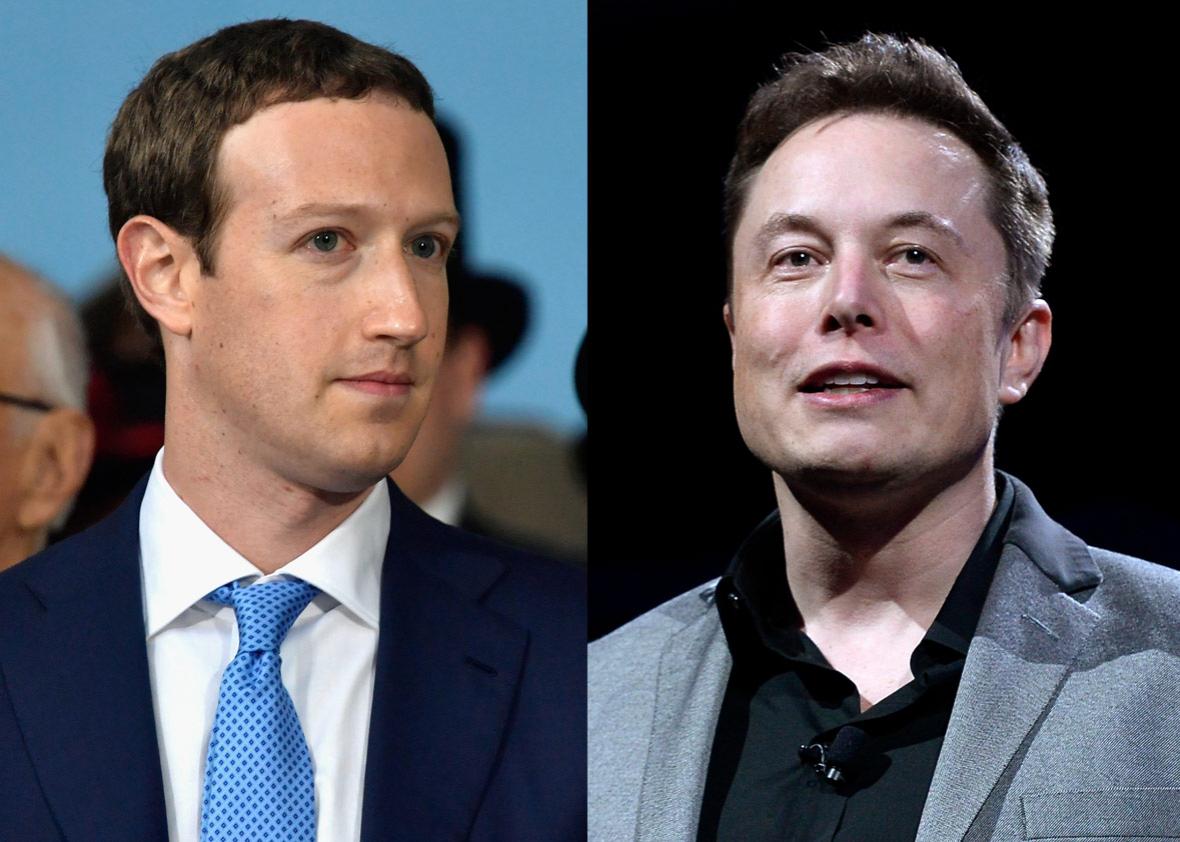

If Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk went to the same elementary school, I can practically imagine them firing “Your algorithm is so slow …” insults back and forth on the playground. Instead, as grown-up tech emperors, they barb each other on webcasts and on Twitter. Earlier this week, Zuckerberg was on Facebook Live while grilling meat and saying things like “Arkansas is great,” because he is not at all running for political office. He went on to criticize artificial intelligence “naysayers” who drum up “doomsday scenarios” as “really negative, and in some ways … pretty irresponsible.”

Elon Musk has been the foremost e-vangelist for the A.I. apocalypse. At a symposium in 2014, he called A.I. our “biggest existential threat.” He genuinely believes that A.I. will be able to recursively improve itself until it views humans as obsolete. Earlier this month, he told a gathering of U.S. governors, “I keep sounding the alarm bell, but until people see robots going down the street killing people, they don’t know how to react, because it seems so ethereal.” Musk even co-founded a billion-dollar nonprofit whose goal is to create “safe A.I.”

So many, including Musk, took Zuckerberg’s comment as a reply to Musk’s outspoken views. On Tuesday, Musk fired back, tweeting, “I’ve talked to Mark about this. His understanding of the subject is pretty limited.”

It seems like faulty logic to say someone who programmed his own home A.I. has a pretty limited understanding of A.I. But the truth is that they are both probably wrong. Zuckerberg, either truthfully or performatively, is optimistically biased about A.I. And there are plenty of reasons to question Musk’s scary beliefs.

Last week, Rodney Brooks—the founding director of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, and someone whose understanding of A.I. is unquestionably expansive—pointed out Musk’s mistake and hypocrisy in an interview with TechCrunch. He explained that there is a huge difference between a human’s skill at a task and a computer’s skill at a task, largely stemming from their underlying “competence.”

What does that mean? When people talk about human genius, John Von Neumann often pops up. His underlying “competence” was so great he made inimitable contributions in physics, math, computer science, and statistics. He was also part of the Manhattan Project and came up with the term mutually assured destruction. Brooks seems to be implying, and many agree, that computers lack that kind of fluid intelligence. A computer that can identify cancerous tumors can’t necessarily determine whether a picture contains a dog or the Brooklyn Bridge. Brooks is saying that Musk is anthropomorphizing A.I. and thus overestimating its danger.

Brooks also expressed irritation with Musk’s continued general calls to “regulate” A.I. “Tell me, what behavior do you want to change, Elon?” he asked rhetorically. “By the way, let’s talk about regulation on self-driving Teslas, because that’s a real issue.”

It’s because of this failure to regulate A.I. that Zuckerberg is right when he calls Musk’s fearmongering irresponsible, though he’s right for the wrong reasons. During the same livestream, Zuckerberg claimed, “In the next five to 10 years, A.I. is going to deliver so many improvements in the quality of our lives.” Zuckerberg was joined by his wife, Priscilla, and if “our” refers to the Zuckerbergs, he’s right. A.I. will absolutely deliver improvements in their lives. Their home A.I. will tailor their living environment to their every need, drones will deliver goods to their home, and self-driving cars will chauffeur them to meetings. However, for many, A.I. will deliver little more than unemployment checks. Reports have placed the coming unemployment due to A.I. as high as 50 percent, and while that is almost certainly alarmist, more reasonable estimates are no more comforting, reaching as high as 25 percent. It’s a different hell from the one Musk envisions.

Musk’s apocalypse is sexy. From Blade Runner to 2001: A Space Odyssey, the American public loves the story of robot uprisings and the human cadre brave enough to save us. They’ll buy tickets to watch these movies, and they’ll buy into the idea that a machine revolt could happen. The real problem, the one of human inequality, is unimaginative and depressing to think about. Neo might be able to save humanity from the Matrix, but he can’t deliver us from income inequality, unemployment, and economic displacement.

It’s in this sense that Musk’s comments are irresponsible. If we spend all our time worried that the sky is falling, we have no time left to stop and think about the very real lion’s den we’re walking into. One of the world’s leading A.I. experts, Andrew Ng, put it clearly at the 2015 GPU Tech Conference: “Rather than being distracted by evil killer robots, the challenge to labor caused by these machines is a conversation that academia and industry and government should have.”

A large part of the disagreement between the apocalyptic crowd (led by Musk) and the practical concerns crowd (like Brooks and Ng) comes down exactly to a depth of understanding. Brooks identified this in the TechCrunch interview when he pointed out that the purveyors of existential A.I. fear typically aren’t computer scientists. For A.I. and machine learning scientists, their day-to-day worry isn’t that their creations will evolve a malicious personality—it’s that they will roll into a fountain and short-circuit.

Likewise, in academia, research papers try to incrementally improve the accuracy with which computers can identify human actions in video, like eating and playing basketball. Those are concrete goals. Did the robot fall into the fountain? Did we improve our error rate? You can meet these goals or fall short, but whatever happens, the outcome is clear and concrete.

Musk and the general public, on the other hand, are consumed by the problem of true machine intelligence, a problem with no real definition. That problem is ill-defined in its bones. As famed British psychologist Richard Gregory put it in a 1998 textbook: “Innumerable tests are available for measuring intelligence, yet no one is quite certain of what intelligence is, or even just what it is that the available tests are measuring.” If we can’t define intelligence for ourselves, how should we define it for our creations?

But the well-defined technical problems of A.I. and machine learning aren’t generally interesting, and the ill-defined philosophical problems of intelligence are intractable even for experts. Instead of battling over who understands A.I. better, perhaps Zuckerberg and Musk should team up to address the A.I. issues really worth worrying about—like workers displaced by Silicon Valley’s creations.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.