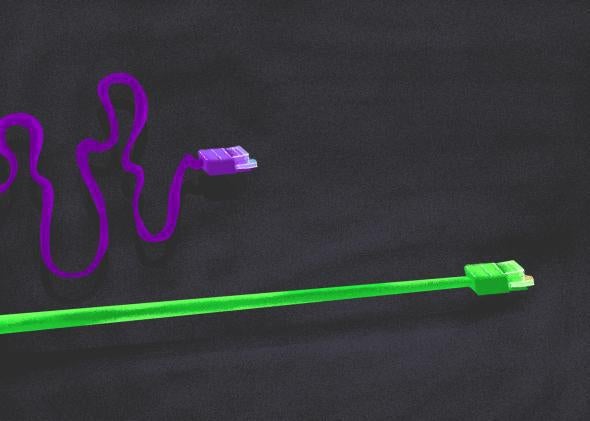

On Tuesday, Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai officially put the federal government’s net neutrality rules on the fast track for extinction. If the move goes through as expected, that means that by the end of January, internet providers like Comcast and Verizon will be allowed to charge websites to reach users at faster speeds, essentially slowing down access to websites that can’t afford those fast-lane prices—a tiered internet that the current rules preclude.

Unfortunately, the timeline for when these companies will be able to start to reshape the open internet is quite short. Pai, whom President Trump appointed earlier this year, says the FCC will vote to rescind the net neutrality rules on Dec. 14, with the majority of the commission expected to support the measure. After that vote, it will take a couple of weeks for the FCC’s policy decision to be published in the federal register, and then it will take another 30 days before it goes into effect. During those six weeks after the vote, groups that want to challenge the FCC’s decision will be able to prepare their lawsuits, sending the issue to the courts. But just because a company or an advocacy group decides to sue doesn’t mean an injunction will be granted to stop internet providers from adjusting how you’re able to use the internet.

Under Pai’s proposal, as long as internet providers disclose to consumers that they reserve the right to throttle (or slow down) access to some websites, they can basically do whatever they want to connection speeds. The new net neutrality rules only require internet providers to be transparent about their business practices. A legal challenge against a company’s deceptive practices could be made using the Federal Trade Commission’s consumer protection laws, but if companies are open about what they’re doing, it’ll probably be kosher.

And without net neutrality rules on the books, a lot of websites might not be able to afford preferential treatment. The same goes for small businesses or new startups, since the large incumbents that can afford it will likely play a role in how fast-lane service is priced. Local restaurants or hair salons that have their own websites, for example, might start to rely even more heavily on sites like Yelp to reach new customers, since their websites may load slower than those of large internet companies. When a website loads slow, people navigate away. Throttling speeds can act as an effective form of censorship—and under the fastest scenario, that could start as early as the end of January.

All of which means people who are worried about the future of the open internet have about three weeks to try to stop Pai’s net neutrality death train from barreling ahead. After the commission votes, concerned internet users then have about six weeks to pull the emergency brakes before companies like Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon are allowed to start messing with connection speeds.

There are a couple of political levers to pull that could stop the rule repeal, but all of them require public outcry, since the process is already in motion. The big one, according to Harold Feld, the senior vice president of Public Knowledge, a think tank that advocates for keeping network neutrality protections, would be to convince Republican members of Congress to simply oppose the FCC’s plan. “If you get enough Republicans hearing from their constituents that ‘We’re mad. We don’t want you to sell us out to cable companies,’ then you can imagine some Republicans potentially breaking away from the pack saying, ‘Look, why don’t you slow this down and give Congress a chance to act?’ ” Feld told me. The problem, of course, is that not many Republicans seem interested in bucking the FCC—and net neutrality isn’t an issue that robs them of sleep at night, as the repeal of Obamacare was with a handful of representatives and senators earlier this year.

But if citizens can protest loud enough—arguing, perhaps, that their new startup doesn’t have a chance of survival without a level playing field, or that their favorite local websites might see a huge drop in traffic—and enough Republicans get nervous, that opens up a few possibilities, says Feld.

These Republicans need not even come out against the FCC’s net neutrality repeal publicly. If Pai hears that there’s just too much political liability in revoking the rules, he has the political cover to slow down and not rush the vote, too—for example, because of a pending federal case in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals about whether the FTC even has the authority to regulate a company like AT&T based on how a certain FTC statute is written. Pai could say the FCC wants to wait for the outcome of that case before taking action. AT&T also filed for Supreme Court review of the original network neutrality order in September, and Pai could also choose to wait for the high court to weigh in.

Congress also has the ability to repeal an agency’s actions. There’s something called a congressional resolution of disapproval, in which Congress reverses or eliminates an agency’s action. Since Trump took office, Congress has worked to reverse more than a dozen regulatory actions—but these were Obama-era rules. While this scenario is more likely to unfold in an alternate universe where Republicans have a sensible understanding of internet policy, it’s not an unworthy goal in the one we inhabit. Republicans did, after all, resist one regulatory reversal this year, as when Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency tried to undo Obama-era climate change law in May and three GOP senators broke with their party to join Democrats in opposition and succeeded in keeping the rule in question intact. Congress certainly can undo the FCC’s decision, as remote as that possibility seems. But it definitely won’t happen unless constituents pick up the phone and call their representatives.

If you’re concerned about the fact that the internet could be a very different place in less than two months, now is a very good time to rabble-rouse. Of course, there’s no telling how fast the internet companies will move once net neutrality has been ditched—maybe they’ll proceed cautiously, perhaps for fear they will face a consumer backlash if people realize their favorite online stores and blogs are loading much slower than usual. And there’s also a chance that it won’t take long for these companies to dig their own grave, perhaps by making a site with critically important information slower to load, reminding all of us why we don’t want a tiered internet. We may not know how fast the internet will change, but it will change if net neutrality is mothballed, whether we notice it at first or not.