The internet has made it easier than ever to access information that you once had to dig through stacks and archives to find. You don’t have to have a New York Public Library card to make use of the system’s holdings as long as they’ve been digitized and made findable online.

There’s a hitch, though. Copyright-holders, including publishers and authors, can get nervous about putting material online when they still have a commercial or intellectual stake in it. Nobody wants to deny creators a living—but murky and overlong copyright terms, combined with fear and uncertainty among librarians and readers, have locked up too much material for too long without benefit to anybody. Librarians have gotten bolder, however, and with the help of copyright specialists, they have been finding more creative ways to open up material without flouting the law.

The current round of experimentation follows a decadelong legal struggle over what libraries can and can’t do with copyrighted works. In 2005, Google’s mammoth Google Books scanning project became the focus of copyright-infringement lawsuits brought by the Authors Guild and publishers. The case dragged on for years, but courts ultimately found in Google vs. Authors Guild that Google’s scanning work constituted fair use. (The Supreme Court declined to hear the authors’ appeal in 2015.) HathiTrust Digital Library fought and won a similar copyright-infringement action brought against it in 2011 by the Authors Guild and other plaintiffs.

Although Google, HathiTrust, and the concept of fair use ultimately prevailed, U.S. copyright law, as set out in the Copyright Act of 1976, remains byzantine and punitive enough that many libraries still err on the side of caution when it comes to making their holdings available in digital form. Limited bandwidth plays a role here. “Taking calculated risks is something that most large research libraries have a limited capacity to do,” says Nancy Sims, copyright program librarian at the University of Minnesota. A project like HathiTrust “is the sort of thing a library can do maybe once every 15 or 20 years.”

The latest calculated risk involving copyright comes from the Internet Archive, a nonprofit digital library based in the Bay Area. The IA does many things, including run the invaluable Wayback Machine, which archives web pages for posterity—20 years’ worth and counting now. As an independent nonprofit, IA tends to be scrappier and can afford to take more risks than its research-library counterparts.

Now it’s dared to jump over a border wall many libraries will not: the year 1923, often used to mark the boundary between works still under copyright and those released into the public domain. It’s not a hard-and-fast standard—there are both exemptions to and extensions of copyright terms—but it’s become something of a default. “We’ve had to go on the assumption that anything published after 1923 was under copyright and had to be treated with caution,” says Mike Furlough, HathiTrust’s executive director.

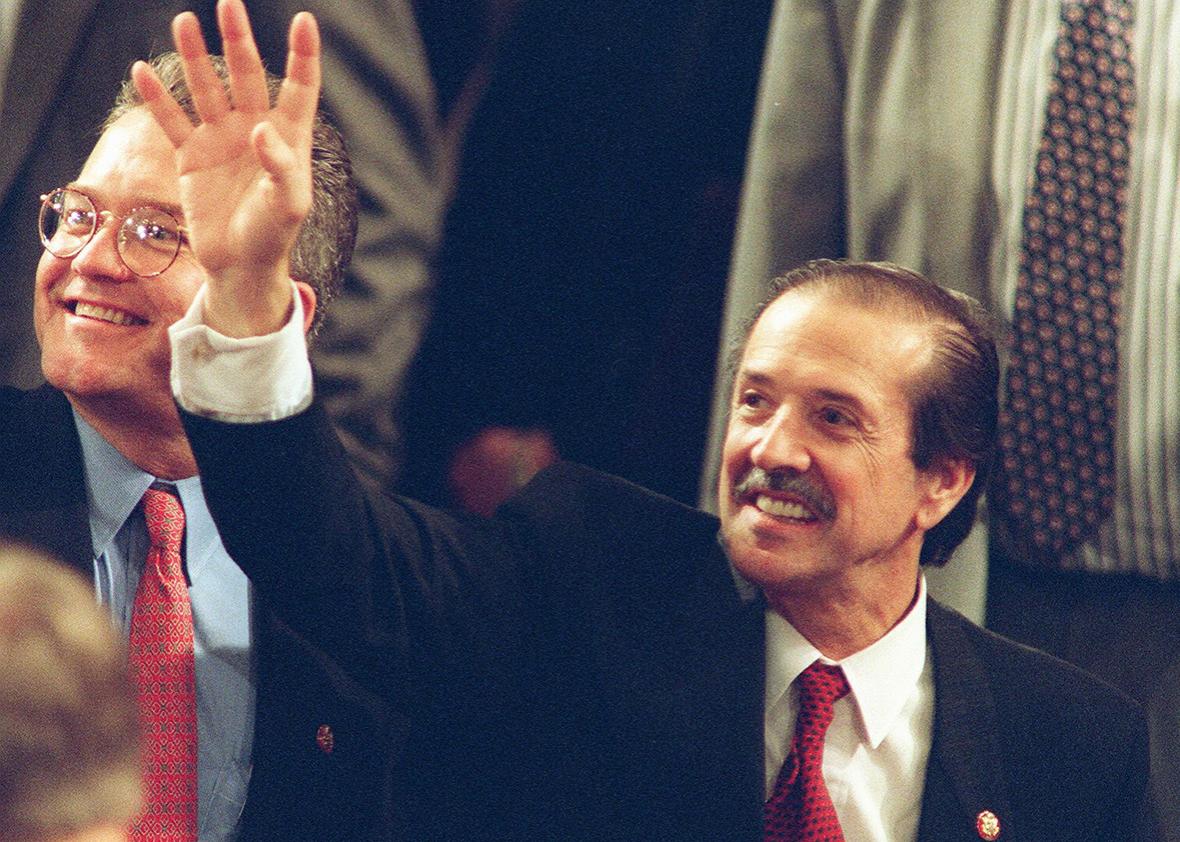

In October, the IA’s founder and digital librarian, Brewster Kahle, announced the debut of the Sonny Bono Memorial Collection. It’s named after the entertainer and California congressman who—much to the chagrin of those who felt copyright was already too restrictive—pushed to keep many 20th-century works about to enter the public domain locked up longer. Bono died not long before the passage of a 1998 law—not so fondly known as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act—that extended the copyright life of works published in 1923 or later. Big rights-holders like the Walt Disney Co. benefited. The public did not.

In a move that might tick off Cher’s late ex-husband if he knew about it, the Sonny Bono collection consists entirely of post-1923 works. It exploits an underappreciated portion of Section 108, the statute that lays out the conditions under which libraries and archives may reproduce copyrighted material. Kahle and the Internet Archive, working with Tulane University Law professor Elizabeth Townsend-Gard and some of her students, zeroed in on Section 108(h). It permits libraries and archives to make copies of works that are in the last 20 years of their copyright term—“Last Twenty” works, the IA calls them—as long as they aren’t actively being sold and as long there’s not a copy available “at a reasonable price.” In the headline of his blog post about it, Kahle crowed, “Books from 1923 to 1941 now liberated!”

A few books, anyway. So far, the Internet Archive has used this approach to add 61 books to the Sonny Bono Memorial Collection. The IA promises that many more will be added soon.

It’s not a knockout blow for copyright freedom. Users have probably not been clamoring to get their hands on some of these books—1933’s Frog, the Horse That Knew No Master by Col. S.P. Meek is not likely to be at the top of your to-read list. Still, leveraging Section 108(h) feels like a neat calculated-risk maneuver on the IA’s part. Better still, it could inspire other libraries to take more leaps into scanning mid-20th-century works, creating their own “Last Twenty” collections, and seeing if anybody cries foul. (Copyright-holders can always come forward and ask to have their works taken offline.)

The Section 108(h) approach is not a silver bullet with which to slay all copyright werewolves. For one thing, the statute leaves the definition of “reasonable” unspecified, which in this age of cheap and plentiful secondhand book–selling online could spell legal trouble down the road.

Still, people who have spent a lot of time working with Section 108 say the IA’s gambit appears to open up a reasonably safe space for the Internet Archive to operate in. “Despite the trolling name, this is a serious and significant use of § 108(h), more or less as intended,” James Grimmelmann, professor of law at Cornell Tech and Cornell Law School, told me via email when I asked him about the Sonny Bono Memorial Collection. “Their best move is also their biggest one: to systematize the process of ticking off all of § 108(h)’s prerequisites.” He points to a “companion paper” by Townsend-Gard as “the most important part of the announcement because it details what they’re doing.” The paper creates a roadmap for other libraries to follow if they want to open up more of their own “Last Twenty” material.

Figuring out whether something is in the last 20 years of its copyright is harder than it might sound, though. There’s not a central up-to-date repository against which to check whether something’s probably safe to digitize and post online. Somebody has to sort through databases and work through if/then checklists to make that call. The New York Public Library has managed “to clear a large portion of their image collections,” says Minnesota’s Nancy Sims, in part because “they had two trained lawyers working on it.”

One of those lawyers is Greg Cram, associate director of the NYPL’s copyright and information policy section. The library hired Cram seven years ago to work on research and copyright issues.

The NYPL has a repository of about 2 million digitized assets, Cram says, and it’s his job to help figure out the rights status of each of them. (An asset can be one of many things—an entire text or one scanned page of a book, a sound recording, an image.) To make that task easier, the NYPL built a system that tracks metadata: all the information the library has about each asset that can help determine whether it’s under copyright or has any licensing requirements attached. The process involves knowing when to take what Cram calls “reasonable amounts of risk” in making items available for public use. Getting sued is one risk, but so is walling off content that patrons should be able to research and enjoy.

Take the library’s World’s Fair 1939–1940 digital collection, which presents some 12,000 images from the famous exhibition—“wonderful evidence of the time,” Cram says. The NYPL holds the fair’s records as well as the photos, but Cram and his colleagues discovered that those records aren’t clear about who, if anyone, holds the copyright to the images. “At that point, we made a decision to put the collection online,” he says. It’s been six years, and no rights-holders have come forward to complain.

Is there a way to do that more efficiently and spare librarians and lawyers the chore of combing through rights metadata for every object? Maybe. Cram’s now involved in a pilot project to make the records of the U.S. Copyright Office more searchable, which would help. And there are other attempts afoot to streamline the process.

Elizabeth Townsend-Gard and her husband, for instance, have founded a company, Limited Times, that helps individuals and institutions sort out the rights status of works using a copyright tool called the Durationator. It’s a program that runs an automated series of checks on a book or other work to determine, if possible, whether a librarian or other user can share it without worrying about a visit from the copyright goon squad. Limited Times already has some institutional clients testing it out to see how much time and labor it can save them, and hopes to go wide with an institutional subscription model soon.

The Frick Art Reference Library has been beta-testing the Durationator for more than a year. For Megan de Armand, the assistant digital and metadata librarian there, says it has improved substantially over that time, and that it’s been especially helpful in answering questions about works created outside the U.S. and subject to other countries’ copyright laws. Early on, she’d get a report as long as 25 pages for each item. “Now it can be as simple as filling in a few boxes of data and getting a quick reply or loading data into a spreadsheet and getting quick items,” she says via email.

Townsend-Gard dreams of a world where librarians and researchers and students don’t have to waste time on copyright determinations. “I really believe that copyright should be more like electricity, where you don’t have to figure out how it’s made,” she says. You should just be able to hit a button and get your answer.

The Sonny Bono Memorial Collection gets us at least one small step closer to that. This winter, as you curl up by the fireside with a newly liberated digital text like Rebel in Bombazine or Father’s gone a-whaling, consider what treasures and curiosities are out there waiting for their turn to be found again.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.