The Federal Communications Commission has voted to repeal its net neutrality regulations, but the fight is far from over. It’s now expected that by the end of January 2018, internet service providers will have the green light to slow down access to websites that don’t pay up, block those they don’t like, and do whatever they want to manipulate how you use the internet—as long as they are upfront that they might do so. (This is the worst-case scenario, but the more likely ones aren’t so hot, either.)

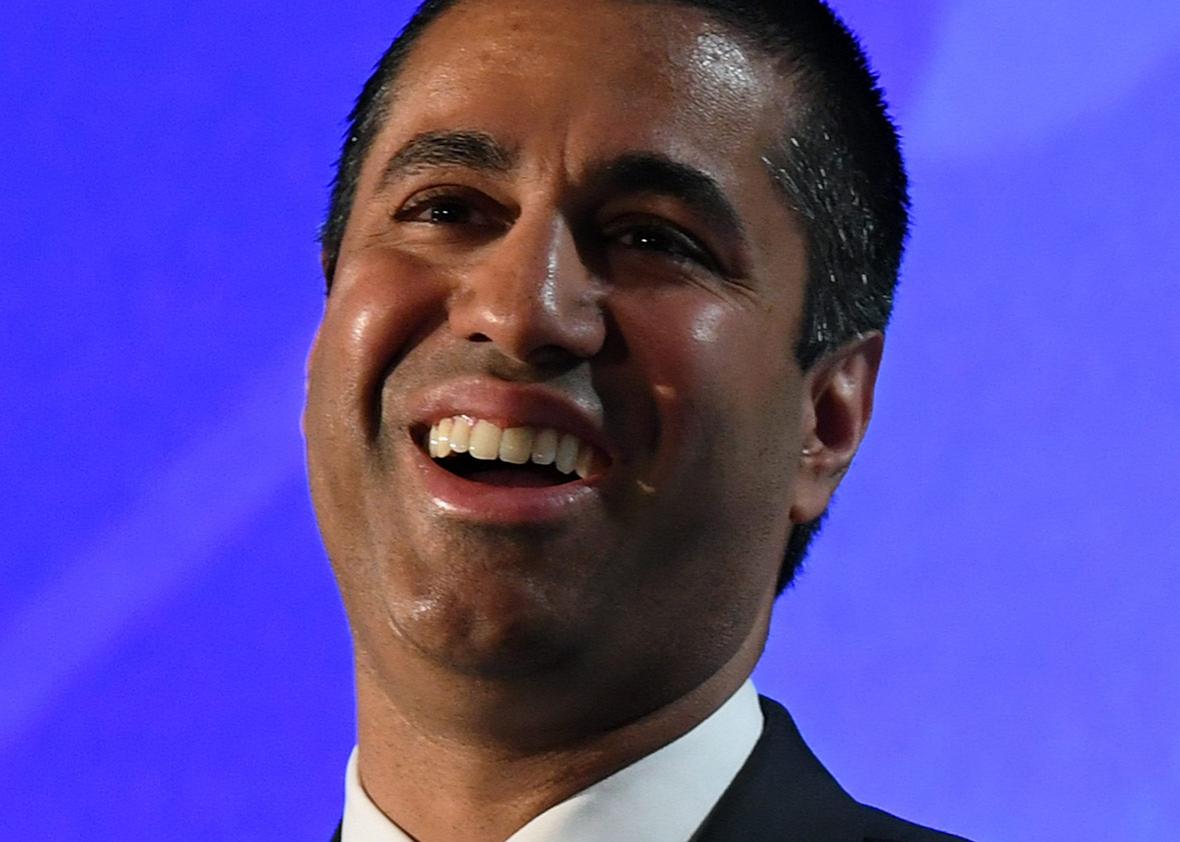

But the minute the new rules go into effect, we’ll also see the start of a battle in the courts that advocacy groups have been preparing for since Thanksgiving week, when FCC Chairman Ajit Pai dumped the news that he planned for the agency to vote to kill net neutrality by the end of the year and released the draft of the rules. “We’re definitely going to challenge the order in court,” says Gaurav Laroia, policy counsel with Free Press, a nonprofit advocacy group that opposes Pai’s plan to kill net neutrality. It will almost certainly not be the only group to challenge the new rules, as became clear after Thursday’s vote:*

In the immediate term, lawsuits probably won’t be able to stop, say, AT&T from selling faster access to HBO. There’s no guarantee the courts where lawsuits are filed will grant an injunction that would press pause on the implementation of the FCC’s new rules, so net neutrality could start to disappear immediately.

Still, Pai’s new rules aren’t on solid legal footing, and they may not stay standing as the cases start to snake through the courts. Core to Pai’s proposal is the idea that the internet should be classified as an information service as opposed to a communications service, thereby subjecting internet providers to less stringent regulatory requirements. This effectively undoes what the FCC did in 2015 with the Obama-era open internet rules, which deemed the internet a communications service—more like an essential utility—and therefore subject to certain consumer-protection requirements. Pai’s proposal argues that Congress and U.S. communications law says broadband should be classified as an information service and that he’s returning the internet to how Congress intended it to be regulated.

But that claim, according to Phillip Berenbroick, senior counsel at Public Knowledge, is in conflict with a 2005 Supreme Court interpretation that ruled it is up to the FCC to determine how the internet would be classified, which the FCC did in 2015, with the network neutrality rules Pai is trying to repeal. It also bucks a recent federal circuit court decision that reaffirmed the FCC’s authority to regulate the internet.

“The FCC is hedging its bets,” says Berenbroick, “since the argument they’re making is so in conflict with the existing body of law on this matter.” That’s why the agency also claims it has the ability to decide how to regulate internet providers, and though courts will likely give the FCC deference here, according to Berenbroick the agency will also have to “show that it isn’t acting in an arbitrary and capricious way and that there’s evidence in the record to support the analysis and defend the policy change.” The FCC has claimed that internet providers’ investment in building out broadband networks is down because of net neutrality, but that doesn’t jibe with what the providers are telling their investors. Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon have all noted on investor calls since the net neutrality rules passed in 2015 that they’ve all actually been spending more in improving and building out their networks, not less.

Another point that the FCC is likely to receive legal pushback on is the validity of the net neutrality public-comment process, which was a shady mess thanks to millions of submissions from bots, stolen identities, and Russian email addresses, as well a few dead people. The process was also targeted by a cyberattack, which is currently under federal investigation.

The FCC’s failure to address these problems before moving to vote on repealing net neutrality prevented the agency from meaningfully engaging with the comments submitted by the public, which the FCC is required to do, according to Free Press’ Laroia. Those aren’t even the only problems with that process. Under Pai’s proposal, internet providers only need to alert customers about their plan to act in non-neutral ways, like by saying they “reserve the right” to block access to websites, in order to do so lawfully. But this transparency requirement wasn’t in the original proposed set of rules that the public had a chance to review and comment on earlier in the year, says Laroia. “That’s a procedural defect in how agencies are supposed to have a process that works openly and fairly and gives a chance for people to actually comment,” on what the agency plans to do, Laroia continued.

Advocates can also argue that because the FCC’s old rules don’t actually appear to be faulty and that Pai’s push to rescind is political rather than strictly in the public interest. “If you look at the problems in the comment process, with potential fraud and corruption, and the FCC’s complete lack of interest in curing those problems, that’s not going to play well in court either,” said Berenbroick, since the FCC knew its policymaking process to repeal net neutrality wasn’t working, and the FCC did little to address it. New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman has said that Pai has refused to cooperate with his office’s monthslong investigation into the comment process.

Once the full repeal of the net neutrality rules goes into effect, the way you use the internet could start to change in ways you’ll notice and ways you might not. Some websites may load slower than others. Some services might be free while others cost more, and you may find your behavior shifting to take advantage of the new incentives laid out by internet providers. While providers try to warm their users to the idea of an internet that works more like cable TV, where you pay to access certain channels, the fight will be far from over. Thursday’s vote is probably yet another chapter in what’s sure to be a very, very long story.

*Update, Dec. 14, 2017, 2:05 p.m. EST: This article has been updated to include the news that New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman intends to challenge the FCC’s ruling.