Translated by Ken Liu.

On Sept. 4, a proclamation from Beijing plunged countless initial coin offering investors from heaven into hell. (An initial coin offering, or ICO, is a way for cryptocurrency ventures to raise money by selling a small portion of the new cryptocurrency to early investors.) The announcement—made by the most authoritative government agencies in banking, securities, information technology, and commerce—declared ICOs to be “a type of illegal activity” and caused the value of all cryptocurrencies to fall precipitously. The morning after the announcement, Sept. 5, the price for Bitcoin fell by 18 percent. As of Friday, as a result of regulators shutting down Bitcoin exchanges in China, the price of Bitcoin had fallen by about 29 percent, and some cryptocurrencies lost more than half of their value.

Prior to this point, there were signs that ICOs were on the way to becoming the tulip craze of 21st-century China. Many lured by the promise of unimaginable wealth and utterly ill-informed about technical details or industry trends jumped in with the hope of getting rich overnight. One particular ICO promoted by the famous investor and Bitcoin booster Li Xiaolai managed to easily raise $200 million without even publishing a white paper (similar to a traditional business plan), which is an industry standard.

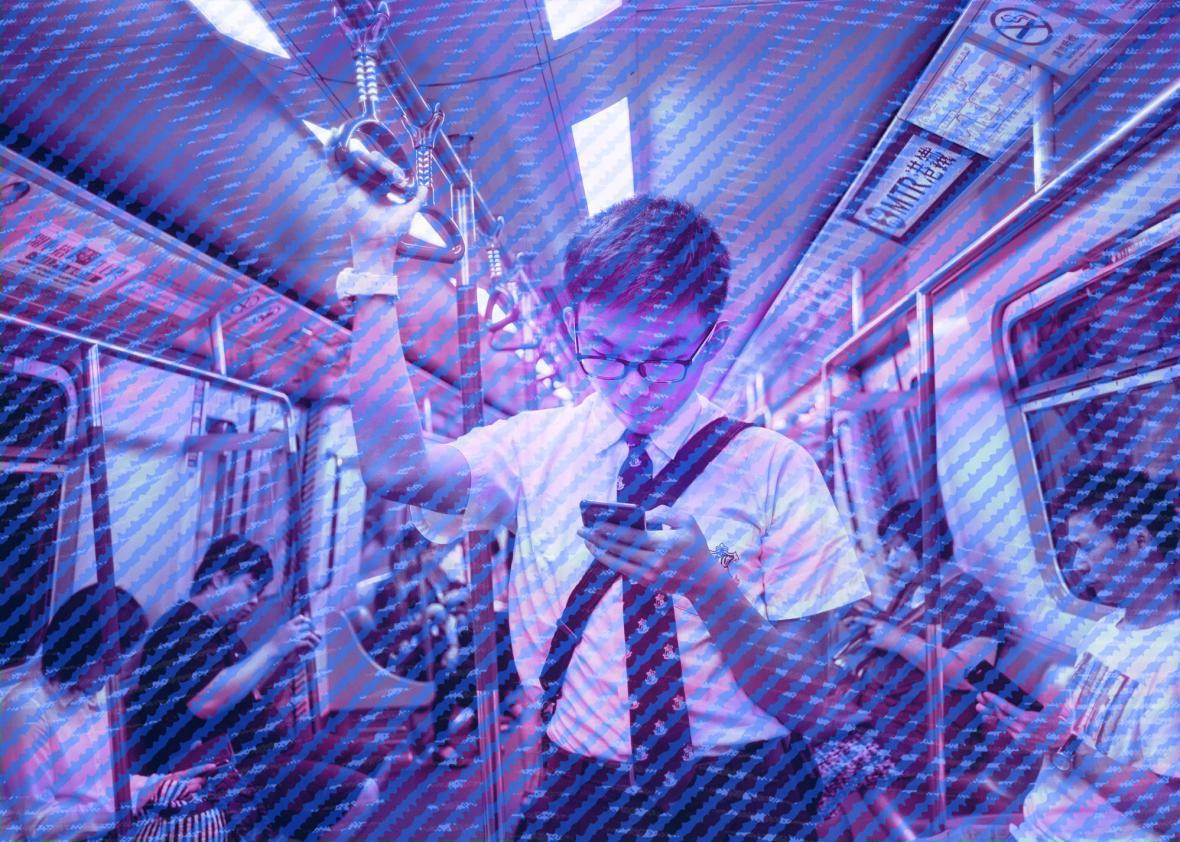

Indeed, this is but one manifestation of a mass psychological phenomenon in contemporary China that I term techneurosis. It can be seen in the fear of A.I. and robots raised at roundtable discussions, and hyped in the media and in the various tech startups that toss around “A.I.” as a key buzzword without any sign of intelligence. Those worried about being left behind by the rapid pace of technological progress can even pay for services like “knowledge insurance” (cost: about $40 per year), which grants the payer such benefits as having a “key-opinion leader’s” help with digesting a new book or understanding a new technology through a list of bullet points or an audio talk show.

The Chinese people are deeply anxious that they, or their descendants, will be abandoned by the future. As the Analects, a collection of Confucius’ sayings, observed, “anxiety comes not from poverty, but uneven distribution.” In today’s China, William Gibson’s famous quote is ubiquitous at tech conferences, on television shows, and in interviews with people from all walks of life: “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”

The Chinese have always been gripped by a yearning for absolute equality. The anti-Qin peasant uprisings in the 3rd century B.C. that held it self-evident that “kings and dukes are made, not born.” The 19th-century Taiping Rebellion promised that “there will be no distinction between high and low, and no one will be hungry or cold.” Today, we see the pursuit of a “harmonious society” and the “Chinese dream” under the People’s Republic. So China has engaged in repeated revolutions in pursuit of equality, but each time, the goal seemed to recede further out of reach. China’s 2016 per capita GDP is 155 times that of 1976’s, and yet many individual Chinese people now experience an unprecedented sense of exploitation—with a painful gulf that divides the haves and the have-nots.

The wave of technology-driven entrepreneurship during the last decade has only sharpened this pain. Tencent’s hit mobile game Honor of Kings takes in about $4.5 million each month in revenue. Its overall profits exceed those of 98 percent of all companies traded on the Chinese stock exchanges. As the media sensationalizes the myths of technology-minted billionaires and the government promotes the development goal of “everyone an entrepreneur, together we innovate,” many young people are starting companies before even graduating from college. But just as most ICO investors are interested only in the volatile daily value of their holdings or “catching a favorable wind” rather than the innovative applications of blockchain technology, many “entrepreneurs” are only chasing poorly understood trends, resulting in total loss.

Everyone is obsessed with squeezing onto the bullet train to the future, terrified of being left behind on the bottom rung of the social ladder, and clearly, this train runs on tracks built from “technological progress.” Techneurosis is simply the national lack of a unifying ideology manifesting at the level of the individual. In July, the Chinese government issued “The Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan,” and one of the goals mentioned is that by 2030, China should become a world leader in the theory, implementation techniques, and application of A.I., and turn into the world’s main source of A.I. innovation. Even the government itself seems to be techneurotic: fearful about the technology race between countries.

How can the Chinese rid themselves of techneurosis? The answer depends on a person’s generation.

The cohort born in the 1970s and 1980s, who now compose the bulk of China’s workforce, grew up hearing about the deprivations and even starvations their parents experienced during China’s recent past. The lack of career advancement and the heavy financial burden of a middle-class life—health care, elder care, children’s education, housing, etc.—only add to their anxiety. Technology cannot bring them a sense of security, but it does enable a new way to imagine how one could work and live. Emancipated from the manacles of an office job, purged of the compulsion to squirrel away wealth, they could pursue a freer, lighter way of life, one focused on the feelings of the individual rather than traditional social expectations. Thanks to web-enabled collaboration and the sharing economy, many of my friends have already taken steps in this direction.

This age belongs to those born in the 1990s or 2000s. Distanced from memories of China’s poverty and freed of worries about basic sustenance, they can truly explore and find the beat of their own lives, unconstrained by China’s traditional insistence on each person keeping to his or her place. In fact, they can break through regional and cultural biases, observing and creating as citizens of the globe. For them, technology should enable a profound organic way to experience the world, a way to realize one’s own worth through active agency, rather than merely a means of impulsive consumption driven by anxiety. From Minecraft to livestreaming, the technology-savvy young people of today’s China have built up a multidimensional world outside of physical reality, where true ideals of equality may sprout and grow.

For older generations, it will be much harder. I can only hope that they maintain an open mind toward new technologies. On matters of policy and investment, they should consult the younger generations and gather input from multiple perspectives, instead of being driven only by fear and greed.

From the May Fourth Movement that gave birth to contemporary Chinese national consciousness to the “Four Modernizations” of Deng Xiaoping, imagined visions of a technology-infused future have always propelled China’s progress. Too often, we seem to forget that China is not an abstraction of collective averages but made up of concrete, distinct individuals. Each of them sensing the future and experiencing technology in their own way, affecting those around them, and the power of such emergent disturbance can often be far more powerful than is conventionally imagined.

Only by rooting itself in the human can a technological society find a future.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.