter has the power to employ technological fixes to help clarify some of the ambiguities that its platform presents to its users. YouTube allows users to decide whether to make their videos instantly embeddable on other platforms, and Flickr prompts photographers to clarify whether and how their images can be co-opted by others. “What is the fair use standard for Twitter?” Franke-Ruta asks. “It might be interesting to have better user tools for controlling how your conversation is reproduced. There might be some third space evolved between a locked Twitter account and a public news feed.”

But it’s in Twitter’s best interest to spread its users’ messages far and wide, regardless of the ethical questions the functionality presents. “Twitter wants people to embed. They’ve made it very easy and they’ve encouraged it,” Hilton says. “But what Twitter makes possible is not always the best thing for a journalist to do.”

*Correction, March 21, 2014: This article originally misstated that Christine Fox runs a baking business out of her home; though she used to, she no longer does. It has also been updated to reflect that supporters of Fox have asked both BuzzFeed and Poynter to retract their stories. (Return.)