The old conventional wisdom about Microsoft was that you could never count it out. Sure, the company would always break into new markets with products that looked dead on arrival—see Windows 1.0 or Internet Explorer 1—but Microsoft’s genius lay in its persistence. When Bill Gates got hold of an idea—conquering desktop computing, controlling the front door to the Web—he turned into a nerdy Wile E. Coyote, constantly inventing new ways to go after his rivals. In Version 2, he’d fix 80 percent of what was wrong with his first effort, and in Version 3 he’d fix 80 percent of Version 2, and so on. He’d never reach perfection this way, but Gates was never interested in perfect: By the time Microsoft reached Version 4 or 5, it was usually halfway decent. And when Gates found something halfway decent, that was usually the end of the game for everyone else. (He had a better track record than the coyote in that respect.)

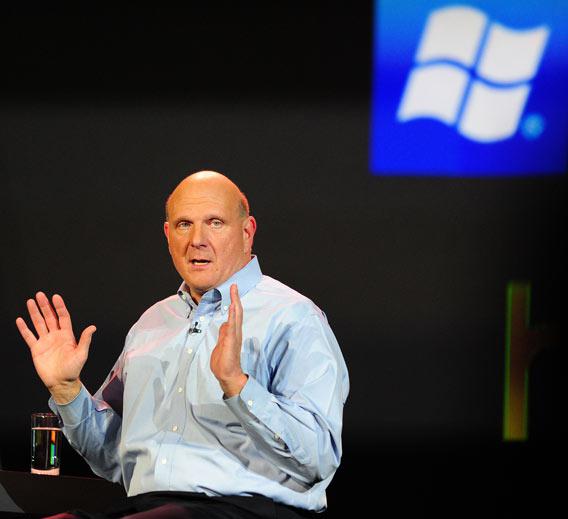

Then Gates left, Steve Ballmer took over, the Internet became the dominant force in the tech business, Apple hit a string of home runs, and the old conventional wisdom began to fail. Over the last decade, Microsoft tried a half-dozen initiatives to enter the music business, but nothing worked. It suffered the same fate with search engines: Bing is better than all its previous search efforts and it keeps improving, but nobody cares. Windows and Office, its two biggest products, are tied to a model of computing that looks to be on the wane. And with the exception of the Xbox, Microsoft’s recent products seemed to demand a new conventional wisdom: Whatever it does, count Microsoft out before it even gets started.

But not anymore. Maybe.

I’ll say it: I’m bullish on Microsoft in 2012. This could be the year that it shakes its malaise and takes its place alongside Apple, Google, and Amazon as a dominant innovator of the mobile age. For the first time in forever, Microsoft has a couple major products that are not merely good enough. They’re just plain great. I’ve been effusive in my praise for Windows Phone 7, Microsoft’s new mobile operating system. At the Consumer Electronics Show this week, we saw the one piece that has been missing from Microsoft’s new phone effort—killer hardware. Nokia unveiled the Lumia 900, the most powerful and beautiful Windows Phone to hit the United States yet (it will be released on AT&T sometime this year). Then there’s Windows 8, the spectacular desktop OS that Microsoft plans to release this year, and which will feature a new mobile-friendly touch interface that could make for the first viable Windows competitors to the iPad.

If you consider Microsoft’s Xbox juggernaut, which now features not just games but lots of entertainment apps, you begin to see the outline of a strategy to win big. Here’s a company with a killer mobile and desktop OS, a place in hundreds of millions of offices and living rooms around the world, a great design team, an unbeatable sales and distribution arm, and billions in cash. When you put it that way, Microsoft almost sounds as good as Apple, doesn’t it?

I’ll admit that this is all more than a bit speculative. There are many reasons why Steve Ballmer will have a hard time re-enacting the comeback strategy of Steve Jobs, and I’ll get to a few of them below. But first let me dismiss one of the main knocks on Microsoft—that it is getting its act together “too late.” This line of thinking—argued most cogently by MG Siegler—says that Apple and Google are so far ahead in the mobile business that Microsoft’s only hope is to release phones or tablets that blow the market away in the same way the iPhone did in 2007. If Microsoft’s gadgets are only as good as or even just slightly better than its competitors’ stuff, developers won’t create apps for it, and customers won’t buy phones that lack apps.

I think such agonizing over apps is overblown. There are now more than 50,000 apps in the Windows Phone Marketplace, which is more than enough for most people; as customers get hooked on new Windows hardware, app makers are sure to create even more, in the same way they flocked to Android when that platform began to look viable.

In general, “too late” isn’t much of a problem in the tech business anymore, because the Internet has allowed both customers and developers to move between platforms without much hassle. That’s why the Mac OS is seeing a resurgence after years of being pummeled by Windows, why Gmail and the Chrome Web browser succeeded even though they were years behind their competitors, and why Android now commands nearly half of the smartphone market. In today’s tech business—especially in mobile, where people pick up new phones as often as they do new shoes—companies have many chances to make a first impression.

If Microsoft fails now, it’ll be because of two other shortcomings. First, it relies on third-party hardware makers to get its software to the masses. And second, it still derives most of its money from desktop PCs. When Steve Jobs came back to Apple in the 1990s, he had nothing to lose. He could scrap Apple’s OS and replace it with something new, push the firm into mobile devices, and open physical and digital stores. Sure, some of this seemed crazy, but what was the harm in trying—Apple was nearly bankrupt anyway. And then, when he decided what he wanted to do, Jobs could control the experience entirely. He didn’t have to wait around for Dell or HP to make great laptops worthy of his new OS. He could do it himself.

Steve Ballmer, meanwhile, does have a lot to lose. Microsoft made $70 billion last year, and almost every penny came from the desktop computing business. Ballmer has to somehow shift his company’s focus to the far less remunerative mobile business without abandoning his main source of revenue. This will likely lead to unfortunate compromises. For instance, Microsoft hasn’t yet said whether it will let today’s Windows programs run on Windows 8 tablets. Jettisoning the old apps would be the right decision; no program developed for the desktop interface is going to work very well on a tablet, and trying to blend the two interfaces will turn Windows tablets into a neither-fish-nor-fowl mess. But Microsoft has always prided itself on backward compatibility; the fact that your old programs work on new versions of Windows is the cornerstone of its empire. Is it tough enough to go back on that promise now?

But even if Ballmer does make the right technical decisions, he still depends on hardware makers to build great gadgets. He’s got reason to be optimistic: In addition to Nokia, we saw Intel and Vizio (the TV maker that’s now pushing into the PC and tablet business) unveil some great-looking Windows devices at CES this week. As I’ve warned before, CES can be a parade of vaporware: We’ll see over the course of this year how many of these phones, tablets, and ultra-thin laptops are actually released, and then we’ll see how well they work. But if the stars align—and isn’t it time they did?—2012 could well mark Microsoft’s return.