Much of today’s technology is powered by software that developers share freely. The leading Web server software (Apache), the leading smartphone operating system (Android), and most of the code of the leading Web browsers (Chrome, Firefox) are open source. Some people see these developments as evidence of a sharp break from the past: We have entered the Age of Open Innovation, in which inventors no longer keep their knowledge secret or locked up with patents.

But, in fact, innovators shared knowledge extensively in the past. True, many textbooks and technology museums paint pictures of historical inventors jealously guarding their secrets. The Wright brothers, for instance, refused to let anyone see their airplanes fly for several years after their success at Kitty Hawk until they obtained a patent. But scholars have established that past inventors frequently shared their inventions and cooperated with one another in developing new knowledge. Indeed, prior to Kitty Hawk, even the Wright brothers freely shared the results of their experiments and their designs with an international network of aviation developers who had been exchanging knowledge for decades.

This was hardly unusual. Historians have documented that inventors shared ideas and designs in many key technologies. In 19th-century Britain, those include blast furnace technology for making iron, the high pressure steam engine in the Cornish mining district, textile equipment, the development of coal burning houses in London, and advances in civil engineering. During the same period in the United States, innovators shared designs and other knowledge in the cotton textile industry, in the high-pressure steam engine for western steamboats, in papermaking, in the Bessemer process for making steel, and among mechanics generally. In addition, American and British farmers swapped ideas frequently, including methods of crop rotation and extensive biological innovation in wheat, cotton, tobacco, alfalfa, corn, and livestock.

However, few of these episodes lasted more than a couple of decades. Shared innovation gave way to firms seeking to lock up their knowledge. And therein lies a possible warning for today’s innovators.

People often assert that patents are essential to protect small inventors from imitators. Without patents, new ideas will be quickly imitated, competition will drive down prices, and the original inventor will not be able to profit. But the inventors who shared their ideas actively encouraged imitation, at least initially. Why?

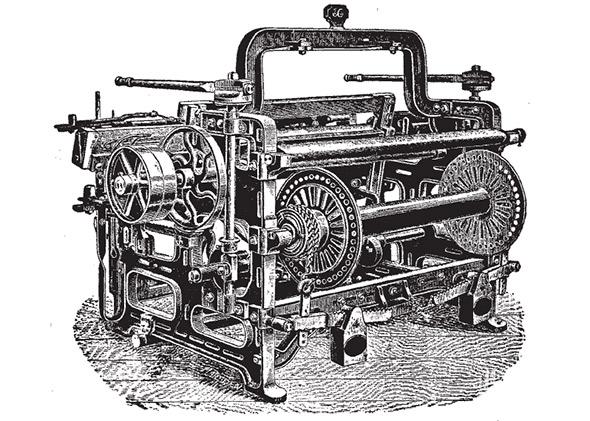

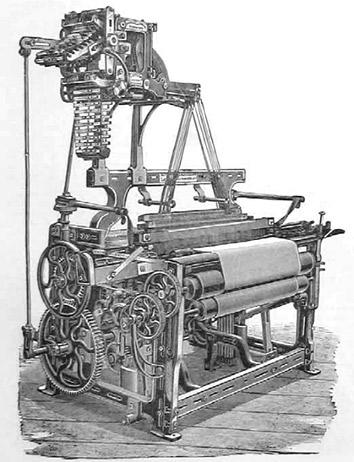

The case of the power loom demonstrates the arc nicely. The power loom, which partially automated textile weaving, was one of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution. The most successful design in the U.S. was built by a Scottish mechanic, William Gilmour. He was contracted to design a power loom for Judge Daniel Lyman, who ran a textile mill in Rhode Island. The loom and associated equipment went into operation in 1817, and with Lyman’s encouragement, Gilmour made his design freely available to other mechanics.

Image courtesy Textile Mercury/Creative Commons

Although Gilmour and Lyman directly helped competing mechanics and textile mills, they weren’t fools. For two decades, machine shops and textile mills made high profits. Machine shops could charge high prices for textile equipment because few mechanics knew how to build them; textile mills could make high profits because it was much cheaper to use the new loom. Imitation didn’t substantially reduce profits because there was a shortage of mechanics who could build the machines, of entrepreneurs who could run the new type of enterprises, and of skilled workers who could make the new contraptions productive.

At the same time, there were significant benefits to sharing knowledge. Gilmour might have the best loom design, but many other mechanics had better designs for some of the other devices used to produce cloth. In addition, mechanics continually made improvements. By exchanging ideas for two decades, the textile equipment mechanics rapidly improved the technology, doubling the cloth a weaver could produce in an hour compared to the first power looms.

Most of the important weaving inventions during this time were not patented. Because imitation did not destroy profits, it simply didn’t pay to use patents. (This wasn’t limited to the loom: Only 15 percent of the U.S. inventions shown at the 1851 World’s Fair in London were patented.)

But after the 1830s, almost all significant weaving inventions were patented. The textile mills still exchanged information about best practices, but critical knowledge was more often protected by secrecy or patents. Conditions had changed. There no longer were shortages of skilled mechanics, managers, and workers. Market competition was fierce, and profit margins shrank for the textile mills and machine shops.

We see the same thing in other technologies, such as Bessemer steel in the United States or the steam engines in the mines of Cornwall, England: During the early stage of a major new technology, inventors share designs and knowledge and patent little; later, things become more competitive and patents play a larger role. As technologies mature, firms share less and patent more.

Something similar is apparent today. Apple Computer got its start in the Homebrew Computer Club, where members shared designs and product features every two weeks or so. During its first decade, the company obtained just 14 patents, mostly on very specific features. And, of course, Apple benefited greatly from this sharing. As Steve Jobs famously declared, “[W]e have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.” These included the idea of the graphical user interface, the MP3 player, and the tablet, which Apple borrowed and improved. Today, Apple is a bit different. In 2012 it obtained 1,236 patents, and during recent years it’s initiated more than 100 patent lawsuits around the world, pursuing “thermonuclear war” against the Android phone makers.

This pattern is seen with other companies, too. Microsoft did not obtain its first patent until 1986, when it was 11 years old. Today it has more than 20,000 patents and actively enforces them. Qualcomm also has a large patent portfolio and is fighting anti-patent-troll legislation in Congress. But the founders of Qualcomm freely shared their technology during the early years of digital wireless technology, including a decoding algorithm widely used in cellphones today.

There are still plenty of areas where innovators develop new ideas and share them. Most software startups today, for example, do not patent, although more are doing so for defensive reasons. But history should remind developers that what is shared today might not be tomorrow.