Deep within a public library in Maryland, pinned to the wall of a room called the Innovation Lab, is a photograph that will cause you to look twice. It shows an adorable little boy in flip-flops, a blue T-shirt, and red shorts, nestled up against a muscular, slithering snake at least 10 times his size. The little boy, grinning, is patting the snake on the head.

The boy in the image created the photograph last year after bounding into the library with his younger sister and mother to gather images for an elementary school project. With guidance from Linda Bartkowski, a part-time librarian in the digital media resource hub, he searched the library’s free image database for a photograph of a snake, captured an image of himself in front of the green screen set up in the back of the lab, and then used photo-editing software to generate his masterpiece.

When the photo was printed, he danced around the Innovation Lab with excitement. “He was ecstatic,” Bartkowski said. “It looked so real.” But, importantly, he knew it wasn’t.

As we hit the anniversary of the jaw-dropping election of Donald Trump, the words fake news are flying around with more crackle than ever. Between erroneous accusations of fake news, the true exposés of it, and the oft-cited Stanford study that suggested that junior-high through college-age students had serious trouble judging the credibility of information online, many of us are searching for a return to something that resembles the solid ground of evidence and reason rather than swirling tornadoes of fabrication and uncertainty.

Thankfully, educators recognize that they are part of the answer and are looking for ways to teach students to be critical consumers of the barrage of media they will encounter in their generation’s highly connected world. In doing so, many are turning to media literacy training. By most definitions, media literacy involves teaching students how media content is made as well as strategies for accessing, analyzing, and evaluating the messages and bias in its content.

A recent piece in the Columbia Journalism Review, for example, explains that as of fall 2017 at least a dozen universities around the country have started offering classes that teach critical thinking in media consumption, including a University of Washington course titled Calling Bullshit in the Age of Big Data. Earlier this year, the Washington Post Magazine also profiled a series of news literacy classes in colleges and high schools. New tools like the nonprofit News Literacy Project’s Checkology, an interactive online curriculum designed to teach middle- and high-schoolers how to be shrewd consumers of news and information they encounter daily, are also gaining traction.

These reports might leave you with the impression that media literacy is a skill best saved for students in their teens and young adulthood. But the story of the little boy’s snake photo hints at what these approaches might be missing. What about media literacy education for the elementary-age set? With easy-to-use digital tools and a burgeoning recognition of the cognitive capacities of young children, we are seeing the emergence of something that didn’t exist a generation ago: new ways to teach emergent media literacy skills to children in primary grades (K–3) and, in some cases, even to preschoolers.

No, these early lessons do not, and should not, involve educators teaching first graders how to “call bullshit.” But they can expose children to new ways of thinking—an exposure that will be a precursor to the lifelong skills that the next generation will need to better understand how media is made and manipulated. Not to mention how it can be employed to deceive or evoke particular emotions.

For example, that little boy in the Abingdon Library’s Innovation Lab now has an understanding of how someone could fabricate an image. He knows how a green screen works. He has, with the guidance of a librarian, gone through the steps of selecting compelling images and considering how they might play in different forms. He’s observed digital material being manipulated with software, printed, and turned into something tactile that could be pinned to a wall (or otherwise handled, as was the case when he used the lab’s 3-D printer to create a three-dimensional model of his favorite snake).

“Libraries have always been supportive of pre-literacy skill-building,” said Mary Hastler, chief executive for the Harford County Public Library system. Those skills, Hastler said, include techniques like how to hold a book or how to read from left to right—both foundational for becoming literate. Now, she said, libraries are preparing to provide parallel digital technology skills experts think will be critical for learning to read texts in the digital age. It helps that kids love playing with tools like photo-editing software, where they can walk out with their own creation. “But it’s not just about having fun,” Hastler said. “It’s also about: How is it put together? How is it made?”

Faith Rogow, an early childhood consultant who specializes in media literacy, has been making this point for years. A founder of the National Association for Media Literacy Education, Rogow has watched children gain new skills of media understanding when they have opportunities to create media instead of just consuming it.

She also focuses on teaching the critical-thinking skills that underpin media literacy and explores age-appropriate ways to develop those skills in young children. This can mean simply doing read alouds with storybooks that include a few next-step questions. For example, in addition to asking children “What do you think will happen next?,” parents and early educators can ask children, “How do you know?,” or, “What makes you say that?”

“For the youngest children, the answers are less important than simply establishing the expectations that their answers will be based on evidence,” Rogow told me in an interview for my book Tap, Click, Read (co-written with Michael H. Levine), which focuses on teaching literacy in the digital age. “When children know they are going to be asked for explanations, they attend to media differently,” she said.

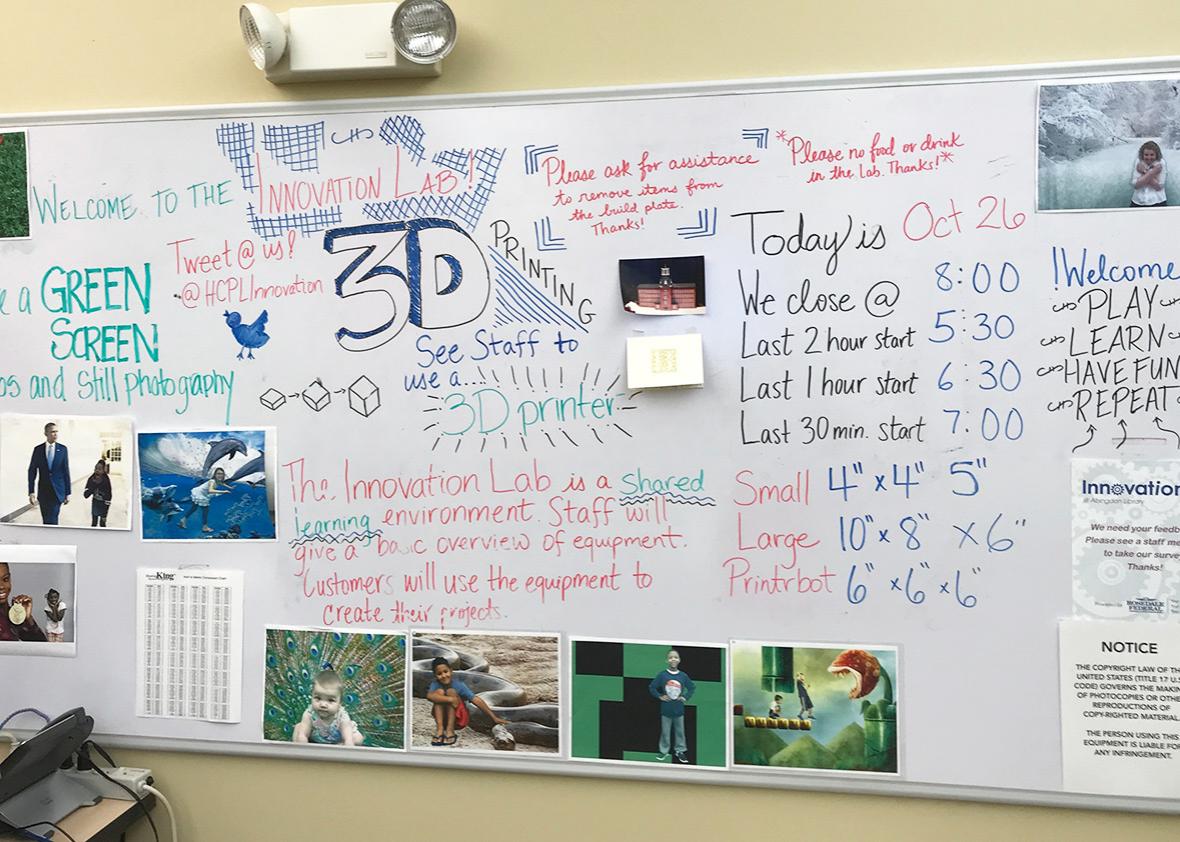

Bulletin board in the Innovation Lab of the Abingdon branch of the Harford County Public Library in Maryland.

Lisa Guernsey

Parents and educators are starting to build these media literacy skills without even quite realizing it. Last June, at a Maker Faire (a minifestival that showcases artwork and engineering) hosted by Liberty Elementary School in Baltimore, kids were already getting lessons in how media is made. Students as young as 6 crowded around teacher Christyn Wallace as she showed them how to use GarageBand software to accompany and capture the beat of their paper cups clapping on the table. Artist and after-school teacher Kathleen Mazurek guided young students as they created puppets out of popsicle sticks to use in creating stop-motion videos, asking them to think about the designs that would work best for the story they wanted to tell. Elsewhere, in pre-K centers and elementary schools around the country, educators are experimenting with e-book creation apps that can introduce their young students to the process of creating, publishing, and sharing stories.

Teachers can even use old-fashioned print books, no digital technology required, to trigger dialogue with little kids about many of the decisions that go into telling a story. For example, the new children’s book This Is Not a Normal Animal Book, by Julie Segal-Walters and Brian Biggs, takes picture books to a new level by giving readers an inside look at the battles waged by its creators. As the story progresses, the book’s illustrator (Biggs, whose words are shown in pencil) starts to rebel against the book’s author (Segal-Walters, whose words are in typescript). By Page 5, the battle gets particularly silly when the author explains she wants to show readers a blowfish, but the illustrator refuses to draw one for her and instead squirts a blob of strawberry jelly on the page. Just like the Sesame Street classic The Monster at the End of This Book, in which Grover issues increasingly dire warnings to readers that turning the pages will get them closer to said monster, This Is Not a Normal Animal Book also has a delightfully meta feel—and one that leaves young children giggling and on the edge of their seats wondering how it will end.

With such examples popping up in libraries, schools, and bookstores around the country, it feels not only possible but also imperative to start media literacy training at much younger ages.

There are many questions about what types of lessons work best and how to incorporate this curriculum with other content (say, learning how to make fake photos with snakes while also learning real facts about the creatures). It’s also important to integrate these lessons into core subjects, like learning how to read or do math, and ensure that they are sequenced so that young students’ skills can be developed with increasing complexity from one grade level to the next.

To develop a citizenry that is much savvier about media—a generation that looks critically at a Facebook post before it “likes” it and that questions the sourcing on a blog post that seems a little too sensational—we will need a much more comprehensive approach than a few creative moments in a public library.

But these early media moments provide a start. According to Bartkowski, the joy and confidence that she’s seen from the students who have used these digital tools is a sign that the Innovation Lab is already making an impression. She beams when she reflects on what a difference it made for that little boy using the green screen.

“A couple of weeks later,” she said, “he came skipping in all excited about his snake project. ‘Oh my gosh,’ he told me, ‘I got an A!’ ”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.