India is the world’s largest democracy and is home to 13.5 percent of the world’s internet users. So the Indian Supreme Court’s August ruling that privacy is a fundamental, constitutional right for all of the country’s 1.32 billion citizens was momentous. But now, close to three months later, it’s still unclear exactly how the decision will be implemented. Will it change everything for internet users? Or will the status quo remain?

The most immediate consequence of the ruling is that tech companies such as Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Alibaba will be required to rein in their collection, utilization, and sharing of Indian user data. But the changes could go well beyond technology. If implemented properly, the decision could affect national politics, business, free speech, and society. It could encourage the country to continue to make large strides toward increased corporate and governmental transparency, stronger consumer confidence, and the establishment and growth of the Indian “individual” as opposed to the Indian collective identity. But that’s a pretty big if.

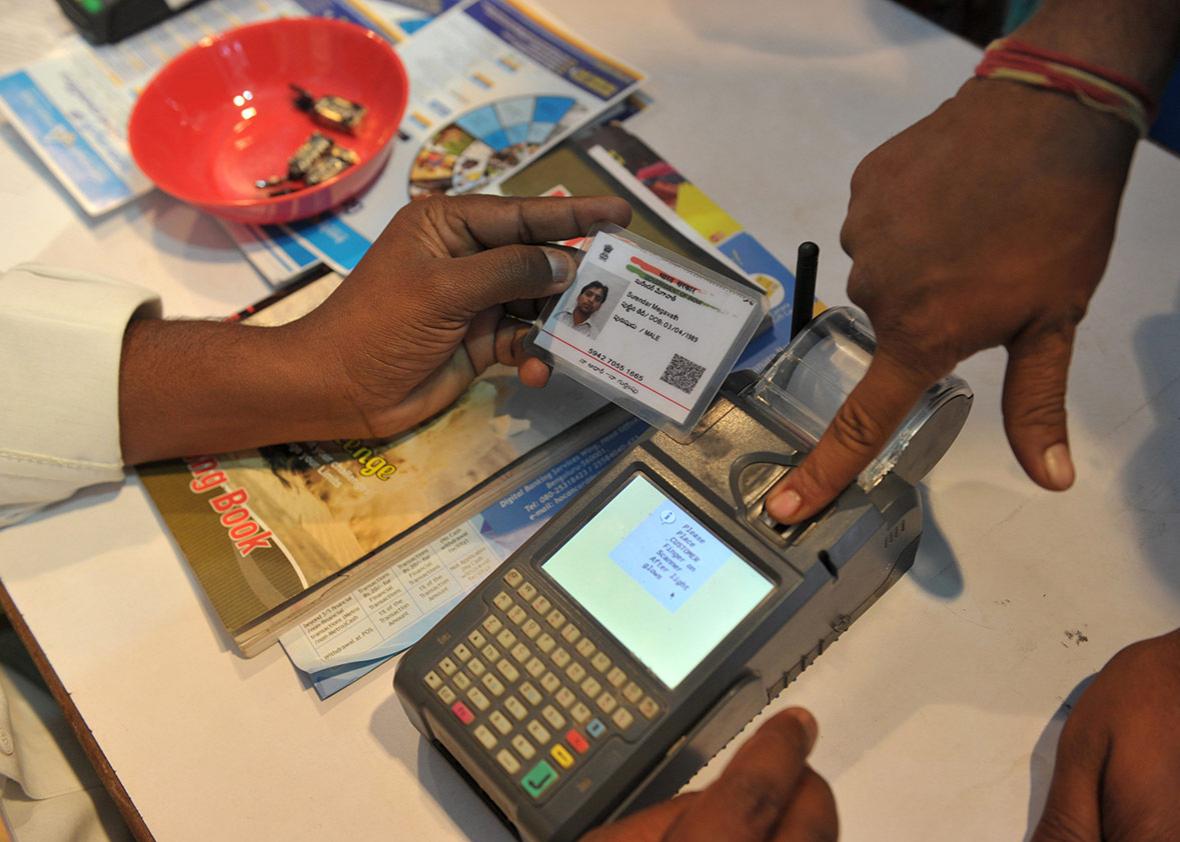

The privacy debate in India was in many ways sparked by a controversy that has shaken up the landscape of national politics for several months. It began in 2016 as a debate around a social security program that requires participating citizens to obtain biometric, or Aadhaar, cards. Each card has a unique 12-digit number and records an individual’s fingerprints and irises in order to confirm his or her identity. The program was devised to increase the ease with which citizens could receive social benefits and avoid instances of fraud. Over time, Aadhaar cards have become mandatory for integral tasks such as opening bank accounts, buying and selling property, and filing tax returns, much to the chagrin of citizens who are uncomfortable about handing over their personal data.

Before the ruling, India had weak privacy protections in place, enabling unchecked data collection on citizens by private companies and the government. Over the past year, a number of large-scale data leaks and breaches that have impacted major Indian corporations, as well as the Aadhaar program itself, have prompted users to start asking questions about the security and uses of their personal data.

However, despite the instrumental role the Aadhaar card controversy played in fueling the movement that resulted in the ruling, it’s not clear whether the ruling will actually result in reforms of the program. In a recent talk at Columbia University, Indian Finance Minister Arun Jaitley stated that the ruling would not affect the Aadhaar program, because the court established three exceptions to the new privacy protections: national security, crime detection and prevention, and the distribution of socioeconomic benefits. Given the social welfare nature of the Aadhaar program, it would fall into the third exception. However, as the program continues to expand, it seems likely that activists and other opponents of large-scale data collection will do whatever they can to make sure it isn’t exempt from the privacy ruling.

In order to bolster the ruling the government will also be introducing a set of data protection laws that are to be developed by a committee led by retired Supreme Court judge B.N. Srikrishna. The committee will study the data protection landscape, develop a draft Data Protection Bill, and identify how, and whether, the Aadhaar Act should be amended based on the privacy ruling.

The discussion on the development of the data protection rules is already becoming contentious. Kamlesh Bajaj, the founder and CEO of the Data Security Council of India, has stated that the data protection laws “should not limit data collection and use, but limit harm to citizens.” Privacy activists, on the other hand, claim that data protection laws need to be stricter and better enforced, unlike the existing data privacy rules, which in 2011 were added to the existing 2000 Information Technology Act. Despite claiming to protect sensitive personal data or information, the 2011 rules were weakly enforced.

Should the data protection laws be implemented in an enforceable manner, the ruling will significantly impact the business landscape in India. Since the election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May 2014, the government has made fostering and expanding the technology and startup sector a top priority. The startup scene has grown, giving rise to several promising e-commerce companies, but in 2014, only 12 percent of India’s internet users were online consumers. If the new data protection laws are truly impactful, companies will have to accept responsibility for collecting, utilizing, and protecting user data safely and fairly. Users would also have a stronger form of redress when their newly recognized rights are violated, which could transform how they engage with technology. This has the potential to not only increase consumer confidence but revitalize the Indian business sector, as it makes it more amenable and friendly to outside investors, users, and collaborators.

While some of the effects of the ruling remain hazy, it has already made a big difference in one way: It’s helping to disrupt Indian society through its implications on freedom of speech and expression. According to Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, homosexuality is illegal and punishable by fine and imprisonment. However, following the introduction of privacy protections in the country, several cases related to the homosexuality ban have been reopened, based on the premise that the ban is unconstitutional as a person’s sexual preferences are private, personal matters.

Similarly, existing bans on beef and alcohol consumption in states across India are also being reviewed, as people increasingly see consumption of these items as decisions individuals are privately entitled to. This demonstrates a shift toward not only reinvigorating freedom of expression and choice in the country, but also offering support for minority groups that have traditionally faced discrimination. The growing notion that individual citizens are entitled to their own private preferences and opinions also demonstrates a divergence from the family- and community-centered societies and decision-making practices that have governed India up until now.

Whether similar disruptions will emerge in other spheres of Indian society is yet to be seen. But we can be sure that any major change that occurs in the world’s largest democracy will send ripple effects through other nations.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.