Over three days in July 1939, a group of 200-odd fans gathered in New York City for the inaugural meeting of the World Science Fiction Convention. The event’s coordinators had optimistically predicted that attendance would be five times larger, but a schism within the community had hurt turnout.

The trouble began when a small group identifying itself as New Fandom pushed out the convention’s original organizer, a 24-year-old devotee of the genre named Donald A. Wollheim. Though Wollheim and his friends, collectively known as the Futurians, still made an appearance at the event itself, some of their number began passing out radical literature to other attendees. Furious, New Fandom mastermind William Sykora banished the Futurians from the hall, forcing them to set up shop at a cafeteria across the street.

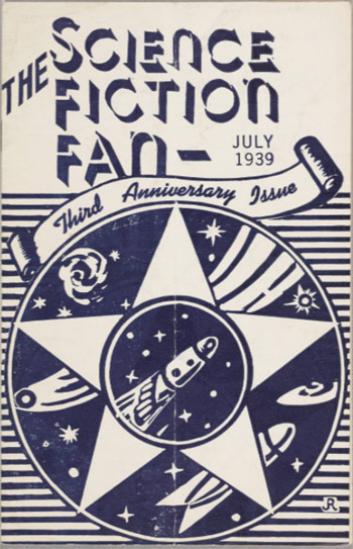

This story, which came to be called the Great Exclusion, is well-known among science fiction historians. I, however, had never heard it until I assigned myself the unglamorous task of transcribing Volume 3, Issue 12 of the amateur fanzine Science Fiction Fan, a 12-page pamphlet published just weeks after the convention that included Wollheim’s own (partisan and incomplete) account of the conflict, from which the details above largely derive. I had chosen that issue almost entirely at random, drawn in, perhaps, by the phallic rocket on its cover, but I could have easily found my way to a different text: It is just one of hundreds of zines contained within the University of Iowa’s Hevelin Collection, a massive archive of science fiction culture.

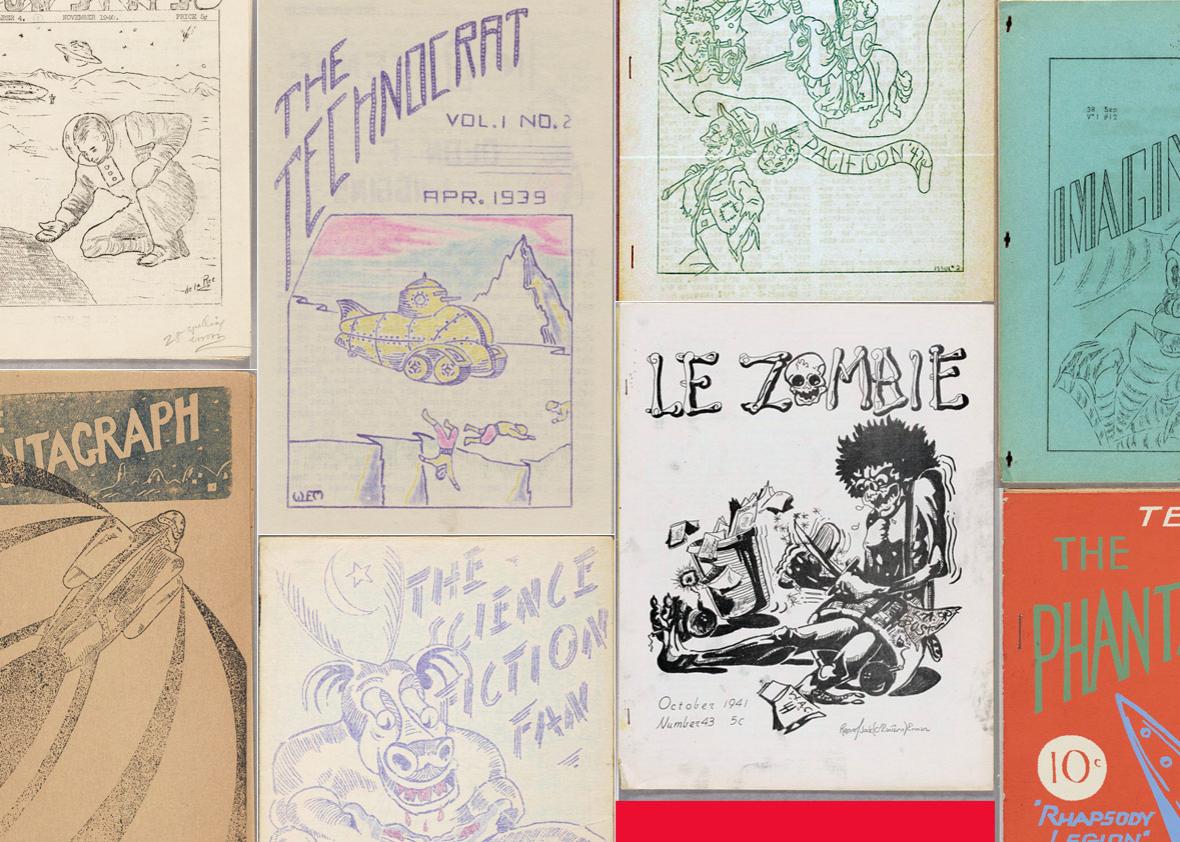

When I first wrote about the Hevelin Collection in 2015, I was attracted by the images it contained. The drawings in the zines, often colored by hand, have a crude vitality: They testify as much to the power of dreams as to real scientific possibilities. At the time, I noted that the university hoped to fold some of the publications in the collection into its larger DIY History project, a citizen scholarship effort that invites the library’s digital visitors to help transcribe objects that resist machine reading. In the past, the institution has used the platform—which sets scans of pages beside a simple text edit box—to create searchable copies of historical cookbooks, Civil War–era letters and diaries, and more.

This September, it began to include the Hevelin holdings as well. Scholars and archivists at the University of Iowa hope that the project will make the collection more accessible, both to professional historians and curious fans. “There’s really no way to know, without a lot of time spent reading through the fanzines, where this stuff is, and where the personalities exist within specific factions,” Greg Prickman, head of special collections for the University of Iowa, told me.

Those personalities were numerous, and many of them still cast long shadows over the genre. Science fiction writers Isaac Asimov and Frederik Pohl, for example, were both members of the Futurians. Wollheim, meanwhile, would go on to become an important science fiction editor who would publish early work by Ursula K. Le Guin and eventually ran his own publishing house, DAW Books. But his legacy begins in the zines: ephemeral publications with small print runs. Transferring them to a more searchable format should make it that much easier to create a fuller picture of the world he and his fellow fans occupied.

No one that I’ve spoken to understands that potential better than Pete Balestrieri, the University of Iowa’s special collections curator of science fiction and popular culture. When the library first began sorting through the Hevelin collection, it was Balestrieri who opened the boxes and examined their contents. “It was impossible for me to begin to process them, to sort them, without reading them,” he told me. That experience transformed him into a gregarious and passionate repository of anecdotes about the history of fandom, and he suggests that the collaborative transcription process might help others appreciate this complex discourse that he learned to love.

“There’s information here that’s historical. There are elements of journalism. There’s humor. There’s serious stuff. There’s both hard science and soft science,” Balestrieri said. “There’s endless speculation about the future, what we’ll see in the future, the fourth dimension.”

He also furnished the details about the World Science Fiction Convention that were missing from Wollheim’s account in Science Fiction Fan. The Futurians, he explained, had seen themselves as a progressive leftist force roughly associated with the popular front. By way of evidence, he read a passage from the document they had distributed—a text known as the Yellow Pamphlet, after the color of the paper it was printed on. It was an inflammatory screed rife with all-caps warnings to resist coercion and bullying from the supposedly right-leaning members of New Fandom.

“[Y]ou put any two fans together, and you’ve got an argument,” Balestrieri said. “You put three arguing fans together and you’ve got a convention.”

Similar debates in science fiction have continued to simmer to this day, sometimes erupting into a full boil, as they did a few years ago when a Gamergate-esque collective hijacked the prestigious Hugo Awards. In this regard, the Hevelin collection is striking in part because it helps us recognize the deeper history of contemporary struggles, plainly demonstrating that they don’t always originate in the modern internet’s toxic hobbit holes.

“There’s just this really, really clear line from the type of communication in the fanzines through to Usenet and the message boards and onto social media,” Prickman told me. “What we’re looking at is a very specific kind of human behavior and communication. The format and the tools may introduce some new factors, but ultimately it’s the same behavior.”

It may be the fragmentary insularity of historical fandom, though, that most clearly anticipates contemporary digital culture. Fan communities, whether or not you agree with their politics, can be off-putting to the outsider. Those divisions only intensify when you’re speaking with or writing for a small group of insiders—as was the case for the authors of zines like Science Fiction Fan, which had a reach of about 100 readers in 1939. Try transcribing a few pages, and you’ll likely come across peculiar abbreviations (“stf,” for example, presumably stands for “scientifiction,” a then-popular antecedent of “science fiction”) and confusing slang. These were the group’s shibboleths—a way of welcoming friends, and a warning to those intruding from without.

Hevelin Collection/James M. Rogers

Despite that, or perhaps because of it, I quickly found myself warming to the Futurians’ style. As on many of today’s fan blogs, the prose in Science Fiction Fan was frequently awkward, but even the mistakes (“suppression” is almost always written with a single p) felt like the grace notes of blooming personalities. There’s an immediacy to the zine largely absent from memoirs and reflections composed decades after the fact. This isn’t the hearty stew of retrospective history; it’s life in the pressure cooker, a banging, clanging place of raw feelings and tender egos. Studying the Futurians’ youthful writing almost 80 years later, I could feel their frustrations in the issue’s sometimes erratic spelling and see their irrepressible joy in its scattershot typography.

It wasn’t just the way they wrote that spoke to me, though; their puckish spirit also shone through in the things they wrote about. In the issue’s book review column, an anonymous critic (its byline: “Ye Olde Booke Collector”) sneers at a seemingly proto-fascist and anti-union novel by an editor at Time magazine titled General Manpower. Similarly, in the issue’s concluding essay, Wollheim savages the venerable science fiction editor John W. Campbell for “defend[ing] the monopolists of this country,” while arguing that capitalism holds back the course of scientific progress. Though they were written decades before Nick Denton was born, the catty snark and often undisguised anger evident in these pieces would not have been out of place in Gawker. Given the role that the Futurians and their fellow fans played in the rise of modern mass culture, their brio feels more prophetic than anything in the genre they loved.

In his own fascination with the Futurians and their rivals, Balestrieri inevitably turns to their youthful enthusiasm. He noted that the community grew almost silent during World War II, a conflict in which many fans served, and which not all survived. Though their voices would grow louder in the boom years that followed, as I listened to Balestrieri, I found myself thinking of a line from an early William Gibson story: “The Thirties dreamed white marble and slipstream chrome, immortal crystal and burnished bronze,” Gibson writes, “but the rockets on the covers of Gernsback pulps had fallen on London in the dead of night screaming.”

The earliest V-1 bombs were still under development while the drama of the first World Science Fiction Convention was playing out. Nevertheless, other conflicts were already unfolding in the background. “Though about a dozen British fans had promised to attend, due to what happened, none showed up,” Wollheim wrote in Science Fiction Fan, seemingly oblivious to the sterner gravity that may have bound them to home. (This was, after all, July 1939.) Nevertheless, where Wollheim and his compatriots fixated on their smaller grudges, they always knew that there were bigger stories to tell, and they believed that science fiction could help us tell them.

Many of those stories can surely be found within the Hevelin collection, waiting only for a steady hand to transcribe them. If you’d like to participate, you need to do little more than set up a free account with DIY History, select an issue from the hundreds available, and dive in. It’s hard to guess what you might find within, but the possibilities are promising. As some of us still do today, the science fiction fans of decades past imagined different worlds, sometimes better ones. Retyping their words is a welcome reminder that we have yet to write our own future.

*Correction, Oct. 17, 2017: The photo caption on this piece originally misstated that the collage contained Fantascience digests from the 1930s. It pictures a variety of fanzines from the ‘30s and ’40s.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.