Steve Jobs hated the stylus. It’s obvious why: controlling your mobile device with a penlike thing meant having to carry something extra, and Jobs always disdained extra things. “God gave us 10 styluses—let’s not invent another,” he used to say, according to Walter Isaacson’s biography.

The stylus was one of the reasons Jobs killed the Newton, Apple’s 1990s-era mobile personal assistant. It was also one of the reasons he decided to build the iPhone and the iPad. A decade ago, when Microsoft was pushing its vision for tablet machines, Jobs considered Bill Gates’ love of the stylus a key vulnerability. “As soon as you have a stylus, you’re dead,” he said. In 2002, after hearing a description of Microsoft’s tablet, Jobs marched into his office and issued an order: “I want to make a tablet, and it can’t have a keyboard or stylus,” he said. “So could you guys come up with a multi-touch, touch-sensitive display for me?”

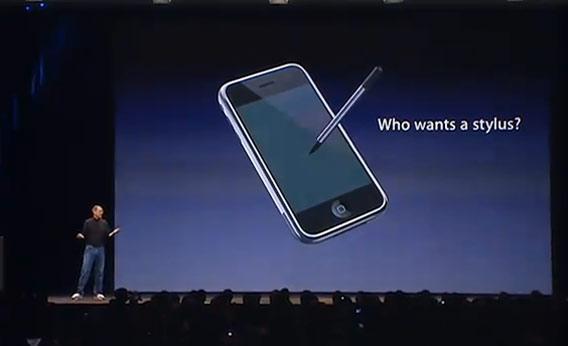

And that was it—the moment the stylus died for good. Over the next few years, Apple worked in secret to perfect touch computing, and with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007, Jobs sought to make the touchscreen the signature digital interface of our era. “Who wants a stylus?” he sneered at his Macworld keynote unveiling the phone. “You have to get ‘em, put ‘em away, you lose ‘em. Yech! Nobody wants a stylus. So let’s not use a stylus.”

I used to think Jobs was right. The PalmPilot, the only stylus device I’ve ever owned, was a great little machine, but I did find its stylus to be a hindrance. Because it didn’t have much of a processor, the PalmPilot couldn’t recognize normal handwriting. Instead you had to learn Graffiti, a strange script that helped the machine figure out what you were writing—and only confirmed Jobs’ argument about styluses being fussy. Worst of all, the stylus meant that I always needed both hands to operate the Palm, one to hold the device and the other to point. That’s a fatal flaw: a small, ultraportable device like a personal assistant or a phone needs to be useful even if you’ve only got one hand, and that’s impossible with a stylus.

But just because the stylus doesn’t work on a phone doesn’t mean it won’t work anywhere else. Lately, I’ve discovered that the stylus can be a perfectly useful and sometimes even transformational doohickey. Indeed, despite Jobs’ banishment, there seems to be a brisk business in styluses for use with the iPad, and there are several apps that are optimized for these pseudo-pens. (These are called “capacitive touch” styluses—ones that make the kind of electrical connection your finger would. It won’t work if you use, say, a Popsicle stick.)

I’ve been playing with a few of them over the last few days, and to my surprise, I’ve gotten fired up about the possibilities of the humble, misunderstood, underappreciated stylus. For certain uses, the stylus is way better than fingers—it’s more precise, easier to control, and more capable. A stylus lets you type just as fast (and maybe faster) than you can with your finger on a touchscreen and it allows for fine-motor skills like drawing and photo editing. Jobs wondered who wants a stylus. I do! And if tablet and app makers took some time to optimize their product for styluses, you will, too.

Today, people use styluses on iPads for specialized, pen-specific tasks like sketching. That suggests another obvious place for the stylus: writing. Though handwriting recognition has advanced enormously since the days of the Newton and the PalmPilot, writing on a screen still gets a bad rap. That’s probably because the most common use for styluses these days is on credit-card payment machines, and those devices are terrible at capturing your signature.

The handwriting apps I used on the iPad were much, much better than those credit machines. Using a stylus that cost a little more than $2 and an app called 7notes, I was able to write several lines that were instantly transformed into text. The app wasn’t perfect; sometimes it misinterpreted what I was writing (I have terrible handwriting). Like a standard touch keyboard, though, it offered error-correcting suggestions that improved my speed.

Research suggests that people type on an iPad at about 45 words per minute, which is about two-thirds as fast as we can type on a standard keyboard. People handwrite even slower—about 30 words per minute—but handwriting is also more flexible: It’s easier to enter stuff like equations and arrows and smiley faces that you can’t find on a standard keyboard. If you’ve ever tried to take lecture notes on an iPad (or a laptop), you’ll immediately recognize this difficulty.

“The research shows that the type of content you produce is different whether you handwrite or type,” says Ken Hinckley, an interface expert at Microsoft Research who’s long studied pen-based electronic devices. “Typing tends to be for complete sentences and thoughts—you go deeper into each line of thought. Handwriting is for short phrases, for jotting ideas. It’s a different mode of thought for most people.” This makes intuitive sense: It’s why people like to brainstorm using whiteboards rather than Word documents.

Today’s touch devices cater to the first, deep mode of thought, but—lacking a stylus—they don’t give us a way to jot down our nonlinear ideas. That’s why I sometimes find it more frustrating to read e-books than paper books—I can’t quickly mark up a Kindle title by underlining, highlighting, or writing notes in the margins. The best example of such marginalia—see David Foster Wallace’s—are freeform doodles, as graphical as they are textual. You can’t do that kind of thing with a keyboard.

Now, I should make clear that I’m not calling for stylus-only devices. The best hope for the stylus is that it takes its place alongside your fingers on a device that accepts both touch and pen-based inputs. For example, see this prototype that Hinckley designed:

There are some amazing things in that video, though at first glance much of Hinckley’s demo might seem a bit obvious. That’s the point: When you combine a pen and your fingers, you can get a digital interface that closely resembles how we interact with objects in the real world. Notice, for instance, how Hinckley holds down a photo with his finger, and then cuts out an image from the photo using his pen. That’s exactly the motion you’d use in real life—and to do something similar without a pen, you’d probably need to do something extra (like zoom in on your image in order to make a precise crop with your fat finger).

The stylus, then, should have obvious appeal in this unjustly pen-free era. But what about Steve Jobs’ main argument against the stylus—it’s something extra to carry and get lost, and who wants that?

If device makers began to take the stylus seriously, I think we’ll get over the hassle. For one thing, you could make the same argument about pen and paper, but nobody ditched handwriting because we were always losing our pens. More importantly, all great tools represent something extra to carry and protect, and you’re always making a trade-off between the hassles of investing in that tool and the utility you’ll gain from it. Considering all the things we carry around with us these days—phones, tablets, power cords, cameras, memory cards—it’s irrational to fault the stylus alone. A stylus is small and cheap; if you lose it, you’ll be able to get a new one in a snap for just a few bucks. Hey, it’s a lot better than having to replace an iPad.

Jobs was famously single-minded. When he found something he loved, he loved it everywhere, and when he identified something he hated, he hated it forever. But he took his hatred of the stylus too far. God gave us 10 fingers, and they’re not the same as pens. We’d get a lot more done if we used some of those fingers to pick up a stylus.