I’m going to keep this brief, because you’re not going to stick around for long. I’ve already lost a bunch of you. For every 161 people who landed on this page, about 61 of you—38 percent—are already gone. You “bounced” in Web traffic jargon, meaning you spent no time “engaging” with this page at all.

So now there are 100 of you left. Nice round number. But not for long! We’re at the point in the page where you have to scroll to see more. Of the 100 of you who didn’t bounce, five are never going to scroll. Bye!

OK, fine, good riddance. So we’re 95 now. A friendly, intimate crowd, just the people who want to be here. Thanks for reading, folks! I was beginning to worry about your attention span, even your intellig … wait a second, where are you guys going? You’re tweeting a link to this article already? You haven’t even read it yet! What if I go on to advocate something truly awful, like a constitutional amendment requiring that we all type two spaces after a period?

Wait, hold on, now you guys are leaving too? You’re going off to comment? Come on! There’s nothing to say yet. I haven’t even gotten to the nut graph.

I better get on with it. So here’s the story: Only a small number of you are reading all the way through articles on the Web. I’ve long suspected this, because so many smart-alecks jump in to the comments to make points that get mentioned later in the piece. But now I’ve got proof. I asked Josh Schwartz, a data scientist at the traffic analysis firm Chartbeat, to look at how people scroll through Slate articles. Schwartz also did a similar analysis for other sites that use Chartbeat and have allowed the firm to include their traffic in its aggregate analyses.

Schwartz’s data shows that readers can’t stay focused. The more I type, the more of you tune out. And it’s not just me. It’s not just Slate. It’s everywhere online. When people land on a story, they very rarely make it all the way down the page. A lot of people don’t even make it halfway. Even more dispiriting is the relationship between scrolling and sharing. Schwartz’s data suggest that lots of people are tweeting out links to articles they haven’t fully read. If you see someone recommending a story online, you shouldn’t assume that he has read the thing he’s sharing.

OK, we’re a few hundred words into the story now. According to the data, for every 100 readers who didn’t bounce up at the top, there are about 50 who’ve stuck around. Only one-half!

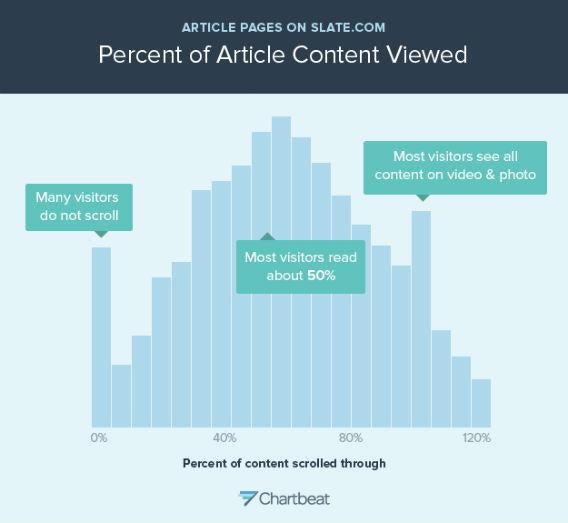

Take a look at the following graph created by Schwartz, a histogram showing where people stopped scrolling in Slate articles. Chartbeat can track this information because it analyzes reader behavior in real time—every time a Web browser is on a Slate page, Chartbeat’s software records what that browser is doing on a second-by-second basis, including which portion of the page the browser is currently viewing.

A typical Web article is about 2000 pixels long. In the graph below, each bar represents the share of readers who got to a particular depth in the story. There’s a spike at 0 percent—i.e., the very top pixel on the page—because 5 percent of readers never scrolled deeper than that spot. (A few notes: This graph only includes people who spent any time engaging with the page at all—users who “bounced” from the page immediately after landing on it are not represented. The X axis goes beyond 100 percent to include stuff, like the comments section, that falls below the 2,000-pixel mark. Finally, the spike near the end is an anomaly caused by pages containing photos and videos—on those pages, people scroll through the whole page.)

Courtesy of Chartbeat

Chartbeat’s data shows that most readers scroll to about the 50 percent mark, or the 1,000th pixel, in Slate stories. That’s not very far at all. I looked at a number of recent pieces to see how much you’d get out of a story if you only made it to the 1,000th pixel. Take Mario Vittone’s piece, published this week, on the warning signs that someone might be drowning. If the top of your browser reached only the 1,000th pixel in that article, the bottom of your browser would be at around pixel number 1,700 (the typical browser window is 700 pixels tall). At that point, you’d only have gotten to warning signs No. 1 and 2—you’d have missed the fact that people who are drowning don’t wave for help, that they cannot voluntarily control their arm movements, and one other warning sign I didn’t get to because I haven’t finished reading that story yet.

Or look at John Dickerson’s fantastic article about the IRS scandal or something. If you only scrolled halfway through that amazing piece, you would have read just the first four paragraphs. Now, trust me when I say that beyond those four paragraphs, John made some really good points about whatever it is his article is about, some strong points that—without spoiling it for you—you really have to read to believe. But of course you didn’t read it because you got that IM and then you had to look at a video and then the phone rang …

The worst thing about Schwartz’s graph is the big spike at zero. About 5 percent of people who land on Slate pages and are engaged with the page in some way—that is, the page is in a foreground tab on their browser and they’re doing something on it, like perhaps moving the mouse pointer—never scroll at all. Now, do you know what you get on a typical Slate page if you never scroll? Bupkis. Depending on the size of the picture at the top of the page and the height of your browser window, you’ll get, at most, the first sentence or two. There’s a good chance you’ll see none of the article at all. And yet people are leaving without even starting. What’s wrong with them? Why’d they even click on the page?

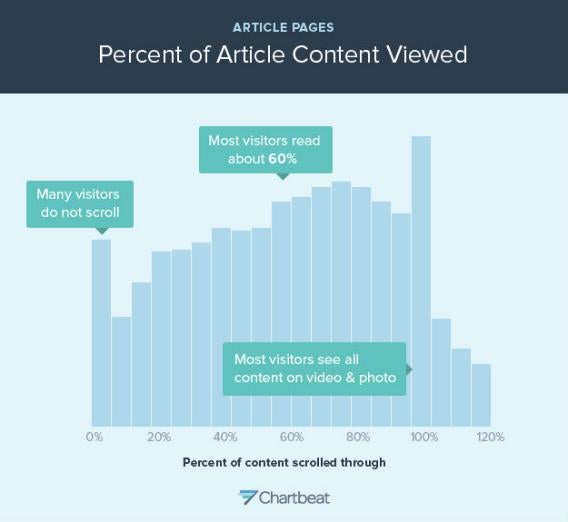

Schwarz’s histogram for articles across lots of sites is in some ways more encouraging than the Slate data, but in other ways even sadder:

Courtesy of Chartbeat

On these sites, the median scroll depth is slightly greater—most people get to 60 percent of the article rather than the 50 percent they reach on Slate pages. On the other hand, on these pages a higher share of people—10 percent—never scroll. In general, though, the story across the Web is similar to the story at Slate: Few people are making it to the end, and a surprisingly large number aren’t giving articles any chance at all.

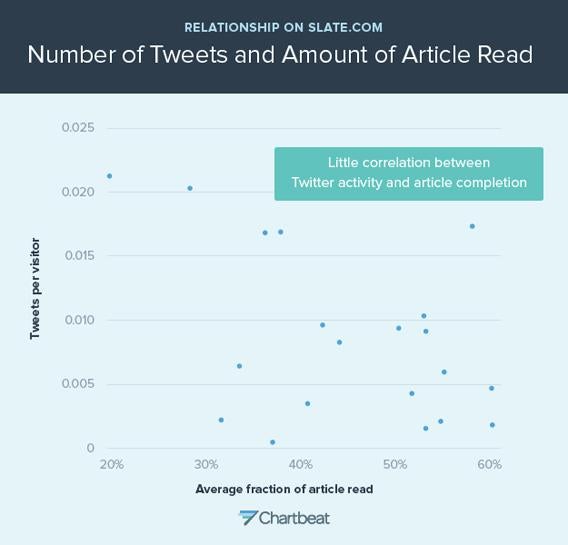

We’re getting deep on the page here, so basically only my mom is still reading this. (Thanks, Mom!) But let’s talk about how scroll depth relates to sharing. I asked Schwartz if he could tell me whether people who are sharing links to articles on social networks are likely to have read the pieces they’re sharing.

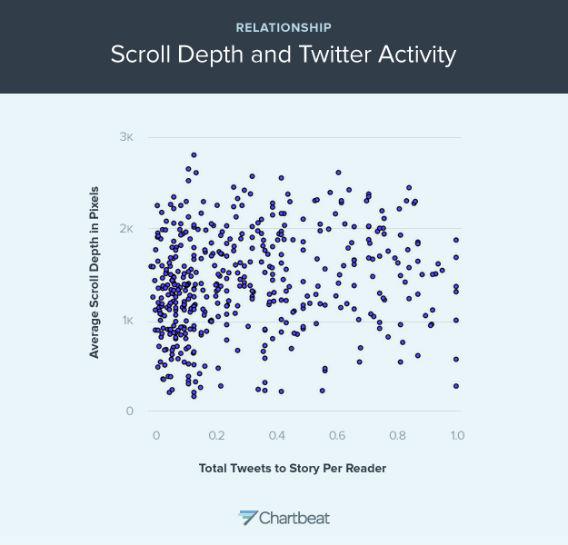

He told me that Chartbeat can’t directly track when individual readers tweet out links, so it can’t definitively say that people are sharing stories before they’ve read the whole thing. But Chartbeat can look at the overall tweets to an article, and then compare that number to how many people scrolled through the article. Here’s Schwartz’s analysis of the relationship between scrolling and sharing on Slate pages:

Courtesy of Chartbeat

Courtesy of Chartbeat

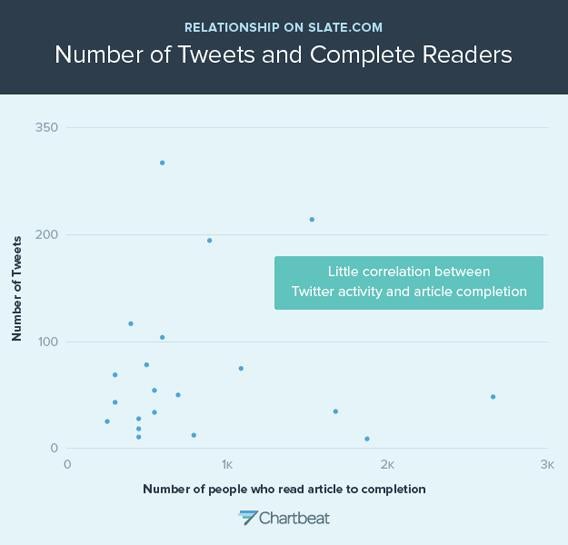

And here’s a similar look at the relationship between scrolling and sharing across sites monitored by Chartbeat:

Courtesy of Chartbeat

They each show the same thing: There’s a very weak relationship between scroll depth and sharing. Both at Slate and across the Web, articles that get a lot of tweets don’t necessarily get read very deeply. Articles that get read deeply aren’t necessarily generating a lot of tweets.

As a writer, all this data annoys me. It may not be obvious—especially to you guys who’ve already left to watch Arrested Development—but I spend a lot of time and energy writing these stories. I’m even careful about the stuff at the very end; like right now, I’m wondering about what I should say next, and whether I should include these two other interesting graphs I got from Schwartz, or perhaps I should skip them because they would cause folks to tune out, and maybe it’s time to wrap things up anyway …

But what’s the point of all that? Schwartz tells me that on a typical Slate page, only 25 percent of readers make it past the 1,600th pixel of the page, and we’re way beyond that now. Sure, like every other writer on the Web, I want my articles to be widely read, which means I want you to Like and Tweet and email this piece to everyone you know. But if you had any inkling of doing that, you’d have done it already. You’d probably have done it just after reading the headline and seeing the picture at the top. Nothing I say at this point matters at all.

So, what the hey, here are a couple more graphs, after which I promise I’ll wrap things up for the handful of folks who are still left around here. (What losers you are! Don’t you have anything else to do?)

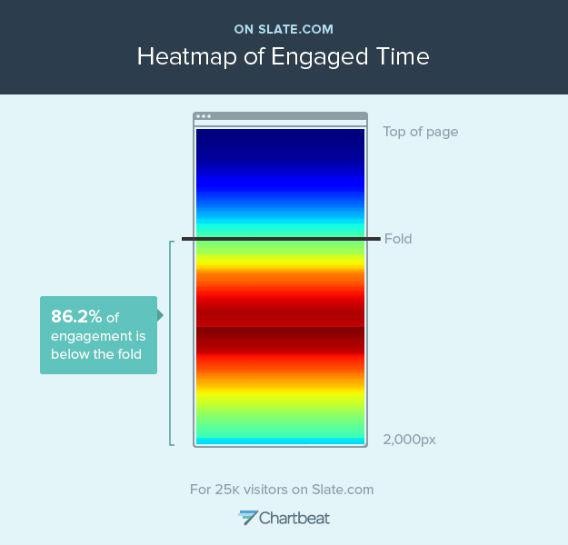

This heatmap shows where readers spend most of their time on Slate pages:

Courtesy of Chartbeat

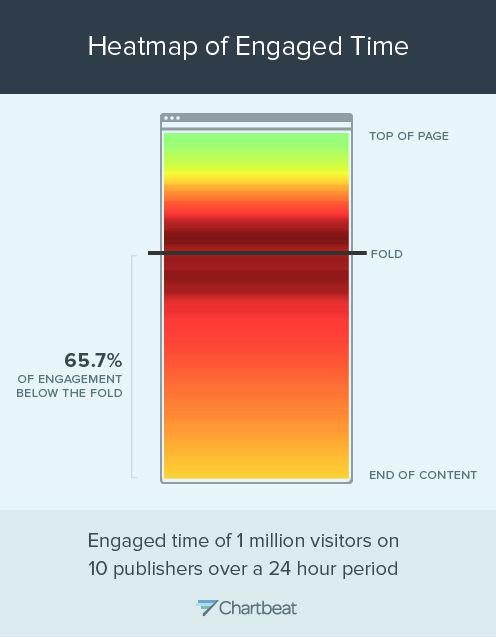

And this one shows where people spend time across Chartbeat sites:

Courtesy of Chartbeat

Schwartz told me I should be very pleased with Slate’s map, which shows that a lot of people are moved to spend a significant amount of their time below the initial scroll window of an article page. On Chartbeat’s aggregate data, about two-thirds of the time people spend on a page is “below the fold”; on Slate, that number is 86.2 percent. “That’s notably good,” Schwartz told me. “We generally see that higher-quality content causes people to scroll further, and that’s one of the highest below-the-fold engagement numbers I’ve ever seen.”

Yay! Well, there’s one big caveat: It’s probably Slate’s page design that’s boosting our number there. Since you usually have to scroll below the fold to see just about any part of an article, Slate’s below-the-fold engagement looks really great. But if articles started higher up on the page, it might not look as good.

In other words: Ugh.

Finally, while I hate to see these numbers when I consider them as a writer, as a reader I’m not surprised. I read tons of articles every day. I share dozens of links on Twitter and Facebook. But how many do I read in full? How many do I share after reading the full thing? Honestly—and I feel comfortable saying this because even mom’s stopped reading at this point—not too many. I wonder, too, if this applies to more than just the Web. With ebooks and streaming movies and TV shows, it’s easier than ever, now, to switch to something else. In the past year my wife and I have watched at least a half-dozen movies to about the 60 percent mark. There are several books on my Kindle I’ve never experienced past Chapter 2. Though I loved it and recommend it to everyone, I never did finish the British version of the teen drama Skins. Battlestar Galactica, too—bailed on it in the middle, hoping to one day jump back in. Will I? Probably not.

Maybe this is just our cultural lot: We live in the age of skimming. I want to finish the whole thing, I really do. I wish you would, too. Really—stop quitting! But who am I kidding. I’m busy. You’re busy. There’s always something else to read, watch, play, or eat.

OK, this is where I’d come up with some clever ending. But who cares? You certainly don’t. Let’s just go with this: Kicker TK.