You wouldn’t know it to look at the products, but the school yearbook business is kind of shady. There’s a good chance you and your kid’s school are paying way too much for yearbooks—sometimes thousands or tens of thousands a year too much.

Here’s how the traditional yearbook business works: When big yearbook providers sign up with a school, they ask the school to predict how many books it will need for the year. These estimates are due months before graduation. Because class sizes and demographics shift from year to year—and because some kids have stopped buying yearbooks altogether, thanks perhaps to Facebook—yearbook advisers don’t have much to go on when they’re making their guesses.

For schools and for parents, there are big costs to guessing wrong. If a school orders too few yearbooks, some kids who want a book will go without. That’s why schools tend to err on the side of guessing high—and then get stuck with unsold yearbooks, and a huge bill to the yearbook company. To cover costs of overprinting, some schools add an extra fee to the yearbooks—$10 or $20 per copy that you, the parent, must pay. Even so, lots of schools end up in hock to their yearbook providers. For instance, over the last few years, George Washington High School in San Francisco, one of the largest schools in the city, has had to eat the cost of so many unsold books that it now owes its yearbook company $50,000, according to the school’s yearbook adviser.

When Aaron Greco, a young tech entrepreneur, started sniffing around the yearbook business a few years ago, he was surprised by these shenanigans. The fundamental problem with the yearbook business, he realized, was that big yearbook providers were producing their books using offset printing—an expensive printing system that’s great for books with large print runs but that leads to high costs and little flexibility for yearbooks, whose print runs number in the hundreds or low thousands. Over the past decade, we’ve seen the rise of digital on-demand printing, which is now commonly used for photo books (the sort you order from Shutterfly or Blurb) and self-publishing. Greco had a brilliant idea: Why not use the same printing process for yearbooks?

Thus was born TreeRing, Greco’s four-year-old yearbook startup, which now serves 2,000 schools across the country and will produce about 200,000 yearbooks this year. By printing yearbooks on demand, TreeRing beats traditional yearbook companies in pretty much every way.

When schools sign up with TreeRing, they don’t have to pay anything to the company—TreeRing’s only economic relationship is with parents who buy the yearbooks, so schools will never end up in debt to the firm. What’s more, the school doesn’t have to make a guess about how many yearbooks it needs, because TreeRing prints a book only after a student orders it. Digital printing also lets students customize their books—in addition to the “core” yearbook produced by the yearbook class, kids can add more pages that they design themselves. Finally—because schools don’t have to bake in the cost of overprinting, and because TreeRing prints books in the spring, when there’s excess capacity at on-demand printing facilities—TreeRing’s yearbooks are often cheaper than those offered by traditional yearbook providers.* TreeRing sells a 140-page hardcover yearbook—the average size for a high school—for around $50. That’s about $25 less than the price of a traditional high school yearbook.

“When we go out to talk to schools and tell them what we do, there’s only one question we get,” Greco told me when I met him at TreeRing’s offices earlier this month: “ ‘What’s the catch?’ ” I wondered the same thing. At first, I suspected that TreeRing’s yearbooks might not look as good as those produced by offset printing. But Greco showed me a sample yearbook that looked great—the paper and print quality was fantastic, and the hardcover was glossy and substantial. It looked just as good as any school yearbook I’ve ever seen.

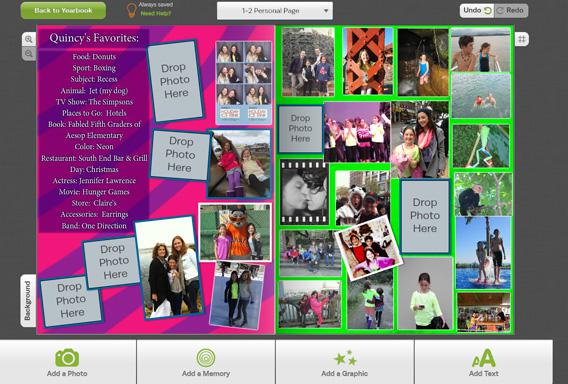

Then I wondered if working on TreeRing’s yearbooks might be more difficult for schools’ yearbook staff and students. But Greco showed me the firm’s Web-based software, which works on even the most ancient machines, and which is drop-dead easy to learn. What’s more, because TreeRing saves all its pages in the cloud, schools don’t have to worry about backing up their stuff, and they can’t lose months of work when computers crash. TreeRing’s model also lets parents and students share photos with the yearbook class online. For instance, if the yearbook staff didn’t send a photographer to the baseball game but a parent happened to get a great shot of a senior sliding into home plate, the staff can use that photo in the book.

And there’s one more thing: Because TreeRing’s books are printed on demand, the company doesn’t impose stiff printing deadlines on the school’s yearbook staff. Big yearbook companies often want a fully completed yearbook several months before graduation—so events from the spring, like prom, can’t be in the book. TreeRing takes just four weeks to print and deliver books, so the yearbook actually includes most of the school year. (Like traditional yearbooks, TreeRing delivers its books just before school ends, but kids can always order copies later.)

Some traditional yearbook firms have begun to add features that compete with TreeRing’s books. For instance, Jostens, the granddaddy of the yearbook biz, now lets schools add customizable pages to their books. But Jostens only allows up to four custom pages, and it charges $15 extra for the option. TreeRing’s books come with two free custom pages, and parents can buy more for $2 per page, and there’s no limit to how many they can add. What’s more, Jostens still uses a network of sales reps to sell to schools—which is more expensive than TreeRing’s online model. And it still requires schools to sign a contract that includes an estimated print run, which leads to expensive overruns.

Greco managed to convince me that TreeRing’s model was better than that of traditional companies. But I did wonder one more thing—was his business doomed in the long run? As more and more of our kids’ lives move online, they no longer need printed books to remember what happened in school. You can always just flip back on your Facebook timeline—and Facebook has the added benefits of including just your friends and making you the center of attention. So why buy a yearbook?

Predictably, Greco believes there’s a big future in printed books, despite Facebook’s intrusion into our lives. He points out that even though we all take pictures on digital cameras, photo-printing companies like Shutterfly are experiencing huge growth. “People still want printed things, but they need to be curated—they need to be valuable,” says Greco. In addition to letting kids add their own custom pages to their yearbooks, TreeRing also adds social-networking features—for instance, kids can offer testimonials and even “sign” each other’s pages before the book is printed. (Your pre-printed “signature” is your photo and your name in a handwriting font, though you could also include a picture of an actual handwritten note.)

In this way, Greco sees TreeRing’s books as the perfect yearbook for the digital age. If you’re the kind of kid who wouldn’t normally make much of an appearance in the yearbook—you’re shy, you’re unpopular, you feel you’re above everyone else at your godforsaken school—at least you’ll be able to have a yearbook that doesn’t sideline you. So maybe you’ll want the yearbook that stars you, even if, in most other things, paper is dead to you.

Correction, May 28, 2013: This article originally and incorrectly said that TreeRing does its printing in the summer.