In the history of information technologies, Gutenberg and his printing press are (understandably) treated with the kind of reverence even the most celebrated of modern tech tycoons could only imagine. So perhaps it will come as a surprise that Europe’s literacy rates remained fairly stagnant for centuries after printing presses, originally invented in about 1440, started popping up in major cities across the continent. Progress was inconsistent and unreliable, with literacy rates booming through the 16th century and then stagnating, even declining, across most of Western Europe. Great Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy all produced more printed books per capita in 1651–1700 than in 1701–1750.

Then came the early 19th century, which saw enormous changes in the manufacture of paper and improvements on the printing press. These changes both contributed to and resulted from major societal changes, such as the worldwide growth increase in formal education. There were more books than ever and more people who could read them. For some, this looked less like progress and more like a dangerous and destabilizing trend that could threaten not just literature, but the solvency of civilization itself.

The real price of books plummeted by more than 60 percent between 1460 and 1500: A book composed of 500 folio pages could sell for as much as 30 florins in 1422 in Austria—a huge amount of money at the time—but by the 1470s, a 500-folio book would fetch something in the neighborhood of 10 florins. There were even books on the market that sold for as little as 2 or 3 florins. In 1498, a Bible composed of over 2,000 folio pages sold for 6 florins. Costs continued to decline, albeit at a much slower rate, over the next three centuries. As a result, books were no longer reserved only for the clergy or for kings: Owning a printed Bible or book of hours became a coveted status symbol for the emerging class of moderately wealthy merchants and magnates.

Books remained, however, far outside the range of the common man or woman, until the price plummeted once again in the 19th century. No longer was literacy necessarily a signifier of wealth, class, and status. This abrupt change created a moral panic as members of the traditional reading classes argued over who had the right to information—and what kind of information ought to be available at all.

The shift happened thanks to major developments in both printing and paper technology. The printing press had not changed much between 1455, when Gutenberg printed his famous Bible, and 1800: The letters had to be hand-placed in a matrix, coated with a special ink that transferred more cleanly from tile to page—another of Gutenberg’s inventions—and pressed one-by-one onto the pages. The first major change to this tried-and-tested design came with Friedrich Koenig’s mechanized press in 1812, which could make 400 impressions per hour, compared to the 200 impressions per hour allegedly accomplished by printers in Frankfurt, Germany, in the second half of the 16th century. In 1844, American inventor Richard March Hoe first deployed his rotary press, which could print 8,000 pages in a single hour.

Naturally, faster prints drove up demand for paper, and soon traditional methods of paper production couldn’t keep up. The paper machine, invented in France in 1799 at the Didot family’s paper mill, could make 40 times as much paper per day as the traditional method, which involved pounding rags into pulp by hand using a mortar and pestle. By 1825, 50 percent of England’s paper supply was produced by machines. As the stock of rags for papermaking grew smaller and smaller, papermakers began experimenting with other materials such as grass, silk, asparagus, manure, stone, and even hornets’ nests. In 1800, the Marquess of Salisbury gifted to King George III a book printed on “the first useful Paper manufactured solely from Straw” to demonstrate the viability of the material as an alternative for rags, which were already in “extraordinary scarcity” in Europe. In 1831, a member of the Agricultural and Horticultural Society of India tried to convince the East India Company that Nepalese ash-based paper “ought to be generally substituted for the flimsy friable” English paper “to which we commit all our records.”

By the 1860s, there was a decent alternative: wood-pulp paper. Today, wood-pulp paper accounts for 37 percent of all paper produced in the world (with an additional 55 percent from recycled wood pulp), but when it was introduced, the prospect of a respectable publication using wood-pulp paper was practically unthinkable—hence pulp fiction, the early 19th-century literary snob’s preferred way to insult a work as simultaneously nondescript and sensational.

The problem with wood-pulp paper was its acidity and short cellulose chains, which made it liable to slow dissolution over decades. It couldn’t be used for a fine-looking book that could be passed through a family as an heirloom: It neither looked the part, nor could it survive the generations.

Traditional rag paper, on the other hand, was smooth, easy to write on, foldable, and could be preserved for centuries. Paper made from nontraditional materials, especially wood pulp, was acidic and rough. (Paper from straw, which enjoyed brief popularity in 1829 thanks to the chance invention of a Pennsylvania farmer, is durable, but brittle and yellowed. One newspaper was so unsatisfied with the quality of its straw paper that it apologized to readers.)

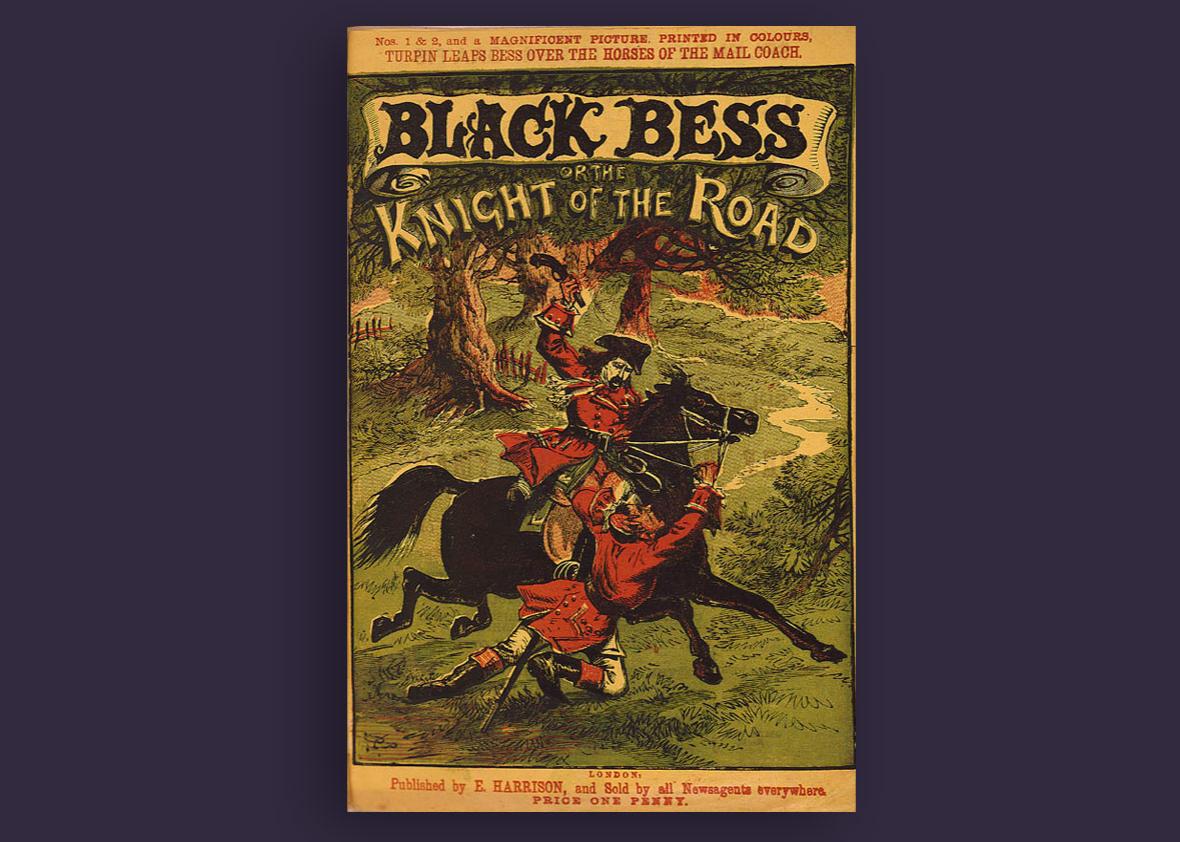

Wood pulp or straw, the cheap paper used in mass-market books sold at extremely low prices. There were a few different kinds of these books, all with descriptive (and usually pejorative) names: the penny dreadfuls (gothic-inspired tales sold for a penny each), pulp magazines (named after the wood-pulp paper of which they were composed), yellowbacks (cheap books bound using yellow strawboard, which is then covered with a paper slip in yellow glaze), and others. The cheapness that had made them so unsuitable for fine books and government records made them excellent fodder for experimental, unusual, and controversial literary developments.

Detractors delighted in linking “the volatile matter” of wood-pulp paper with the “volatile minds” of pulp readers. Londoner W. Coldwell wrote a three-part diatribe, “On Reading,” lamenting that “the noble art of printing” should be “pressed into this ignoble service.” Samuel Taylor Coleridge mourned how books, once revered as “religious oracles … degaded into culprits” as they became more widely available.

By the end of the century there was growing concern—especially among middle class parents—that these cheap, plentiful books were seducing children into a life of crime and violence. The books were even blamed for a handful of murders and suicides committed by young boys. Perpetrators of crimes whose misdoings were linked to their fondness for penny dreadfuls were often referred to in the newspapers as “victims” of the books. In the United States, “dime novels” (which usually cost a nickel) were given the same treatment. Newspapers reported that Jesse Pomeroy, a teenage serial killer who targeted other children, was “ a close reader of dime novels and yellow covered literature [yellowbacks], until,” as was argued in his trial, “his brain was turned, and his highest ambition” was to emulate the violent dime novel character “Texas Jack.” Moralizers painted the books as no better than “printed poison,” with headlines warning readers that Pomeroy’s brutality was “what came of reading dime novels.” Others hoped that by providing alternatives—penny delightfuls or “penny populars”—they could curb the demand for the sensational literature. A letter to the editor to the Worcester Talisman from the late 1820s tells young people to stop reading novels and read books of substance: “[F]ar better were it for a person to confine himself to the plain sober facts recorded in history and the lives of eminent individuals, than to wander through the flowery pages of fiction.”

These books represent the beginnings of modern mass media. At the confluence of increasing literacy rates and ever-growing urban populations looking for recreation, cheap imprints flourished. But it wasn’t just social change driving the book boom: It was technological change as well. In 1884, Simon Newton Dexter North, who would later become superintendent of the Census Bureau, wrote in his intensive study of the 10th census that the “chief cause” for the “reduction in the price” of paper “is the successful use…of wood pulp.”

For a material meant to be transient, wood-pulp paper has left its mark and the world. Forests have shrunk while literacy rates have soared, and today the hunt is on for wood pulp’s replacement. We are living in the ironic epilogue to a triumph of a hard-won Victorian-era innovation. Wood pulp paper took on a life of its own as soon as it hit the presses, and it demonstrates to a modern audience the crucial lesson that the impact of a technology goes beyond what it does: what it is made of, who uses it, who doesn’t use it, and what it represents to the people who buy it.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.