Indiana Jones can punch a Nazi pretty well, but we’re still better off leaving archeology to actual archeologists—especially the ones correctly focusing 21st- century technology toward making new, bizarre discoveries. On Thursday, scientists published an incredibly strange study in Nature detailing the discovery of a gigantic void inside the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, which they know is there thanks to the observation of an effect of cosmic rays formed at the edge of space that bombard our planet. It’s the first time in more than a century that a new major structure has been found in the Great Pyramid (also known as Khufu’s Pyramid), and it has eluded excavators since the pyramid was completed 4,500 years ago. Not since the Middle Ages has something this vast been found inside the megalith.

And archeologists have no idea what’s inside.

Here’s what happened: Researchers with French nonprofit Heritage Innovation Preservation Institute locked arms with a group of Japanese physicists as part of its ScanPyramids mission, which is tasked with leveraging new technologies to map out and excavate the Khufu’s and Khafre’s pyramids. To accomplish such an audacious goal, the researchers thought big. Cosmically big.

Earth is constantly hit with cosmic rays, comprising hydrogen nuclei, that break up into smaller particles when they slam into the planet’s atmosphere. Some of these smaller particles created are called muons, which zip down to the surface of the planet at near the speed of light. They survive for just millionths of seconds. Muons are everywhere all the time, and while they don’t do anything, they’re extremely tough to observe.

But if you can observe them, you can use them as a proxy for seeing things that are usually hidden. You know, like secret vast chambers sitting inside of a 4,500-year-old, 455-foot-tall pyramid. Because rock absorbs muon energy, the researchers looked for pockets of space where muons are in greater concentration.

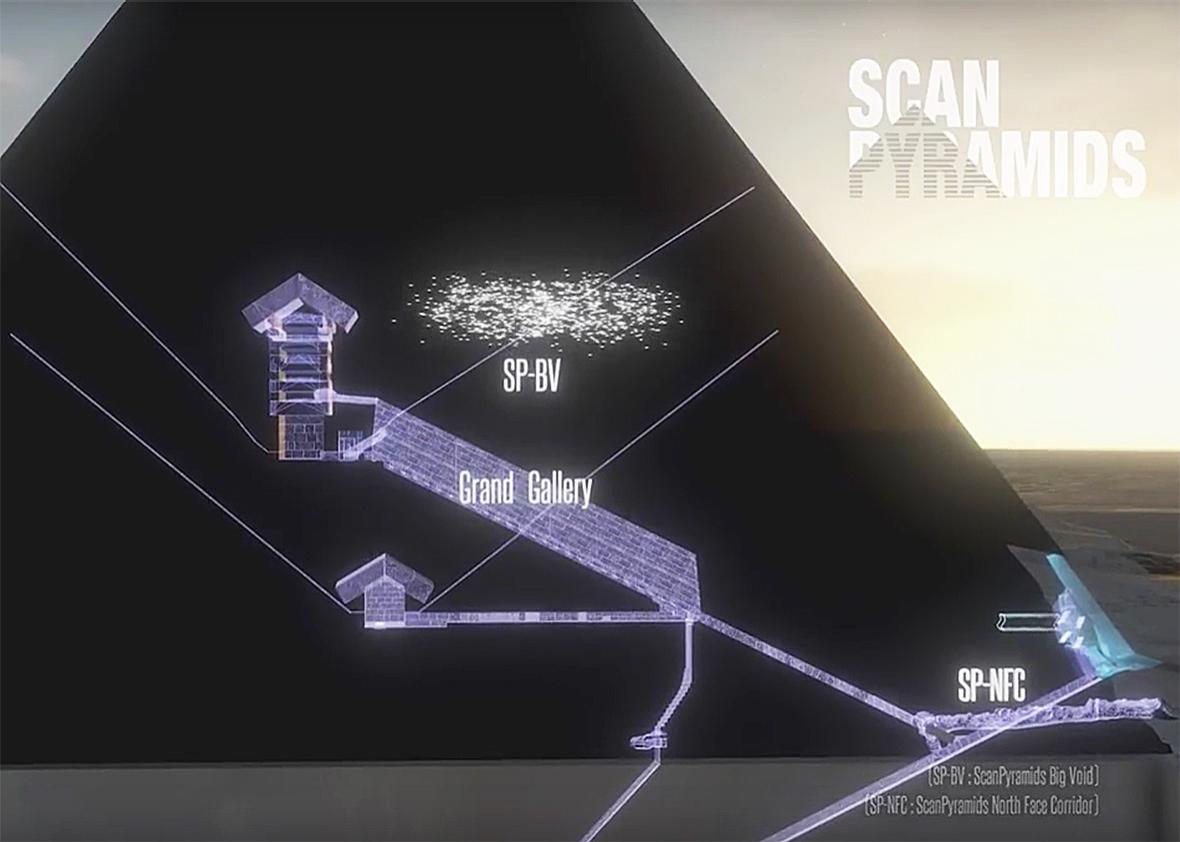

The research team managed to snag a set of muon detectors—called nuclear emulsion films—from their Japanese partners to observe muons bouncing around what they realized was a 100-foot-long cavity in the middle of the pyramid. It’s roughly the same size to the Grand Gallery, a passage that leads to the King’s Chamber. Third-party teams verifed the results of the investigation. There’s no doubt archaeologists just discovered an entirely new room sitting in the Great Pyramid.

How did such a structure stay hidden for so long? It’s not all that surprising, according to University of California, Berkeley, archeologist Carol Redmount. The void sits in the middle of the massive structure and would never have been found without advanced imaging techniques unless it collapsed into itself.

The real question, however, is what’s inside the big room? Is it a hoard of valuable, rare treasure from the era of the Fourth Dynasty? A special room for ceremonial purposes or part of the burial rituals for Khufu? The deceased pharaoh’s missing mummy itself? The discovery really just creates more questions than answers. “Being inaccessible, we still don’t know about any possible entrance points, and there may not be any, if this is some sort of construction gap,” says Harvard University–based Egyptologist Peter Der Manuelian. Moreover, he emphasizes, the muons don’t shed light about the void’s individual chambers (if any), form, size, or any possible objects.

If there are people who have a clue of what’s inside or what the purpose of the room might be, they’re not willingly diving into the speculation game. The paper’s authors don’t have much to say about what could be inside. “I know most people want to know about hidden chambers, grave goods, and the missing mummy of King Khufu,” says Manuelian. “None of that is on the table at this point. Until we know more about the shape, form, purpose, it’s not right to speculate wildly about it, at least not right for an Egyptologist.”

Redmount says that given the void’s similar size to the Grand Gallery and the knowledge that the pyramid’s interior went through several redesigns and changes before completion, the void might be another version of the Grand Gallery that was sealed off for one reason or another. Khufu’s Pyramid, she says, was built in an experimental period of pyramid development, and the Egyptians were still playing around with a lot of new ideas. It wouldn’t be a major surprise if the void were actually just a vestigial, unfinished room. That wouldn’t be the most tantalizing finding, but it would be very illuminating for experts wanting to learn more about how the pyramids and other Egyptian monuments were built.

This is the first time muon detectors have been used to score an archeological breakthrough, but it’s simply the latest in an emerging trend of archeologists making big discoveries of the ancient world using futuristic instruments. University of Alabama at Birmingham archeologist Sarah Paracak has previously illustrated the burgeoning use of satellite and air-based instruments to survey historical sites and uncover hidden details of the ancient world. “Space archeology” is now a real thing and a valuable research field in its own right.

Of course, technology will likely help scientists further explore the new room—let’s just hope we don’t have to read about a malfunctioning drone crashing into a pyramid wall a few months from now.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.