Two twentysomethings hop out of a cab. They get dinner. They grab drinks at a bar. Neither stops to worry about splitting the tab. “Just Venmo me,” one says.

That’s how most stories about Venmo, the popular mobile-payment app, begin. First there’s a short anecdote illustrating how Venmo is fast, casual, convenient, and trendy. There might be a moment of conversion: At first, one of those twentysomethings is nervous about sending real money through a mobile app, but after trying Venmo and witnessing its amazing ease and speed, he becomes a proponent of the service as quickly as Venmo became a verb.

This is not one of those stories. It starts, instead, with Chris Grey, a 30-year-old Web developer in New York City, waking up last Thursday to a notification from Chase bank that his account had a pending transaction involving a large sum of money. At first glance, he thought his tax refund must have come through. He’d already paid his rent for the month, so he figured the alert must be for an incoming amount. “Then I did a double take,” he says.

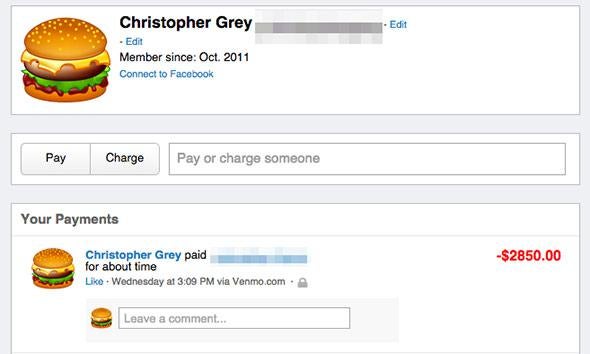

Chase had pinged Grey not about a credit to his account, but a debit for $2,850, through Venmo. Confused, Grey tried to pull up his Venmo account, but his password no longer worked. He used the reset option to get in, then inspected his settings. Under email authentications, a new address appeared. Notifications were disabled. Grey’s payment history showed that the funds—slightly below Venmo’s weekly sending limit of $2,999.99—had been sent at 3:09 p.m. the day before to a user he didn’t recognize. Some text listed the transaction’s ominous-sounding purchase: “for about time.”

Clearly, something was wrong—yet Venmo hadn’t notified Grey that anything suspicious could be going on. “I never got an email that my password had changed, that another email was added to my account, that another device was added to my account, or that a lot of my settings had changed,” he says. A colleague and I were able to duplicate this lack of notification with a quick test: Venmo doesn’t alert you if your password or email credentials change from within the account. “There are basic security holes that you could drive a truck through,” Grey says.

These shortcomings should be concerning for any service that handles sensitive financial information, but particularly so for Venmo, which has set its sights on becoming the dominant mobile app for peer-to-peer financial transactions in the United States. In the third quarter of 2014, Venmo processed $700 million in payments—nearly five times the transaction volume it did in the same period a year earlier. Venmo doesn’t share its user numbers, but eBay chief executive John Donahoe has dropped hints. “Venmo is on fire,” he said last month during eBay’s fourth-quarter earnings call. “If you go to any college campus across America, they talk about Venmoing money to each other.”

By making the money transfers quick, uncomplicated, and even cool, Venmo is winning. But for all its promise as a smooth and efficient financial service, Venmo’s popularity seems to be outpacing its customer-support capabilities. As of November, Venmo only had around 70 full-time employees. (Its parent PayPal, which oversaw $64.3 billion in transactions in the last quarter of 2014, has more than 10,000.) Three years after the service left its beta phase, Venmo doesn’t have a dedicated phone line for customer issues. Urgent emails about stolen funds receive slow responses. It doesn’t offer two-factor verification, an increasingly common security layer that requires users to provide a secondary passcode to access an account, though it’s working to implement it. Venmo says its mobile-transfer infrastructure “uses bank-grade security systems and data encryption to protect you and guard against any unauthorized transactions and access to your personal or financial information.” But when a hacker who breaches an account using your password can send $2,850 as quickly and conveniently as a twentysomething can repay $7 for a burrito, that’s clearly not enough.

“These are big problems,” says Rob Shavell, co-founder and CEO of Abine, a data-privacy firm that helps users secure personal information. “There ought to be email warnings, there ought to be two-factor authentication. It’s true for us, it’s true for Venmo, it’s true for all these services.”

Courtesy of Chris Grey

Venmo did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Lisa Kornblatt, a spokeswoman for Braintree, the company that acquired Venmo in 2012 and was subsequently bought by PayPal in 2013, on Monday pointed me to PayPal’s security and privacy policies, and didn’t respond to further inquiries. Venmo also declined to speak with me when I stopped by its New York headquarters (which happens to be located one floor above Slate’s office), directing me instead to email press@venmo.com.

Once he realized his account had been hacked, Grey contacted Chase first. To his horror, the bank informed him he’d need to close out the account. Because he’d linked Venmo to his Chase routing number—rather than to a debit or credit card—the account, which he’d had since college, was irreversibly compromised. That meant, in the short term, no access to his money. Grey got to work filing a claim with Chase to dispute the $2,850 withdrawal.

If nothing else, dealing with fraud is something banks are very good at. They have fraud departments to handle problems like Grey’s, and dedicated hotlines for customers to call if something happens. One of the great promises of a credit card is the small customer service number printed on the back. Venmo doesn’t offer that level of assistance. You won’t find a phone number on the contact portion of its website. On the security page, the company advises customers who “suspect that there has been any unauthorized activity” to “contact us immediately at support@venmo.com—we’re here to help.” (You can also tweet @VenmoSupport.) What’s not noted on the security page—but is buried in section C, part 1, small letter n, roman numeral iv of Venmo’s user agreement—is that you should do this immediately, because if “you contact the Company within two Business Days after learning of the loss or theft, then your liability shall not exceed the lesser of $50.00 USD or the amount of unauthorized transfers that took place on your account before you provided notice to the Company.” After two business days, your liability can jump as high as $500, per Venmo’s terms.

Grey says he went ahead and contacted Venmo almost immediately after learning of the unauthorized activity and reaching out to Chase, at first via the company’s online contact form and then to support@venmo.com. Grey provided Slate with email correspondence showing that he first wrote to the support email address at 11:55 a.m. on Thursday, then again at 6:50 p.m., 7:43 p.m., and finally at 9:38 a.m. on Friday. More than 24 hours after he first contacted Venmo, Grey was still waiting.

Grey isn’t the only one to report an experience like this. Peruse replies to the @VenmoSupport Twitter feed and you’ll find plenty of users complaining that the company has not answered their emailed requests for assistance. One of those frustrated users, Mohsin Charania, a professional poker player, told me a story similar to Grey’s. In December, Charania says, his account was hacked for more than $2,000. The email and password associated with the account were changed, though he was never notified of any resets, and he had to use the “forgot password” option to regain access. Charania says he filled out Venmo’s “Contact Us” support form and waited, but hours passed without any response. The next morning, “I tweeted at support, and I was like, this is ridiculous,” he says. “I have a friend who writes for Huffington Post, and he tweeted at them too being like, this is very scary, that you’re a financial services company, and someone could get hacked and you’re not around to help them.” Shortly after calling Venmo out publicly on Twitter, Charania finally got an answer, and the company eventually reimbursed him.

For many Venmo users, the most disconcerting thing about these tales should be that what happened to Grey and Charania could just as easily happen to you. I don’t link my Venmo account to anything—I simply try to maintain a balance of around $30 that I can use to pay friends and co-workers for small things as needed. I’m almost certainly an outlier. Most people connect their Venmo account to either their debit card, credit card (the only nonfree option, with a standard 3 percent fee), or directly to their bank accounts. This is what Venmo wants. The company’s ultimate vision, as Braintree CEO Bill Ready told Bloomberg in November, is to build a user base so large that Venmo becomes a default mobile checkout option at stores, and can charge merchants for the privilege of accepting Venmo payments.

To create such a network, Venmo has gone to great lengths to make its sign-up process as easy as possible. Late last year, it added features that let iOS and Android users who downloaded the Venmo app link it directly to their bank accounts using their existing online-banking credentials. This more “frictionless” process, as Fast Company dubbed it, eliminated the previous need for users to manually enter their bank routing information into the app. Venmo has also marketed itself not just as a finance app, but as a social one. Sign up for a Venmo account and you’re immersed in a feed of your friends’ public transactions. Bruce paid Joe for pizza. Abe charged John for IKEA furniture. Henry paid Julie for coffee. To be on Venmo, as a Matter article succinctly put it in July, is to take part in “public displays of transaction.”

Of course, what gets lost in all this—in the streamlined interface, simple onboarding process, and social pressure to join a service that lets you pay friends with a quick tap—is a sense of the trade-offs. The last three steps on Venmo’s six-part “Getting Started” checklist prompt new users to “Link your bank,” “Add a card,” and “Increase your spending limit.” If you ranked the risk of those options from lowest to highest, “it would certainly be credit card, then debit card, then the routing number,” says Matt Schultz, senior industry analyst at CreditCards.com. At no point does Venmo indicate this—in fact, by requesting a bank account before a card, it might even be encouraging users to take that riskier route.

The defining social quality of Venmo’s platform also creates unique security challenges. Last May, three students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology noted in a paper that Venmo’s interface and social-networking component made it vulnerable to “social engineering attacks.” Because Venmo doesn’t distinguish visually between a user’s friends and others on the app, a benign payment request from a hacker might not immediately stand out. More importantly, since Venmo users can quickly change things like their name and profile picture, it’s easy for hackers to impersonate users’ actual contacts and trick them into sending money to the wrong accounts.

“I know tons of people that use it and I thought it was safe,” Grey says. “But with something that has your bank account number and your routing number, that’s super personal and I don’t think that’s an option that should even be there.”

A day and a half after he first discovered the fraudulent transaction and contacted Venmo, Grey finally got a response. The email, sent from “Michael” from Venmo’s “Fraud & Risk” department, outlined basic steps he should take to protect the account (change passwords, revoke access to unauthorized sessions, add a PIN), and said the company was “working to prevent this unauthorized account access in the future.” Grey emailed back and asked the representative to cancel his account. Many of his friends and colleagues are doing the same.

Chase, for its part, reimbursed Grey’s money last Friday morning. “I thought I would have like no money for the weekend,” he says. Once the fix came through, “I was able to buy lunch.”