When you’re using the internet or your cellphone or basically any electronic device that depends on wireless or internet-based connections to communicate with other machines, there’s a chance the U.S. government is collecting that data.

Thanks to whistleblowers like Edward Snowden and Mark Klein, we know that the National Security Agency and the FBI run a variety of massive surveillance programs that are designed to suck up most—even, by some estimates, all—communications that travel across major U.S. fiber-optic networks. And the U.S. surveillance dragnet doesn’t just vacuum up your digital communications. They can also track the location of your car, which is detected through the ever-expanding use of license-plate readers across the country. The FBI also has a massive database, including more than 411 million photos, made up of people swept up in various programs that contain images of faces, tattoos, and other unique identifiers.

These spying initiatives have all kinds of shady code names. There’s “Bullrun,” which is one of the NSA’s programs aimed at defeating internet encryption protocols. And then there’s “Egotisticalgiraffe,” a program to unmask users of the online anonymity network Tor, as well as “EvilOlive,” “Blazing Saddles,” and “TwistedPath,” to name a few. Not to mention PRISM, the secret spy program Snowden famously revealed that uncovered partnerships between the NSA and major American tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft.

And now, thanks to a lawsuit about a neglected Freedom of Information Act request filed today by Ryan Shapiro of the transparency group Property of the People, we know about one more federal surveillance initiative with a dodgy code name: Gravestone. But beyond the code name, we know almost nothing.

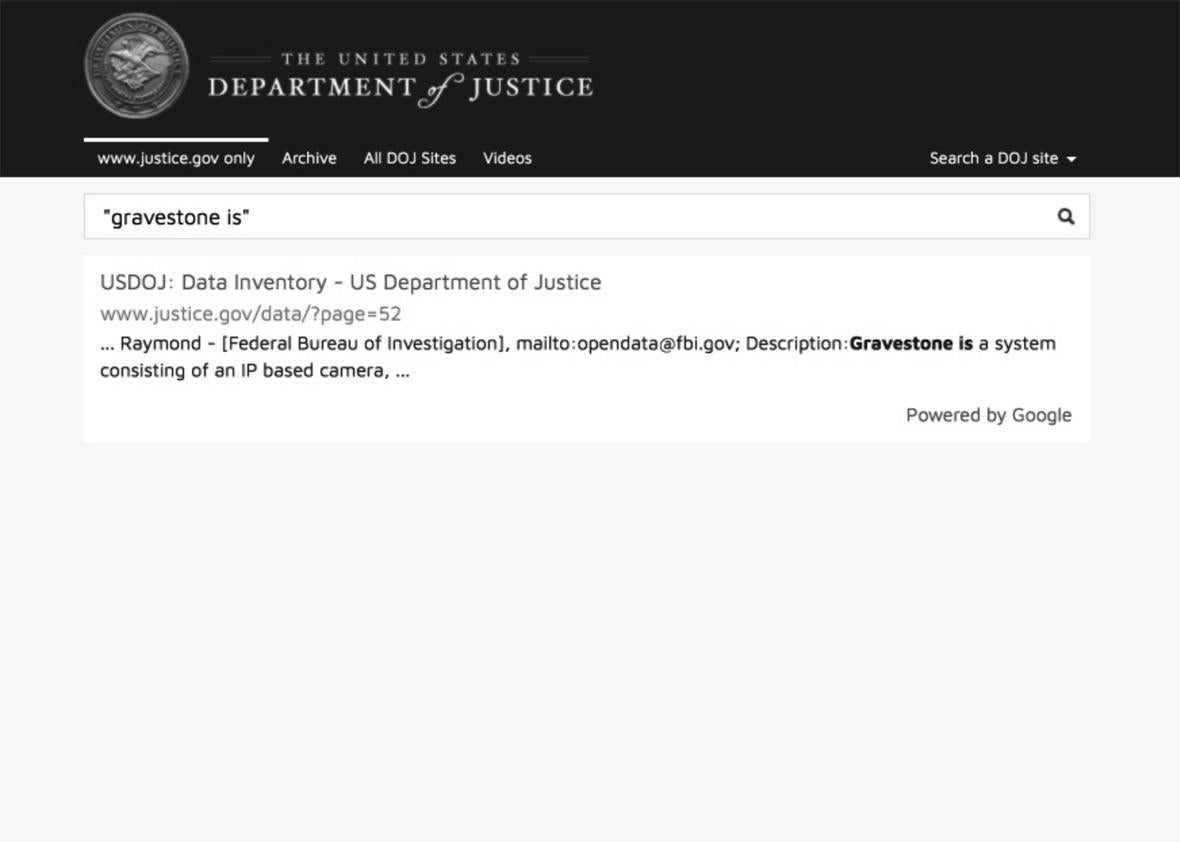

Sharpiro’s team came across Gravestone on the federal open-data website Data.gov. There, according to the lawsuit, the group found metadata about Gravestone that showed its association with the FBI. Metadata is essentially just top-line information without much detail. When President Obama’s White House said that the NSA’s phone-record collection was just “metadata,” that meant that the agency may have information about the time you called and who you called, but not the recording of the call itself. On the Data.gov website, Gravestone’s name was listed along with a very brief description of the program.

“Gravestone is a system consisting of an IP based camera, routers, firewalls, and a workstation to review surveillance video,” the Department of Justice website read. “The system provides Video Surveillance data to FBI Field Offices and is used by case agents.” An IP-based camera is the technical term for a surveillance camera that’s connected to a network. The routers and firewalls may help provide a secure way to deliver information from the cameras to whatever workstation the FBI has set up to review the footage.

Information about Gravestone is no longer available online, but Property of the People took screenshots before its removal.

But even if it’s a secret program and the description was published by mistake, it may still be covered by FOIA. “It doesn’t help to resolve any concern about a program if a two-sentence, cryptic reference to it is subsequently removed from a government website,” says Hugh Handeyside, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Security Project. “If a reference on a government website suggests the existence of a surveillance program potentially affecting the public, that certainly seems worthy of a FOIA request.”

So the only information we have to go on is the creepy code name and those two sentences. What’s actually going on here? “It’s really hard to tell given the lack of information,” says Ahmed Ghappour, a law professor who specializes in privacy and technology at Boston University. “The key here is whether or not Gravestone, or surveillance conducted using the Gravestone system, was done using a lawful warrant.” Ghappour also notes that if Gravestone is used in conjunction with a warrant and helps to make the transport of warranted surveillance video more secure, that could actually be a good thing. “If the FBI has a set of protocols for the use of IP-based cameras to conduct surveillance, then there’s obviously a legit public interest for more information.”

Shapiro and his team first filed five related FOIA requests to the FBI in March. Those requests asked for information about policy and training programs on Gravestone; any privacy assessment done by the FBI on the program; records on any security incidents, like hacking attempts; purchase and maintained records; and any additional information pertaining to Gravestone. In the development or procurement of new technologies, federal government agencies with the DOJ are required to produce a privacy impact assessment in order to understand the privacy risks and ensure proper privacy protections of any operation where personally identifiable information is obtained or disseminated. Since Gravestone is literally described as a “video surveillance” initiative that uses IP cameras, it would likely be required to have an accompanying report.

The FBI is supposed to respond to FOIA requests within 20 days of receipt, but according to the lawsuit filed Thursday, “Plaintiffs have not received a response from FBI with a final determination as to whether FBI will release the requested records.” Property of the People hopes that with the lawsuit, the FBI will be forced to respond to the FOIA request. But the team expects pushback.

“The FBI does nearly everything within its power to avoid compliance with FOIA,” says Shapiro. So he’s not surprised this had to go to court. “While FOIA with some agencies can be akin to a protracted business meeting or an attempt to get customer support from a telecom over a holiday weekend, FOIA with the FBI is a street fight.”

Still, even if the group’s entire request isn’t fulfilled, it may get some pieces, which could provide a germ to iterate new FOIA requests. And at this point, with so little known about Gravestone, basically any additional information could go a long way.

“The problem with IP cameras is that they are incredibly vulnerable,” Ghappour says, noting that the government often relies on technologies from private companies. And internet-connected cameras in particular have had serious security problems recently, like in 2016, when a botnet comprised hundreds of thousands of internet-connected devices, mostly cameras, that were then hijacked to send junk traffic to Dyn, a major domain name provider, to shut down major websites across the web including Spotify, Netflix, Twitter, and various news outlets.

In other words, beyond whether the FBI’s surveillance camera system is used with a warrant, there’s good reason to want to make extra sure that the information it collects isn’t compromised. “If the FBI has a set of standards and protocols for the use of IP-based cameras to conduct surveillance and protect them from attacks, then there is obviously a legitimate public interest for more information,” says Ghappour. If the government tries to avoid the FOIA, it may just be digging itself in deeper.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.