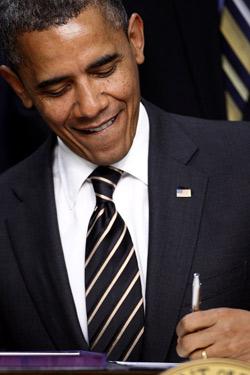

Stymied in his attempts to pass an actual jobs bill, President Obama settled on Thursday for passing something that sounds like a jobs bill. Don’t let the backronym fool you: The JOBS Act—that’s “Jumpstarting Our Business Startups”—won’t put a lot of unemployed Americans back to work right away. It doesn’t even take effect until 2013. Still, Obama was right when he called it “a potential game changer” for startups and small businesses. In the long run, it could do something that a less-targeted stimulus measure wouldn’t: level the playing field for non-Silicon Valley startups.

What’s new in the JOBS Act is a provision that legalizes “crowdfunding”—that is, for a startup to raise small amounts of cash from large numbers of ordinary people. Until now, only “accredited investors”—a euphemism for a small number of very rich people with offices on Sand Hill Road—were allowed to invest privately in most startups and small companies. As Annie Lowrey explained in Slate last fall, that places limits on the type and the number of businesses that can raise the money they need to grow. And it feels downright un-American.

Behind the seemingly unfair rules lies a reasonable intention: to protect unsophisticated investors from getting fleeced. Public companies must submit to strict disclosure rules about their corporate structure and finances; private companies could be run by pretty much anyone, from a lone genius with a dream to a ring of thieves with a plan to take your money and run. Accordingly, some commentators have slammed the JOBS Act on the grounds that the main winners will be hucksters and scammers. One blogger dubbed it the “Jump-Start Obama’s Bucket Shops” Act.

No doubt crowdfunding will attract some fraudsters. But in a refreshing instance of congressional wisdom, the bill benefited from some last-minute amendments that strengthened the disclosure requirements without adding undue red tape. And the more money you raise, the more you have to disclose, meaning that most petty crooks will reap only petty gains. There’s also talk in the nascent crowdfunding industry of forming a self-policing regulatory body.

A more serious concern is that crowdfunding will lead rookie investors to pour their savings into ventures that are well-intentioned yet doomed to fail—subprime IPOs, in the words of one wary expert. There are some checks on this in the JOBS Act, limiting both the amount a company can raise and the amount an individual can invest in a single company. Still, bad investments are inevitable. It’s well-known in Silicon Valley that only a small proportion of startups succeed. Venture capital firms are built to cushion this risk by betting on dozens or hundreds of different companies. The few that hit the jackpot cover the losses on the rest. Inexperienced investors may not diversify their portfolios to the same extent. Some will lose everything they put in.

Yet the fact that some fools will be parted from their money isn’t a good reason to object to the legalization of crowdfunding. If it were, gambling and the lottery would be first on the chopping block. And unlike in roulette, there will be winners besides the house. The question is, who will they be?

The bill’s most enthusiastic backers want you to believe that the winners will be the tech titans of tomorrow: the as-yet-undiscovered Twitters and Facebooks that have world-beating ideas and lack the visionary, risk-taking investors to make them real. That’s possible, but unlikely. The venture capital industry already has tens of thousands of professionals pouring tens of billions of dollars into any startup with a whisper of a chance of hitting it big. There are times when VCs are too loose with their money (think dot-com bubble) and times when they’re too tight (think financial crisis). And they’re often rightly criticized for bandwagon-jumping. Still, their deep pockets and tolerance for risk make them an ideal funding mechanism for ambitious startups with a long-shot chance at explosive growth.

The most promising startups have better options still, including wealthy angel investors who might be less likely than VCs to sacrifice long-term sustainability for short-term profits. And on the other side of the spectrum, well-established, traditional small businesses can still get old-fashioned bank loans. Consolidation in the banking industry has made small-business loans harder to obtain, but if you can show a track record of profits, you can still find the money you need for an expansion or capital upgrade.

The biggest winners in the crowdfunding game, then, will be the innumerable small businesses that fall somewhere in between. They’ll be startups and young businesses that have growth potential, but not on a large enough scale to attract venture capital: the environmentally friendly flip-flop maker in Seattle; the custom candy maker in Boise, Idaho. Mobile-gaming startups, especially those outside Silicon Valley, are also prime candidates, says Bill Clark, who runs an Austin firm called MicroVentures that connects tech startups to angel investors. They may be too risky a bet for the banks but perfect for small-time investors, who are willing to lose a few thousand dollars for the chance of a big return—or just to support a business they admire and might even use. In short, they’ll be the type of startups that already attract donors on crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter—only now the money will flow more readily, because the donors stand to gain as well. (As of now, Kickstarter projects can only offer nonmonetary perks to those who contribute.)

Along with individual companies, small-time startup scenes outside of Silicon Valley are likely to reap rewards as well. Austin, Boston, and New York have had some success in building startup cultures, but they’ve been held back by the Bay Area’s grip on venture-capital money. Crowdfunding will allow companies without access to Sand Hill cash to find the capital they need online, perhaps spurring a wave of innovation among mom-and-pop startups whose ambitions are local rather than global. If that happens, the JOBS Act might end up creating some jobs after all.