It’s a great time to be a professional creator—or to become one. Want to be a digital artist? Put your stuff up on DeviantArt. The crafty can open an Etsy shop, and aspiring musicians can share their tunes on YouTube. (Just don’t be try to be the next Nicki Minaj, for the love of all that is good—one is enough.)

Me, I have always wanted to be a voice actor—especially for video games. But because “Hey Dad, I’m going to do silly voices for a living!” wouldn’t have gone so well, I tucked that dream away for many years. I still did silly voices all the time, in the process driving off several girlfriends, but getting paid to do it never seemed possible.

Early last year, however, I was faced with a debilitating illness that forced me to reassess my relationship with my voice. I was diagnosed with what doctors call nasopharyngitis, known to laypeople as a “cold.” OK, I’m being a little dramatic, but the resulting ear infection left me partially deafened, and surgery exacerbated the problem. Facing the prospect of significant hearing loss, I realized I really need to do this. I need to give this voice-acting thing a shot.

My little epiphany couldn’t have been at a better time. In recent years, the Internet has eroded the barriers to content creation to the point where talent and drive are often the biggest factors in success, not marketing budgets or licensing deals. Sure, I still started out in the old-fashioned way: looking for an agent. Much to my delight, I even found one. But the gigs didn’t come in. I waited. I called. I heard nothing whatsoever. After six months, it was clear that I had to take the dream-realizing into my own hands. Right now, the greatest show in town for dream-making and dream-breaking is Kickstarter, home of the iPhone coffee cup holder and the point-and-click adventure game resurgence. Anyone can post a project on Kickstarter and watch funders come in—or watch his hopes die. Certain fields best tend to do particularly well on Kickstarter: music, film, art—and video games. Thanks to crowdfunding, upstart independent gaming companies that are beginning to make their mark, right at the same time I’m trying to make my voice heard. There, I caught a whiff of opportunity: Even when Kickstarter projects are successful, they often operate on a very tight budget—too tight to afford big, established actors to voice their games. I smelled opportunity.

I started sending my demos to successful Kickstarter projects that I was interested in, particularly the smaller studios with a lot of heart. And lo, I got some responses! My first bite came from the Quest for Infamy project, a dark-comedy take on the old Quest for Glory games of the early ’90s. The Quest for Glory series fused the point-and-click adventure genre with role-playing games; so story and dialogue were paramount, but they were tied in seamlessly with your character’s stats. The game had you playing as a recent graduate of hero school who takes on a town’s longstanding ills for the greater good, putting your degree to immediate use. Obviously, it was a tale for a different age. Quest for Infamy has much the same setup, only you play as a ne’er-do-well who only wishes to be as infamous as possible, thus the title.

I was already interested in Quest for Infamy in a nonprofessional capacity, because in middle school I was a tremendous nerd who talked about Quest for Glory endlessly at the lunch table. Over what I called “Sponge Pizza” (you know of what I write, school lunch survivors), we’d strategize about how we approached obstacles in the game: one person might break into a shop by kicking down the door after significant strength training, another might use a magic spell. The charm lay in finding your own solution to whatever problem you came across. Kind of like Scribblenauts, but with more story and fewer octopodes in top hats.

Game designer Steven Alexander (known as “Blackthorne” in developer land) started planning Quest for Infamy back in 2003. It was an extremely ambitious project, more than he and his team could handle at that point. To hone their skills, they remade King’s Quest III and Space Quest II—old adventure games from now-defunct Sierra On-Line, which they released freely in 2006 and 2011, respectively. Alexander had a lot of time to work on these: In 2002, he was diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. Following a rejected kidney transplant in 2003, he was bound to dialysis for many years. He was fully prepared not to survive his condition, leaving his wife the instructions and resources necessary to complete Space Quest II.

But in 2011, Alexander got a lucky break: A kidney became available for transplant. With his “extra life,” he also got the opportunity to make his dream come true. He started planning for the commercial production and release of Quest for Infamy, prepared a demo, and launched his project on Kickstarter, where it earned 253 percent of its $25,000 goal. It’s a good story—the return from the jaws of death to glory. Not so different from my cold, really.

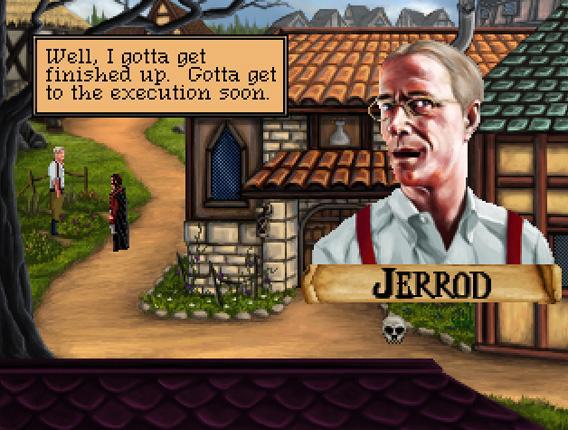

Still from Quest of Infamy, copyright 2013 by Infamous Quests

After all this, I submitted a demo and was cast as Jerrod, an overly enthusiastic apothecary in Quest for Infamy. I wanted to make sure I gave the Infamous Quests team something special, so in addition to recording several “straight” interpretations of the character, I did a joke take as an excitable German—just for funsies. I was pretty surprised when my joke character ended up as the voice for Jerrod, but this is how character acting can be: Sometimes, the character has to create itself.

As little as 20 years ago, the only indicator of a video game character was the digital image and some text. Technology limited how convincing characters could look, and text, well—let’s just say that game studios did not often employ professional writers. I won’t cite specific examples, as I will no doubt deliver countless terrible lines myself one day, but “Oh, great hero, who hath saved the realm and to whom we owe all: Wilt thou go gather me some carrots/guitars/chicken nuggets?” is still a common video game trope. But we also have characters who look real enough to fool the casual observer, accomplished writers who bring them to life, and voices to make them engaging and relatable and relay emotions in a cinematic way.

Since then, I have continued to work the independent games circuit. I’ve played a Scottish freedom fighter, a bank robber, several wizards and princes, a ’roid-raging football player, a singing support technician, ghosts, goblins, and others—including some projects that haven’t yet been announced and are still in active development.

Thanks to services like Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and Steam Greenlight, we’re in the midst of an indie video game renaissance. Crowdfunding has allowed for innovations that would be impossible otherwise: Gamasutra notes that even major studios such as Uber Entertainment and Double Fine’s game ideas “would have trouble appealing to a major publisher due to their target demographic.” Big studios using crowdfunding, however, will often rely on nostalgia or proven past works—it is most often with independent developers that true innovation happens.

And where would I be without access to these independent developers? The voice-over industry is notoriously competitive, with a few actors such as Nolan North, Jennifer Hale, or Yuri Lowenthal taking most of the available roles (jerks). With independent studios, only what you bring to the table matters. Connections, agencies, budgets—the things that make approaching a larger studio so difficult—don’t matter so much. They’re just a bunch of people who want to make something, with the Internet acting as the only mediator. And now I have a role to play here, too.

A new demo for Quest for Infamy is available now. This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.