The National Security Agency has been collecting the phone records of all U.S. citizens—which numbers have called which other numbers, when, and for how long—in an enormous database. The government says this mass collection is OK because the database is “queried”—i.e., searched—only under court supervision. In theory, this two-tiered approach, with judicial scrutiny applied at the query stage rather than the collection stage, is defensible. But does the judiciary—in this case, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court—really examine the database queries?

This week, at House and Senate hearings, five administration officials answered questions about the phone surveillance program. They held back plenty, but they told us a lot more than we had previously known. They testified that last year, the NSA had plugged fewer than 300 phone numbers into the database— numbers for which the agency could claim a “reasonable, articulable suspicion” of a connection to terrorism—to find out which other phones had called or received calls from those numbers. The officials cited multiple layers of supervision. But the judicial review they described is superficial. The NSA doesn’t have to get court approval each time it queries the database. It doesn’t even have to explain each query to the court afterward.

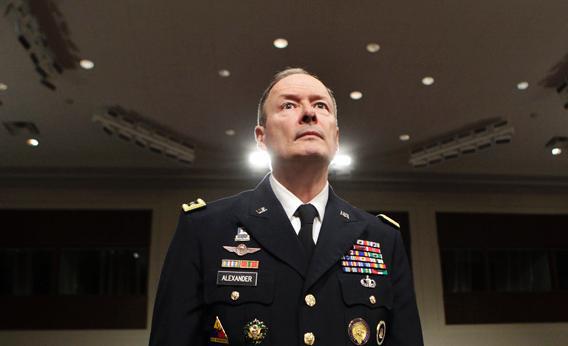

The officials who testified were NSA Director Keith Alexander, Deputy NSA Director Chris Inglis, Deputy Attorney General James Cole, FBI Director Robert Mueller, and Robert Litt, the general counsel to the director of national intelligence. Here are the key questions they addressed:

1. Who has access to the data?

“Only 20 analysts and NSA and their two managers, for a total of 22 people, are authorized to approve numbers that may be used to query this database,” Inglis testified. Mueller quoted the same figure: “You have just 22 persons who have access to this to run the numbers against the database—20 analysts and two supervisors.” Alexander elaborated:

“Could somebody get out and get your phone number and see that you were at a bar last night? The answer is no, because, first, in our system, somebody would have had to approve, and there’s only 22 people that can approve a reasonable, articulable suspicion on a phone number. So, first, that [phone number] has to get input. Only those phone numbers that are approved could then be queried. And so you have to have one of those 22 [people] break a law.”

These statements don’t clarify whether the “access” reserved to these 22 people is a physical or just a legal matter. Is it possible for others to access the data? That raises the next question:

2. What are the barriers to unauthorized access?

Alexander testified, “To get to any data like the business records 215 data that we’re talking about, that’s in an exceptionally controlled area. You would have to have specific certificates to get into that.” Inglis told lawmakers that “the metadata is segregated from other data sets held by NSA.” Cole added that it’s “stored in repositories at NSA that can only be accessed by a limited number of people.” These statements imply that real barriers in physical or cyberspace protect the data. But what are the barriers? How is access controlled?

3. Can one person search the data alone?

Not legally. “Any analyst that wants to form a query, regardless of whether it’s this authority or any other, essentially has a two-person control rule,” said Inglis. “They would determine whether this query should be applied, and there is someone who provides oversight on that.” Again, it isn’t clear whether this rule is just a legal requirement or is physically enforced by a dual-key system.

4. Does the NSA have to get prior court approval for each query?

No. Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., asked, “Every time you make the query, does that have to be approved by the court?” Cole answered, “We do not have to get separate court approval for each query. … We don’t go back to the court each time.” Cole noted that the judges, up front, “set out the standards for us to use,” including the “reasonable suspicion” standard. But “we don’t give the reasonable suspicion to the court ahead of time.”

Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Mich., the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, didn’t like the oversight gap Schiff had exposed. Rogers has repeatedly assured Americans that the data are kept in a “lockbox.” To shore up this story, Rogers stepped in with a friendly question for Cole: “My understanding, though, is that every access is already pre-approved; that the way you get into the system is court-approved. Is that correct?” Cole replied: “That’s correct. The court sets out the standards which have to be applied to allow us to make the query in the first place.”

In other words, the court categorically pre-approves all queries that meet the “reasonable, articulable suspicion” standard. The NSA then applies that standard as it sees fit. No presentation of evidence to the court is required.

5. What restrictions does the court prescribe for all searches?

We don’t know. The “reasonable, articulable suspicion” standard, on its face, is vague. Cole testified that a secret, unpublished court order “goes into, in great detail, what we can do with that metadata, how we can access it, how we can look through it, what we can do with it once we have looked through it.” He said the order includes “restrictions on who can access it” as well as “minimization procedures” to protect innocent people from investigation. The order might resemble documents, published yesterday by the Guardian, that outline such rules for the NSA’s Internet surveillance program. But when lawmakers asked whether the administration would release the court order governing phone metadata, Litt said only that his office was working on it. Until then, descriptions of what’s in the order are just assertions.

6. Does the NSA submit each query for court review afterward?

No. Schiff asked: “Does the court scrutinize, after you present back to the court, ‘These are the occasions where we found reasonable and articulable facts’? Do they scrutinize your basis for conducting those queries?” Cole replied, “Yes, they do.” But a few minutes later, Cole corrected himself: “The FISC does not review each and every ‘reasonable, articulable suspicion’ determination. What does happen is they are given reports every 30 days in the aggregate. And if there are any compliance issues, if we found that it wasn’t applied properly, that’s reported separately to the court.”

Schiff pressed for clarification: “I just want to make sure I understood what you just said. A prior court approval is not necessary for a specific query, but when you report back to the court about how the order has been implemented, you do set out those cases where you found reasonable, articulable facts and made a query. Do you set out those with specificity, or you just say, ‘On 15 occasions we made a query’?’” Cole answered: “It’s more the latter, the aggregate number where we’ve made a query. And if there’s any problems that have been discovered, then we, with specificity, report to the court those problems.”

Cole and other officials said the queries are tightly documented and reviewed by the Department of Justice. But the bottom line is that the executive branch reports to the court only those cases which the administration itself has flagged as possible abuses.

7. Does the court provide any meaningful resistance?

Litt testified that it does:

“People point to the fact that the FISA court ultimately approves almost every application that the government submits to it. But this does not recognize the actual process … When we prepare an application for a FISA … we first submit to the court what’s called a read copy, which the court’s staff will review and comment on. And they will almost invariably come back with questions, concerns, problems that they see, and there’s an iterative process back and forth between the government and the FISA court to take care of those concerns, so that at the end of the day we’re confident that we’re presenting something that the FISA court will approve. That is hardly a rubber stamp.”

That sounds great. But where’s the evidence of all this back and forth? What Litt is describing wouldn’t even be discernible in the court orders.

The Obama administration deserves credit for adding layers of oversight to the phone records program (which began under President Bush) and for answering questions about it in open hearings. We know more now than we did before. But part of what we’ve learned is that the judicial oversight is lax. The NSA doesn’t have to get court approval for each query. Its searches are collectively “pre-approved,” based on vague standards that the agency itself gets to interpret. Nor does it have to justify each query afterward. It reports to the court only those queries which the administration acknowledges were problematic. Officials tell us there are detailed demands and rules, issued by the court, that limit how the NSA can use the data. But they haven’t shown us any documentation of those demands or rules.

In short, the NSA, having collected everyone’s phone records, can and does search them without specific warrants. Its case-by-case decisions aren’t closely scrutinized by any other branch of government. That’s unacceptable.

William Saletan’s latest short takes on the news, via Twitter: