A month ago, I left my job at the San Francisco tech company that bought my advertising startup. I had loved building my company from the ground up, but after six years, I had big plans for my post-acquisition life. I was going to work out. I was going to explore San Francisco. I was going to spend more time with my girlfriend. I was going to meet people outside the startup bubble. I was going to learn something new and immerse myself in it.

It turns out there’s an app for almost all of that, and it is Pokémon Go. Since the game’s release less than a month ago, players have installed it on mobile devices an estimated 75 million times. Mark Zuckerberg plays Pokémon Go. Justin Bieber, too. While lots of users try the game and drop it, or just play it casually, across the country there’s a scene of hardcore players who’ve gotten truly, deeply hooked. I’m one of them.

For the past three weeks I played Pokémon Go like it was a job. I hunted its cute, cuddly creatures across 80 miles of beaches, parks, sidewalks, and playgrounds in San Francisco and New York. I tracked them on foot, bicycle, car, and pedicab. To my girlfriend’s simmering horror, I ran into wild coyotes, was chased off by security guards, and crashed a mysterious 2 a.m. playground gathering. I caught 141 of the 142 Pokémon available in North America.

Which brings me to my final Pokémon.

It’s just after midnight on a Sunday and I’m running down Fifth Avenue in New York City, arms pumping, iPhone clutched like a baton. I’m running like a man who doesn’t run very often. My shirt is translucent with sweat. I pass Trump Tower. I pass St. Patrick’s. I turn onto 47th. I have 32 seconds left. Two men I’ve never met shout encouragement and wave toward a growing crowd up the street. “She’s over there!” I huff and nod. I reach the throng and raise my phone.

With seconds to spare, I spot her. Time slows. She is big, beautiful, and pink, an ovoid vision with six dreadlocks that sway playfully as she hops back and forth. In her marsupial pouch she holds a gleaming white egg. She smiles at me. I smile back. Chansey. My prey. I am here to catch you. I tap my screen, and we face off: me, a 34-year-old newly unemployed tech entrepreneur with far too much time on his hands; she, a gentle, kindhearted cartoon character who is beloved by children worldwide, lays highly nutritious eggs, and is said to bring happiness to whomever catches her.

I curse when I see her power levels. 632 combat points!* I feed her a Razz Berry to calm her, stroke my beard, and reach for my black and yellow Ultra Balls, the strongest Poké Balls I have as a Level 23 trainer. I have only three left, and I’m all out of blue Great Balls after hours of farming Omanytes in Midtown earlier in the evening. If I can’t capture Chansey in three tries, I’m hosed. I bite my lip and toss the first ball. Swipe. She breaks out of the ball … and then runs off in a wisp of animated smoke.

I kick the curb. A nearby player offers condolences. I shake my head. She only appears two or three times a day in Manhattan, and she escaped.

The hunt must go on.

* * *

I am not a Pokémon guy. I never played the original Nintendo games and never watched the cartoon. Three weeks ago I could only name Pikachu and Jigglypuff, and that’s because they were characters in Super Smash Bros. Now I know them all. So how did something seemingly aimed at kids hook me, a grown man?

Initially I was just curious about a game my friends were talking about. When I installed Pokémon Go on my iPhone on July 12 and walked around my block in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood, I caught a few tiny brown Pidgeys and gray fuzzy Zubats—the most common Pokémon—and found the game charming but simplistic. It also seemed to freeze and crash a lot. Niantic, the game’s developer, had a lot of work to do.

I wasn’t hooked. But the next day, a friend bragged about reaching Level 12—and that got me going. I vowed to top him by hitting up a few spots I’d read about on Reddit. My brief outing ballooned into a six-hour trek. I started at the Presidio in the northwest corner of San Francisco and caught Pokémon all the way up the Embarcadero to the Bay Bridge at the eastern edge. The game’s “core loop,” or central activity, proved addictive. The more Pokémon I caught, the higher my levels rose, the more dopamine was released in my brain, and the more Pokémon I wanted to catch. Flopping into bed at 3 a.m., I was exhausted and sore but buzzing. I texted my friends to let them know I’d reached Level 18. The game had its cartoon hooks in me.

Eager to widen the gap, the next night a friend and I attended a “Lure Party” at San Francisco State University thrown by a group that calls itself Mystery Island. Lures are in-game objects that attract Pokémon when activated. Groups like Mystery Island had started finding places with lots of them, lighting them up, and spreading the word on Facebook. Unlike college parties I remembered, this one consisted of hundreds of hoodie-clad people roaming, zombielike, in a circuit around campus for hours with their noses in their phones. It was great. My friend and I both caught Kadabra, a yellow humanoid Pokémon that uses a spoon to give people headaches, and he snagged an Onix, a coal-gray snakelike Pokémon with a magnet in its brain that can burrow through the ground at 50 miles per hour.

The next evening I drove out to Beach Chalet, a restaurant known for its wide view of the Pacific Ocean but now also as the best place to catch Pokémon in the Bay Area. No one knows why, but Beach Chalet attracts a wider variety of Pokémon than any other site around, and at higher volumes. A dissonant scene greeted me when I arrived at about 10 p.m. A handful of diners finished their meals inside. A few bonfires were scattered on the beach. Meanwhile more than 100 Pokémon Go players clogged the sidewalks, front stairs, and parking lot outside. The place was overrun. Apparently that’s how it had been all week. And no wonder. In three hours, I picked up Ponyta, a majestic fire horse with hooves tougher than diamonds; Porygon, the world’s first man-made robot Pokémon able to traverse cyberspace with ease; and several other rare Pokémon, ultimately bringing me to Level 20.

Screenshot via Pokémon Go

At this point, I’d become less of a Pokémon Go player than a Pokémon Go grinder, a video game term for someone who performs low-level repetitive actions over and over again to achieve some larger result. In a classic role-playing game like Final Fantasy, grinding looks like walking your character through a forest back and forth fighting wolves and imps. But in Pokémon Go, a game that uses the real world as its map, it looks like pacing back and forth in the parking lot of a restaurant while diners and management look on disapprovingly.

You’d think game designers would want to avoid grinding. But many designers look for ways to encourage it. As an example: To unlock Pokémon Go’s Gyarados, a super-rare blue water dragon, players have to catch 100 Magikarps, common goldfish Pokémon that are terrible at everything. Since even the shorter Pokémon captures take a minute or so, unless a player can find a Gyarados in the wild (very unlikely), the only way to get one is to grind for hours—or usually much longer.

Developers encourage grinding because players either get hooked and put in the time, increasing engagement, or they start looking for ways to speed things up. This opens the door for developers to sell them in-game items for real money that accelerate progress. In Pokémon Go that means buying items like incubators that hatch Pokémon and Lucky Eggs, which double the amount of experience points you earn for 30 minutes. To date I’ve spent about $100 on Pokémon Go’s in-game items. I’m not alone. Experts estimate the game is bringing in $10 million a day from item sales. Grinding, and the avoidance of it, is big business.

* * *

But it still is a grind. Around the time I reached Level 20 I started losing interest in doing things the slow way. It was getting too hard. As you level up in Pokémon Go, you need more and more points to reach the next one. Players refer to this as the “soft cap.” Instead of needing to catch 30 Pidgeys and evolve 10 to level up, I now needed hundreds. Pitting my Pokémon against others in PokéGyms, in-game locations where Pokémon battle to earn coins and score points for your Pokémon team, had proved equally unappealing. Winning battles was just a matter of mindlessly tapping your screen. And why was I supposed to care about being on Team Mystic?

So I did what every entrepreneur does when he hits a roadblock. I pivoted, from leveling up to focusing on catching the 80 or so North American Pokémon I hadn’t snagged yet.

But how? The game had initially shipped with a radar feature that told players which Pokémon were nearby and how close they were, but a week after launch it stopped working; as of this week’s game update, it’s been stripped entirely. Without working radar to collect the rarest Pokémon, I’d have to wait at locations where they were rumored to appear and hope to get lucky. For highly evolved Pokémon like the heavily muscled martial-arts master Machamp and the 5,000 IQ psychic Alakazam, I could catch dozens of their lower forms and evolve them up—but that could take weeks of sitting in my idling car at Beach Chalet.

Fortunately, the internet intervened. While I’d been capturing Pidgeys up and down the Embarcadero, clever developers had reverse-engineered the game, building things on top of it (all in violation of the game’s terms of service) and posting them to Reddit. There were data miners, programs that log all the Pokémon that spawn in a given town or city over a period of time so Niantic’s algorithms could be analyzed and hopefully cracked. There were bots, programs that play the game on autopilot, catching Pokémon, snagging items, and racking up points. A friend launched a bot on a burner account, fed it the coordinates to the Tate Modern, and went to bed. By morning it had caught hundreds of Pokémon across London and reached Level 15.

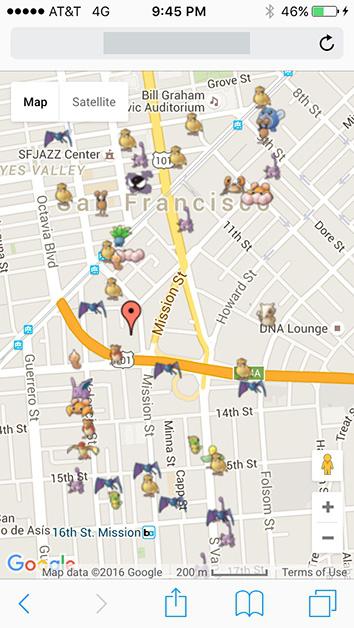

Screenshot via PokéScanner

But the most important projects were the scanners, programs, websites, and apps that map where Pokémon spawn and how long until they disappear by spoofing player presence at in-game locations and recording what appears. Some argued that using them is cheating, but with the in-game radar broken, they became the only way to see just where Pokémon were hiding.

The answers were sobering. It turns out that while Pokémon appear mostly at random at preset spawn points, the best Pokémon appear much more frequently near the tourist attractions and public spaces common in cities and large metropolitan areas. The scanners broke the illusion that rare Pokémon might appear anywhere at any time and showed rural and suburban players they were getting a raw deal.

On the bright side, the scanners opened up a whole new way to play. I installed one on a private server I SSH into from my phone. I could now actively hunt Pokémon instead of pacing around passively gathering. Thus I kicked off a new routine: Drive to a neighborhood after dark in my trusty 2001 Camry, park, and launch a scan. If it picked up anything good, I’d chart a course in Google Maps and drive to it before the time expired. I was now playing a version of Pokémon Go that looked less like Final Fantasy and more like Grand Theft Auto.

My PokéScanner was super effective. It led me all over San Francisco after dark. It led me around Bernal Heights Park, where I farmed Vulpix with its six gorgeous tails and almost mowed down a wild coyote that darted in front of my car. It led me to Coit Tower where I caught a Lickitung, owner of a 7-foot tongue that sticks to anything, and saw a second coyote jog past me. It led me to the Golden Gate Park lily pond where I caught the dopey Slowpoke in pitch darkness and ran in terror from the sound of something breathing nearby. It led me to Fort Mason to farm blue turtlelike Squirtles in the midst of a J-Pop festival. I had a blast zooming around these places at night, gassing up my car alongside the taxi drivers, scarfing down quesadillas alongside cops, even when I ended up somewhere scary.

A bit after 2 a.m. on Thursday—Day 4 of my new style of gameplay—my scanner showed Pikachu, the iconic yellow electric Pokémon, at Mission Playground with only three minutes left on the clock. I needed to catch three more to evolve one into Raichu, Pikachu’s advanced form, so I set off. I arrived in two minutes, pulled into the playground parking area, slammed my brakes and raised my phone. To my delight, there were actually two Pikachu. I caught both. As I basked in my victory, I saw movement in the corner of my eye. I looked up. A dozen men stood in my headlights surrounding my car. I looked at them. They looked at me. They looked unhappy. I gingerly backed out, then sped away. I don’t know who they were or why they were hanging out at 2 a.m. in a playground in the heart of Sureño territory, but I didn’t want to stick around to find out.

After my week hunting in San Francisco, a work opportunity brought me to New York City. I continued my steady march to a complete Pokédex, though my approach changed. While San Francisco’s sprawl promoted a car-centric lone-wolf hunting approach, in Manhattan the serious players congregate in the southeast corner of Central Park and hunt on foot, in packs. This makes for a much more social experience. In the park you’ll find players operating free phone-charging stations and others selling discounted drinks and snacks. When someone running a scanner spots a rare Pokémon, like my Chansey, they holler and like clockwork everyone picks up and swarms to that location, traffic be damned.

Brad Flora

This collaborative pack-hunter mentality works because Pokémon Go is cleverly designed to never be a zero-sum experience. If a player sees a rare Pokémon like a Blastoise and catches it, she isn’t removing it from the game so others can’t catch it. Others can all catch it too. This “plenty for everyone” design incentivizes collaboration: sharing nest locations, offering tips to boost scores, and even helping each other get from Point A to Point B.

Last Tuesday night at 2 a.m., I was at the American Museum of Natural History farming Charmander, the lizard Pokémon with a flame tail, with a group I’d just met when one picked up a Dragonite, the rare bright orange dragon, on his scanner on the far east edge of Manhattan. Three of us—me, a Wall Street trader, and a Pizza Hut delivery man—decided to split a cab and go for it. When we got there with seconds to spare and each caught our own Dragonite, it felt like a team victory.

* * *

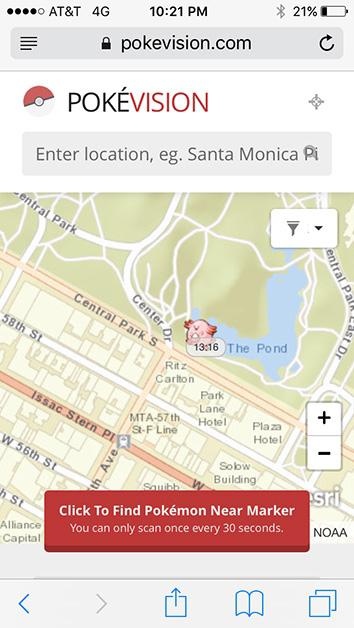

It’s 10:21 p.m. in New York, two nights after my first big miss with Chansey. I am eating a hot dog on 36th Street when PokéVision picks her up again. Hello, beautiful. She is 14 blocks north at Central Park’s southern entrance with 13 minutes on the clock. I toss the dog and hustle to the corner. No taxis anywhere. In desperation I hail a pedicab. As we travel uptown I ask the driver how much it costs. He pauses. “$5 per minute.” I feel like an idiot but can’t get too upset since we’re making good time up Sixth Avenue. We pull up to the corner and I realize I don’t have enough cash to pay and don’t have enough time to hit an ATM without losing my shot on Chansey. I tell the driver I need to run across the street for a second “to take a picture” but will be right back. He nods and I slip off to my second date with the pink dream-crusher.

Screenshot via PokéVision

There’s a crowd, players who flocked over from the park plaza en masse. I whip out my phone and spot her. Chansey. I let out a whoop when her stats appear. 244 CP. This will be easy. Not willing to risk anything, I feed her a Razz Berry again and reach for my Ultra Balls. This time I’m well-stocked. I wipe a sweaty hand on my jeans and make the first toss. A “Great” hit! The ball opens, emits light, and sucks her in. I raise my fists in triumph and look around for someone, anyone to share the moment with before turning back to the screen … which has frozen. I had run into the dreaded “Poké Ball glitch” in which the game freezes randomly after a catch.

With trembling hands I reboot the app and flip to my journal to see if I’d somehow caught her. No Chansey.

* * *

It’s been a few days now since I’ve gone out. That’s partly because of the crushing disappointment of twice missing Chansey and partly because I’ve run low on Pokémon to catch and levels to reach. Much to my girlfriend’s relief, my PokéMadness appears to be clearing. Niantic’s CEO recently stated he’s “not a fan” of the scanner apps, and the company has shut down the most popular ones, like PokéVision. (Mine is safe for now.) It makes sense. What designer likes having his or her design subverted? But roaring around San Francisco in my car at 3 a.m. and biking through an empty Times Square in the wee hours to catch a cartoon monster before he disappears was exhilarating. It let me experience the real world with the heightened awareness and focus that comes from being alone on an urgent mission. Without the scanners or working in-game radar, players will be forced back to gathering whatever Pokémon randomly spring up. It’s Niantic’s game, and I don’t want to sound too grumpy about a thing that’s brought me so many fun moments, but I, and many others, will miss being able to play it proactively.

As I come to my senses and return to a regular sleep schedule, it’s funny to think that Pokémon Go has, in fact, checked off all the boxes on my post-employment list.

I got exercise: The night I farmed Machop in Midtown on bicycle left me so tired I napped on a bench in Bryant Park before limping back to my hotel. I explored: My girlfriend has long teased me for my lack of knowledge of San Francisco, but after my night crawling I now know where (almost) everything is. (I’m not sure what to think about the fact that it took a video game to prompt this.) And I met people outside my bubble in places like Marina Green, Central Park, and Mission Playground.

But if I’m honest, I did a lot of it for the simple pleasure of going all out at something hard. Maybe, like Walter White, I did it to feel alive. Maybe I did it to fill a startup-shaped void I still have to sort out. I’m pretty sure I worked as hard at this as I did at any single thing in my company. I’ve yet to catch ’em all, and I’m not sure I ever will, but I’m close.

And I’ll be ready. Even now, my Ultra Balls are well-stocked, my spare battery is at 100 percent, and my scanner is running, searching Manhattan for the elusive pink monster who brings happiness to whomever catches her.

*Correction, Aug. 2, 2016: The article originally misstated the power level for a Chansey that the author attempted to catch. It had 632 combat points, not 1,800 combat points. (Return.)