Also in Slate: Jonas Salk didn’t patent the polio vaccine, but Google Doodles—like today’s on Salk—are patented.

On April 12, 1955, Edward R. Murrow asked Jonas Salk who owned the patent to the polio vaccine. “Well, the people, I would say,” Salk responded. “There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

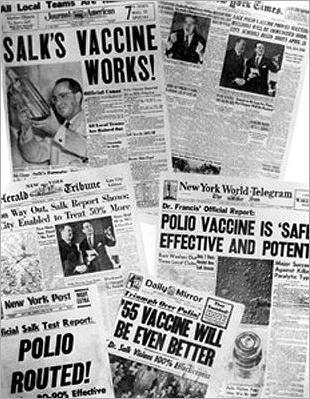

By the time of his chat with Murrow, which aired on the day the polio vaccine was announced as safe and 90 percent effective, Salk was already more messiah than virologist to the average American. Polio paralyzed between 13,000 and 20,000 children annually in the last pre-vaccine years, and Salk was the face of the inoculation initiative. Appearing on television to present the vaccine as a gift to the American people was a public relations masterstroke.

Over the last half-century, Salk’s rhetorical question to Murrow has become a rallying cry for those who campaign against pharmaceutical company profiteering. To many, it represents a generous view of scientific discovery distilled down to a beautiful simplicity. One critic of the big pharma called Salk “the foster parent of children around the world with no thought of the money he could make by withholding the vaccine from the children of the poor.”

In fact, Salk’s three-sentence response to Murrow is a dangerous intuition pump—a misdirection from complex questions. It represents an easy but wrongheaded way to avoid the messy work of constructing a system to incentivize medical breakthroughs and make them widely available in the context of 21st-century economic realities. That’s not to say Salk was a propagandist or a panderer—he probably meant every word he said. But his thoughts on the polio vaccine applied to a specific situation at a specific time in our history.

It helps to break Salk’s famous quote into two distinct claims: First, he argued that the polio vaccine belonged to the people. Second, he posed the rhetorical question comparing a vaccine to the sun.

The first claim is nearly indisputable as it applies to the polio vaccine itself, because the public voluntarily funded the vaccine’s incredibly expensive research and field testing.

“People worked on the polio vaccine like it was the Normandy invasion,” says Jane Smith, author of the book Patenting the Sun: Polio and the Salk Vaccine. More than 650,000 children were vaccinated. Their doctors had to submit forms, and public health officials tracked the information. Then it all had to happen again for placebo and control groups.

In the single year that the polio vaccine was unveiled, 80 million people donated money to the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which spearheaded the vaccine effort. Many donors could only afford a few cents, but gave anyway (hence the foundation’s modern name, the March of Dimes). Schools, communities, and companies joined in a remarkable display of unity against the disease. Even Walt Disney’s cartoon characters contributed their talents, appearing in a film that adapted the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ song “Heigh Ho” to an anti-polio ditty. In the 13 years leading up to the vaccine’s roll out, the budget of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis swelled from $3 million to $50 million. An entire generation of microbiologists received money from the foundation, which even played a role in Watson and Crick’s description of DNA.

There was near unanimity within the organization that the public had already paid for the polio vaccine through their donations, and patenting it for profit would have represented double charging. That’s what Jonas Salk should have said to Murrow—not that all vaccines belong to the people, but rather that this vaccine belonged to the people.

There is an important footnote regarding Salk’s statement that “there is no patent.” Prior to Murrow’s interview with Salk, lawyers for the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis did look into the possibility of patenting the vaccine, according to documents that Jane Smith uncovered during her dive into the organization’s archives. The attorneys concluded that the vaccine didn’t meet the novelty requirements for a patent, and the application would fail. This legal analysis is sometimes used to suggest that Salk was being somewhat dishonest—there was no patent only because he and the foundation couldn’t get one. That’s unfair. Before deciding to forgo a patent application, the organization had already committed to give the formulation and production processes for the vaccine to several pharmaceutical companies for free. No one knows why the lawyers considered a patent application, but it seems likely that they would only have used it to prevent companies from making unlicensed, low-quality versions of the vaccine. There is no indication that the foundation intended to profit from a patent on the polio vaccine.

The decision not to patent the vaccine made perfect economic sense under the circumstances. “The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis was a nonprofit, centralized research and development operation,” says Robert Cook-Deegan, who studies intellectual property and genomics at Duke University. “They didn’t need an incentive structure.”

Photo courtesy March of Dimes/Wikimedia Commons

That brings us to Salk’s grand question: Can you patent the sun? When you unpack this query, which is really a policy argument, you find two assumptions. Most obviously, Salk assumed that a vaccine is a naturally occurring phenomenon rather than a human invention. In addition, and perhaps more importantly, he implies that this distinction should be central in patent law. Both of these points are debatable.

Whether a vaccine should be viewed as a naturally occurring substance, rather than a product of human engineering, may depend on the details of the individual inoculation. In 1796, Edward Jenner immunized an 8-year-old boy against smallpox by injecting him with pus from a milk maid who had been exposed to cowpox, a related disease. (The word vaccine comes from vaccinia, the Latin name for cowpox.) While ingenious, moving pus from one person to another would not entitle Jenner to a patent in modern America. Few modern vaccines are that simple, though. Some still contain live or dead cells from the pathogen itself, but others contain genetically modified versions of the virus or bacteria. Some rely on one or more proteins from the pathogen, or a part of a protein that’s sufficient to trigger an immune response. The flu vaccine, which has to be made anew every year, involves months of work by highly trained scientists working in state-of-the-art laboratories. It’s a stretch to describe modern vaccines as naturally occurring, even if parts of them are.

Although the U.S. government has issued thousands of patents related to vaccines, American jurisprudence is still in a state of confusion on this issue. The Patent Act of 1952, which established the current structure of patent law, did not recognize a difference between inventions and discoveries. When that distinction came from the Supreme Court in 1980, the court made clear that “products of nature”—like the sun, as Salk might say—are not patentable. Isolating and purifying a product, however, may render it patentable under the right conditions.

Should the Supreme Court ever get around to clarifying the patentability of vaccines, it may consider revisiting the distinction between discovery and invention, because it misses the point of intellectual property law: to incentivize research that will benefit humanity. Even if a vaccine is a product of nature, discovering that product and making it useful is absolutely nothing like discovering the sun and putting it to work. (Most living creatures have managed that trick on a daily basis for billions of years.) Since Jenner, few microbiologists have stumbled upon effective vaccines. Without the promise of exclusive marketing rights for some period, no profit-minded private entity would undertake the necessary research.

The landscape has shifted since Salk’s heyday. The U.S. government is now the primary applicant for vaccine-related patents, followed by GlaxoSmithKline and a number of other corporations. Private groups, like the Pasteur Institute, are also active. Responsibility for vaccine development is more evenly distributed now than in the 1950s, and that’s a good thing.

“There is no one solution,” says Cook-Deegan. “There will be a complicated set of solutions, including government, nonprofits, and private sector incentives. That’s the structure of innovation.”

At the end of his life, Salk helped found a corporation to develop an HIV vaccine. Although the vaccine eventually failed, Salk’s company moved to patent it in its early days of promise. The man who asked rhetorically when you could patent the sun eventually saw the light of financial incentives. There’s nothing wrong with that.