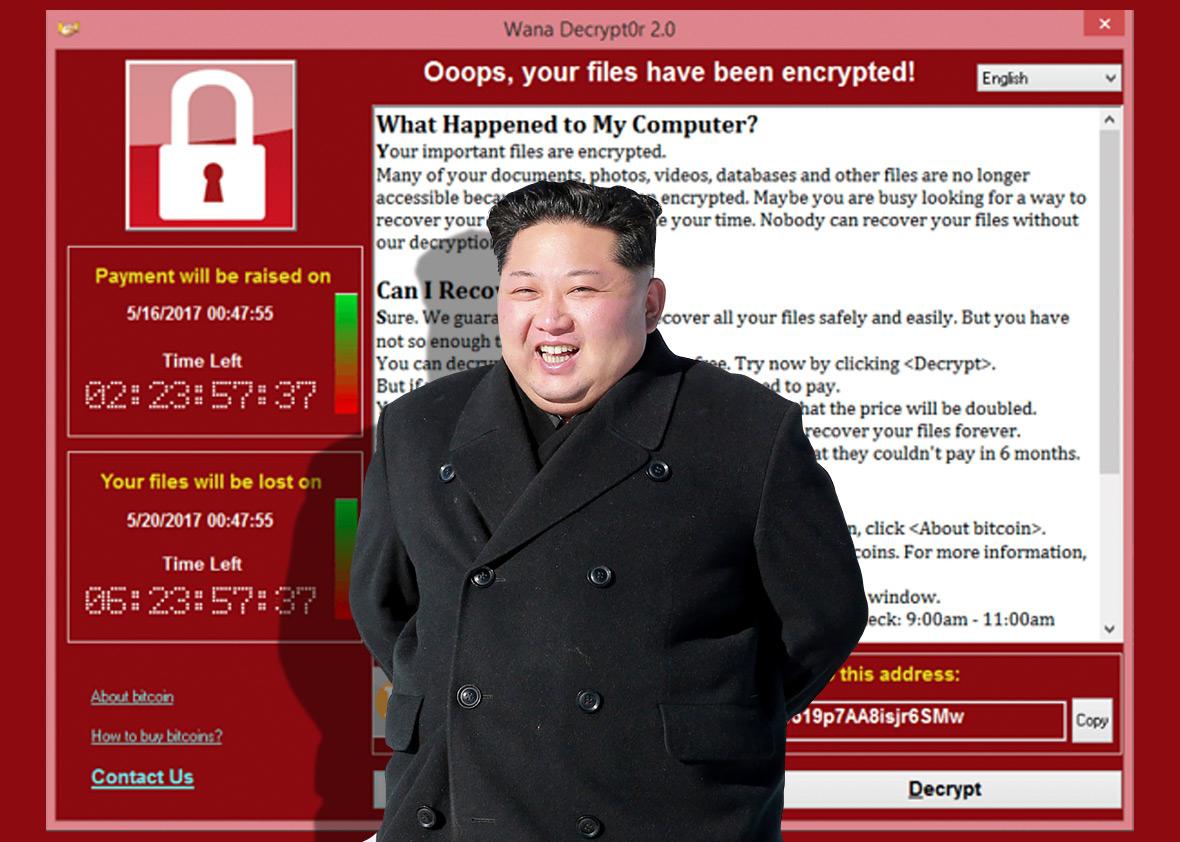

This year was bookended by two major cybersecurity accusations from the U.S. government. The first came on Jan. 6, when the Obama administration released the declassified summary of its intelligence report on “Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections,” in which it publicly accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of ordering “an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at the US presidential election” intended to “undermine public faith in the US democratic process, denigrate Secretary Clinton, and harm her electability and potential presidency.” Then, on Monday, White House homeland security adviser Tom Bossert made a similar accusation in a Wall Street Journal op-ed in which he announced that the U.S. government was ready to “publicly attribute” the WannaCry ransomware attacks to the North Korean government.

In some ways, the two public accusations from the U.S. government are very different. The first was directed at Russia and concerns an effort to influence American voters through social media, espionage, and state-run media. The second was directed at North Korea and deals with a large-scale ransomware attack that exploited a software vulnerability in Microsoft Windows to shut down hospitals, banks, and railroads all over the world. And yet, at their core, the two announcements follow a very similar template: The U.S. government directs a formal public accusation at another state for malicious online activity—but declines to provide any evidence.

The declassified Russia report tackles this problem head-on, noting on the first page that it “does not and cannot include the full supporting information, including specific intelligence and sources and methods” because releasing such information “would reveal sensitive sources or methods and imperil the ability to collect critical foreign intelligence in the future.” That’s a valid concern and a good reason to be cautious when releasing information, but it also means that readers of the report are left with nothing more to go on than the repeated assertions that various law enforcement and intelligence agencies involved in the investigation have “high confidence” in the claims laid out in the report about Russia’s involvement in the 2016 election.

Bossert’s op-ed is even bolder in its disregard for supporting the accusation it makes against North Korea. “We do not make this allegation lightly. It is based on evidence,” Bossert writes. He does not provide any of it. Instead, he points to how many others have agreed with the U.S. government’s attribution—the United Kingdom, for instance, and Microsoft. Instead of adopting the “trust us because we’re the government” tone of the Russia report, Bossert’s op-ed takes the slightly odder tack of “trust us because we’re in agreement with Microsoft and the U.K. on this.” Maybe it’s a sign of the times. At the end of 2017, perhaps many of us have more faith in Microsoft and the U.K. to tell us the truth than we do our own government.

And yet, over and over this year we have been asked to place blind faith in the U.S. government when it comes to attributing cybersecurity incidents. There is some technical, forensic evidence tying WannaCry to North Korea. But none of it comes from the U.S. government: Much of it, in fact, originates from analysis done by Kaspersky Lab, a Russian security company whose software the U.S. government banned from its own systems earlier this month due to concerns that the firm was colluding with the Russian government. And no, in case you were wondering, the U.S. government did not offer any concrete evidence that Kaspersky software posed a clear security threat. In an op-ed for the New York Times in September, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire, cited classified intelligence about Kaspersky and beyond that merely reiterated some old, tired evidence about how the company’s CEO used to work for Russian intelligence and the firm had some suspicious-looking Russian certificates on its website. Presumably the government gathers up an awful lot of evidence before it starts pointing fingers at Russia or North Korea—after all, online attribution is a tricky business, and it takes much more than just one suspicious IP address or code snippet to build a strong case for who is responsible for a cyberattack. It makes sense that the government wouldn’t want to publish every single piece of intelligence—but even a couple original forensic tidbits would be valuable.

There are several ways to interpret the government’s refusal to support its cybersecurity claims. Perhaps that reticence is due to an actual lack of concrete evidence beyond the forensics gathered by outside firms like Kaspersky. Or maybe the U.S. government has made so many public accusations this year not because it actually has its own data to back them up but instead because it wants to appear knowledgeable and confident in its ability to attribute cyberattacks to the rest of the world. I don’t think that’s the case, and I certainly hope it’s not. I’m more inclined to believe that a paralyzing fear of revealing any possible intelligence source or access method, coupled with a deeply misguided sense of the extent to which people blindly trust the assertions of the U.S. government, has led to these sharply worded but ultimately unsupported accusations.

This problem is not unique to cybersecurity. There are many areas where we are asked to take the government at its word and trust that it knows more than it’s telling us. But it’s a particularly pressing issue in cybersecurity for two reasons. The first is simply that evidence for attributing cyberattacks is rarely cut-and-dry. There are many ways to frame other people—or even other countries—for these types of attacks, and identifying a perpetrator is usually a complicated process of piecing together several different elements into a compelling narrative. So determining whether the U.S. is right about North Korea and WannaCry is not just about trusting the government to have classified satellite imagery or damning intercepted communications. It’s a question of what kinds of evidence the government has uncovered and how those pieces fit together. In other words, it’s a process that would likely benefit from some public scrutiny and broader discussion over what we consider to be sufficiently compelling evidence for cyberattack attribution.

Another reason that the U.S. government’s unwillingness to release any evidence is particularly problematic when it comes to cybersecurity issues is that Bossert’s Wall Street Journal op-ed seems to suggest the government believes that the onus for responding to North Korea now lies on private companies. He writes, “We call on the private sector to increase its accountability in the cyber realm by taking actions that deny North Korea and other bad actors the ability to launch reckless and destructive cyberattacks.” If the government’s idea of responding to nation state–sponsored ransomware attacks is to call on companies to do more, then it has a responsibility to lay out more plainly its reasons for accusing North Korea. It’s one thing for the government to act on its own secret intelligence. It’s quite another for them to demand that others act on that intelligence without being willing to reveal what it is.

If, as 2017 would seem to suggest, we are entering an era of more frequent and aggressive attribution of cybersecurity disputes, then it’s time for the U.S. government to back those up with greater transparency and clearer evidence. This is not least because the government itself seems to be at something of a loss for how to respond to these incidents.

In his op-ed, Bossert lists all the ways he believes the U.S. government has cracked down on cybersecurity this year, including banning Kaspersky products from government computers and filing a series of indictments against Iranian, Russian, and Chinese hackers. Perhaps the most telling sentence in the whole article concerns the Iranians who were indicted for hacking HBO and other American companies. “If those hackers travel, we will arrest them and bring them to justice,” Bossert writes. It’s hard to imagine that overseas hackers are reading that and quaking in their boots. (In fairness, the U.S. government did manage to arrest one person in connection with Russian cyberespionage charges this year—because he conveniently lived in Canada.) “There will almost certainly be more indictments to come,” Bossert vows in his article. But sitting around waiting for Russian or North Korean or Chinese government hackers to travel to countries willing to extradite them to the United States is not likely to be an effective strategy.

It’s not clear that the U.S. government has a lot of better options at the moment, though, which may be part of the reason it chose to make yet another very public accusation in hopes that someone else—namely, private companies—would help out. But if the government doesn’t want sole responsibility for responding to cyberattacks led by foreign states, then it shouldn’t insist on sole custody of the relevant forensic evidence, either. There are a number of difficult and important conversations still to be had about how we attribute these types of attack and interpret the evidence associated with them. Let’s hope we finally get to start having them in 2018.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.