Virtual reality may be one of the most important technologies in our future, producing a great leap forward in many fields. While most people now focus on VR’s use in entertainment areas, its real impacts will be in the arts, business, communication, design, education, engineering, medicine, and many other fields.

That’s from an article published in a magazine called the Futurist in 1996. At the time, it didn’t seem far-fetched. Virtual reality was everywhere in the mid-’90s, from Nintendo game systems to Hollywood movies to Jamiroquai songs. At least, the idea of it was.

In practice, however, virtual reality machines fizzled. Limited by slow processors and crude motion-tracking sensors, engineers couldn’t deliver on the promise of a genuinely transporting experience. And on the software side, developing interactive 3-D worlds proved daunting. A Google Ngram search shows that the buzzword’s popularity peaked in 1998 and headed downhill. Virtual reality, it seemed, was a technological dead end.

Or was it? In 2012, a startup called Oculus announced plans for a “truly immersive virtual reality headset for video games,” and its Kickstarter campaign raised $2.4 million in a matter of days. Two years later, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg announced that his company was buying Oculus VR for $2 billion. Now Sony and Samsung are building VR headsets of their own, and Oculus founder Palmer Luckey is on the cover of Wired. Virtual reality, the caption promises, “is about to change gaming, movies, TV, music, design, medicine, sex, sports, art, travel, social networking, education—and reality.” Oh, is that all?

This might sound like an exceptional tale of a technology that suffered a dramatic fall from grace, laid dormant for years, and then made an improbable return to glory. But it isn’t the exception, says Jackie Fenn, vice president of Gartner, a technology research firm. It’s the rule.

Examine the formative history of almost any major technology that has caught on in the past century, she says, and you’ll discern a similar pattern. First there’s a breakthrough, which generates hype and attracts early adopters and evangelists. Then the media catches on, clutching for superlatives to convey the wondrous future that will soon be at hand. Businesses smell an opportunity and jump on board. The mainstream public’s embrace awaits.

But hype moves faster than progress. To turn a groundbreaking idea into magazine covers, speaking engagements, and buzzwords might take a few months. To turn it into a well-oiled consumer product can take years, or even decades. Disappointed with the results of early prototypes and hungry for a fresh narrative, the same media that hyped the technology turn against it. The public grows cynical. The businesses that were quick to adopt the technology are just as quick to drop it. And the early adopters move on to the next thing. (Kozmo.com, anyone?)

Yet if the technology truly holds promise, Fenn says, it usually doesn’t die. Somewhere, in a tinkerer’s garage or a well-funded lab insulated from market pressures, engineers continue to work on it. They learn from mistakes and gain a more realistic perception of the technology’s strengths and limitations. Eventually, the idea resurfaces and achieves mainstream acceptance.

Fenn calls it “the hype cycle.” Here’s what it looks like:

Fenn is convinced that the cycle is more or less predictable and can be applied to business strategies as well as emerging technologies. Her 2008 book Mastering the Hype Cycle mentions customer loyalty cards, e-commerce, and the idea of “business models” as textbook examples. Each enjoyed a surge of hype, followed by a backlash and retrenchment, before reaching the plateau.

Building on Fenn’s work, Gartner has begun publishing annual “hype cycle” reports that track various trends’ progress along the S-curve. The implication is that we can predict which are bound for a fall and which are due for revitalization. The firm’s 2010 report, for instance, correctly pegged 3-D flat-panel TVs as overhyped. Its 2013 update foresaw the same for big data, gamification, and consumer 3-D printing. Enterprise 3-D printing, however, had progressed to the slope of enlightenment while speech recognition was approaching the coveted plateau at last. (I happen to agree.)

Appealing as the model is, however, the path to progress isn’t always quite so predictable. Some technologies, like the World Wide Web, hit relatively minor bumps on the fast track to global ubiquity. (Remember when Newsweek pooh-poohed its prospects in 1995?) Others, like virtual reality, suffer such severe setbacks that they enter long periods of hibernation before re-emerging.

And as Matt Novak, editor of Gizmodo’s Paleofuture blog, points out, some of the high-tech futures we’ve been promised over the years never quite materialize—at least, not in the form their initial purveyors had in mind.

Sometimes, as with the videophone that Bell Labs introduced in the 1960s, it’s at least partly because they don’t fit the existing infrastructure. The same could be said of electric cars. They had a heyday in the early 20th century, but as roads improved, they gave way to gasoline-powered cars with a greater range, and we ended up with a national network of gas stations rather than charging stations.

To say that neither idea rebounded quickly would be an understatement. Then again, they never quite died. Nearly a century later, electric cars are making a comeback, having been reimagined as sleek luxury vehicles. The videophone resurfaced as a standalone gadget in a 1993 AT&T promotional video, but it still looked a lot like the home phones and payphones of the day. In the end, Novak notes, “the videophone snuck up on humanity”—not as a piece of hardware, but as software (think Skype and FaceTime).

Virtual reality, Novak suggests, has undergone a similar metamorphosis. Look around a crowded room, and you won’t see a bunch of people wearing VR headsets. Instead, you’ll see them peering into tiny screens, through which they lead digital lives replete with usernames, avatars, remote colleagues, and virtual friends.

Now, it seems, the headsets may be coming back, too. But are they on the slope of enlightenment, or is this just the start of a second hype cycle? Fenn couldn’t say for sure.

I doubt that anyone can. If you zoom out far enough, the hype cycle starts to look less like a single, discrete process and more like a never-ending ebb and flow.

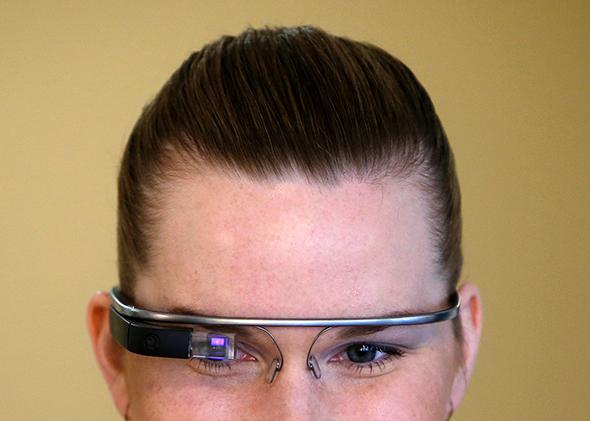

But this much we know: Today’s futuristic tech trends, from Google Glass to big data to MOOCs, will face setbacks. They will be mocked, they won’t work as planned, and people expecting an immediate revolution will be disappointed. And yet we also know that this won’t spell the end of wearable technology, data analysis, or online education.