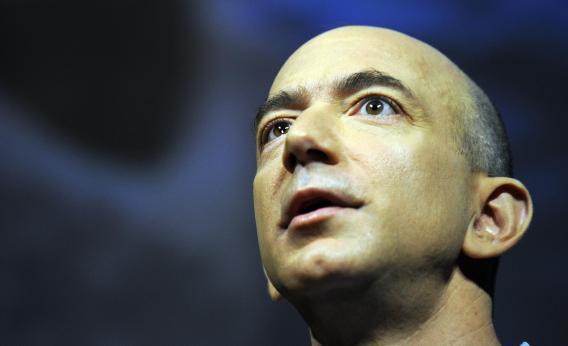

If I worked at the Washington Post—or even I just lived in Washington and yearned for the prosperity of my local paper—I’d be concerned about one line in Jeff Bezos’ otherwise pretty great note to Post employees: “I won’t be leading the Washington Post day-to-day,” the Amazon founder wrote. In my fantasy world, Bezos would reconsider. He’d find time in his packed schedule to figure out a new path for the Post. If not day-to-day then at least week-to-week, he’d work to do for the newspaper industry what he did for the shopping business: Find a way to reinvent an old game.

I’ll admit this is an outside hope. As a billionaire many times over, the most obvious and immediate benefit Bezos brings to the Post is his bottomless wallet. Last week, the Washington Post Co.—which owns Slate, which is not being sold as part of this deal—reported that in the the first six months of the year, its newspaper division saw an operating loss of $49 million. That was partly a result of increased severance expenses, but the newspaper division has been losing gobs of money for years: $54 million in 2012, $21 million in 2011, $10 million in 2010. Every year, the explanation for these losses is essentially the same: Print circulation and advertising kept going down, and online advertising and reductions in headcount weren’t making up the difference.

Bezos solves this problem by his very presence. There’s a scene in Citizen Kane in which one of Charles Foster Kane’s antagonists points out that the mogul is losing $1 million a year on his strange newspaper business. “You’re right, we did lose a million this year,” Kane shoots back. “We expect to lose a million next year, too. … At the rate of a million a year, we’ll have to close the place in sixty years.” Bezos beats Charles Foster Kane by a mile. If you assume the worst—that his Amazon holdings will never rise and that the Post continues to lose on the order of $50 to $100 million a year (neither of which is likely)—Bezos will be able to absorb the paper’s losses for at least the next 250 years.

But billionaires are a dime a dozen. Bezos’ real value to the Post—the reason that people in the media are both shocked and optimistic about this deal—isn’t what’s in his wallet. It’s what’s in his head. As a businessman, Bezos has three signature traits. He’s relentlessly focused on pleasing customers, even to the short-term detriment of his company’s bottom line. He’s uncommonly patient, willing to give good ideas years to play out before expecting a pay off. (That’s related to another trait—his ability to beguile markets into giving him carte blanche to do whatever he wants, even skate by on razor-thin profits indefinitely.) Most importantly, though, Bezos is fascinated by novel business models; he’s constantly on the hunt for new ways to sell groceries, cloud services, media, and everything else (see Amazon Prime, Web Services, etc.).

The newspaper industry happens to need every one of these skills. Most desperately, though, it needs a new business model. For years, the discussions in the industry have been dismally one-dimensional: Should we charge readers for Web access or should we be free? Not only is this a stale debate, it does not even address the primary problem that has led to the industry’s demise.

For decades, newspapers made money by bundling two distinct kinds of data: low-cost information and high-cost news. The information—classifieds, stocks, sports scores, weather, entertainment listings, recipes, horoscopes, coupons, police blotters, obits—was widely popular and cheap and easy to produce. The news was less popular, more expensive to produce, and often risky. For certain kinds of investigative stories, newspapers could bankroll salaried employees who spent months pursuing trails that went nowhere. Sometimes following a burglary leads to a cover-up that leads to impeachment; most times, it doesn’t. But newspapers don’t know which is which unless they spend money digging. Despite the uncertainty, newspapers worked as a business, because they had a monopoly on the low-cost information. As long as there was no other place for their audience to go to for classifieds and all the rest, readers and advertisers kept paying for the ink, indirectly subsidizing the serious stuff.

Then the Internet came along and killed that monopoly. It set low-cost information free, and by lowering the cost of publication, it allowed bloggers to replicate a portion of the newspapers’ newsgathering efforts. But not all of it: No one has yet been able to find a way to profitably produce the kind of risky, expensive investigative and foreign reporting that newspapers like the Post now invest in. Yes, there are websites—Slate included—that do some version of this. But in general, if newspapers go away, we’ll have less deep reporting than we used to. That’s the problem Bezos can potentially solve.

Bezos is a maven of finding new ways to sell old things. When the first Kindle came out, he brilliantly bundled cellular coverage into the price, letting you forget about the data charge while you downloaded lots of books. Later, he released a low-priced Kindle that was subsidized by ads on the lock screen; when that version turned out to be popular, ads became the default on every e-ink Kindle.

Or look at Amazon Prime, which is nothing but a way to bulk-sell shipping charges. By hooking you with a $79 free-shipping subscription, Bezos wins either way. He gets your money even if you never shop at Amazon again. More likely, your “free” shipping deal subtly alters your psychology—thanks only to this business model, you’ll remember Amazon every time you think of something you want to buy. I was recently looking back at my Amazon order history. Before 2006, the year I first signed up for Prime, I placed less than 10 orders per year at the site. Prime completely changed my shopping habits. In my first year with the service, I placed 46 orders. This year my household is on track to quadruple that.

Bezos is also a master of finding ways to sell every one of his innovations multiple times. What did he do after building a world-class warehouse and shipping network? He leased it out to other retailers, letting anyone list their wares on Amazon’s site and even ship from its warehouses. Amazon only gets a commission on these third-party sales, but since the warehouses and shipping infrastructure were already built, that commission is quite profitable. And it’s growing rapidly, with third-party sales now surging faster than the rest of Amazon’s sales.

Bezos did a similar thing with his servers. To run its own business, Amazon had to create an accessible server infrastructure that could be used by developers across the company. As Bezos told Wired in 2011, after building it, “we realized, ‘Whoa, everybody who wants to build web-scale applications is going to need this.’ We figured with a little bit of extra work we could make it available to everybody. We’re going to make it anyway—let’s sell it.”

None of this directly applies to the newspaper business, but these ideas give you a sense of what true business-model innovation looks like. It’s not just figuring out how to build a paywall. For the newspaper industry, finding a new way to make money will involve taking a deeper look at all its assets: its staff’s talents, the data its readers generate, the trucks that deliver its newsprint, its access to sources—and figuring out how to monetize them in ways that haven’t been tried before. The news business presents special restrictions on some of these experiments; Bezos would have to steer away from any business model that calls into question the Post’s integrity. But that’s obvious, and there’s room to innovate within the bounds of journalistic ethics.

At least, I hope there is, and that Bezos spends some time searching for those innovations. I know he’s got a demanding day job. But newspapers are just as important as same-day shipping. He’s given the Post a new lease on life. But what would really help is a couple of billion-dollar ideas.