At night, the skyline comes into focus slowly. In the towers, lights blink on one at a time, indistinguishable at first from the stars above. The outlines of buildings gradually cohere, some close, some farther away. Everywhere, shining pinpricks constellate.

This was “Starry Night,” one of the screen savers in a 1989 software package known as After Dark. The collection also included “Flying Toasters,” a famously kitschy animation of—yes—winged toasters flapping their way across the monitor’s flat black surface. But where those improbable aviators feel dated now, “Starry Night” remains almost timeless. One colleague tells me he remembers watching it when he was growing up in the Ohio suburbs, trying to form his own idea of what a big city might be.

I can’t recall the last time I watched a screen saver flicker to life. That’s largely because we don’t need them anymore, at least not for the reasons we once did. In the early days of computing, screen savers were a software solution to a hardware problem. Old cathode ray tube monitors were vulnerable to a condition known as burn-in, in which projecting a single image for too long would permanently alter the screen, imprinting it with a faint phantom double of the thing it had been forced to linger over. It’s this spectral quality that gave burn-in its other name, the one I’ve always preferred: ghost images.

The obvious solution was to simply turn off the monitor, and the first wave of screen savers did little more than automate that process. Leave the computer undisturbed for a few minutes, and the screen would shift to black, much as it does when a modern laptop sends itself to sleep. But as digital artist Rafaël Rozendaal explains, “Programmers later realized that you could do more interesting things. … That is when the screensaver changed from a purely functional programme into a space for play.” Along the way, they became the variegated static of early personal computing, a subtle thrum at the edge of perception.

Rozendaal, who orchestrated an exhibition at the Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam in the Netherlands called Sleep Mode that takes visitors through the screen saver’s history, suggests these programs wormed their way into our minds precisely because they allowed us to abdicate intellectual responsibility. “Most of the things we do on the computer are done with a purpose in mind, but screensavers relate to a very different part of your brain,” he says. In this regard, they represented a respite from the relatively complex, labor-intensive software of the day. Bill Stewart, one of the progenitors of After Dark, also theorizes that their relative autonomy was part of their charm. “Metaphorically, the screensaver was the equivalent of a pet dog who fed himself, was always ready to play and amuse you, but never bothered you when you were working,” he says in an interview that accompanies Sleep Mode.

Even when we chose them, personalized them, they were just there—artworks that we rarely thought of as art, partly because we never knew the names of the artists who had made them. The best examples of the genre underscored this sentiment by pushing back against the fact of conscious human design. Those flying toasters, for example, may have been totally random (in the idiom of the day), but they were also computationally random. They never fell into a regimented track, thanks in part to creator Jack Eastman’s familiarity with Monte Carlo simulations. Reflecting on the design process in a 2007 interview, he proposed, “I think that was an important idea—we had these little movies, but you couldn’t predict them.”

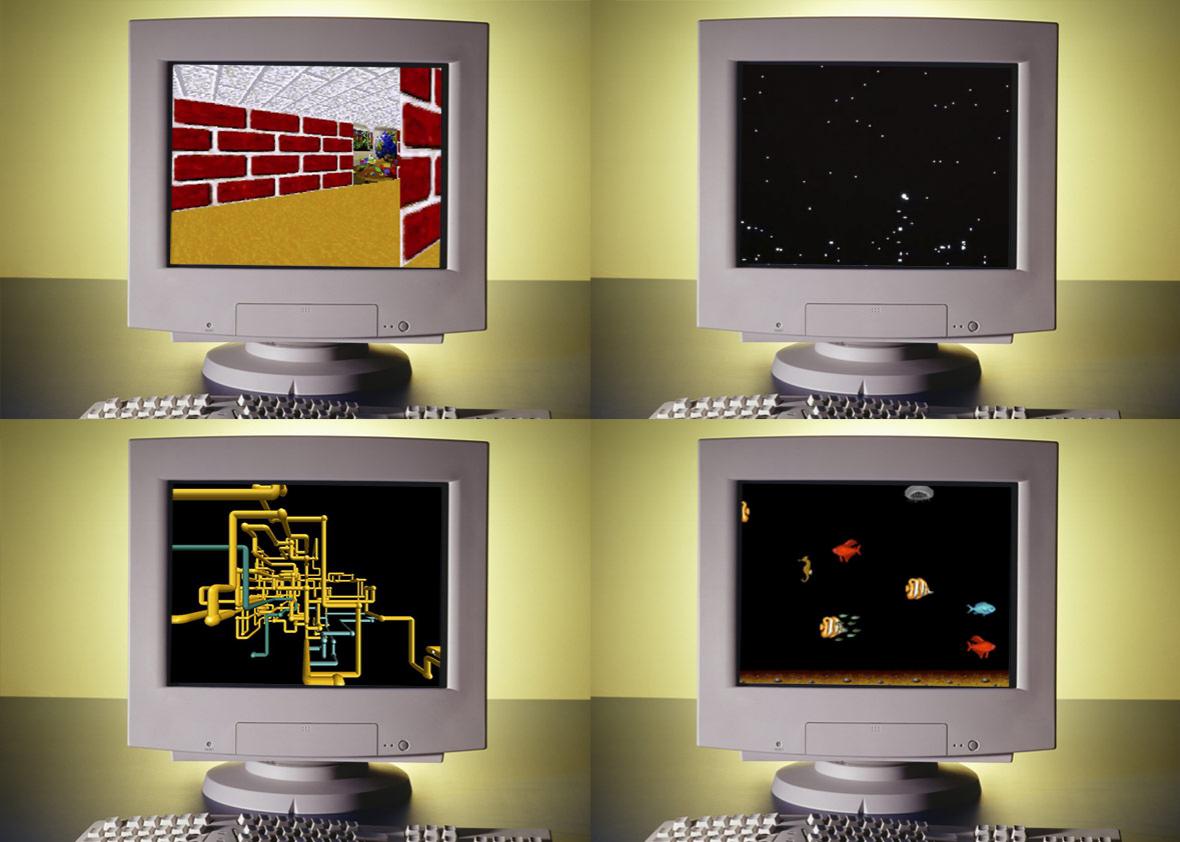

The seemingly independent vitality of screen savers told a story all its own, suggesting that our computers were always churning, working, thinking, even when they weren’t in use. Few captured this frenetic sentiment better than Windows 95’s “Maze,” a harried, first-person rush through a brick-walled labyrinth. That endless journey gave the impression of something like an intelligence at work, albeit an impoverished one. Watching it flounder was like letting your grandparents play Wolfenstein 3D while sitting by in silence as they haplessly mashed the keypad. The longer you spent with it, the more disquieted you became. Why was the maze mostly empty? Why did the invisible explorer spin so quickly? What was it running from? Why was there no exit?

Let Maze run for long enough, and you could only ever conclude that perpetual motion was the point. As Rozendaal observes, screen savers served a figurative function: They represented a kind of cognition that we could appreciate but never quite access. Look closely as pipes filled the screen, as exotic fish drifted past, as lines of pretend code shot downward, and you saw something like digital neurons firing. To watch a screen saver was to cede your own way of being in the world to that of the computer.

Perhaps screen savers lasted as long as they did precisely because we dedicated so little thought of our own to them. We could fiddle with them if we wanted to, but even if we didn’t, they were there by default. As Tyler Lacoma observes, “Because screensavers were so ubiquitous back in the 1990s and early 2000s, no one questioned their necessity.”

Maybe we should have. Unlike older CRT screens, the liquid crystal displays that have grown ubiquitous in recent years don’t really suffer from burn-in. Though they do occasionally run up against problems that look similar, those issues rarely last for long, the monitor eventually exorcising its spectral visitors. And yet, Lacoma writes, “By the time that flat-screened LCD monitors showed up in homes, the idea of a screensaver was so rooted in the consumer mind that no one ever considered ditching them.”

They’re still around if you want them, of course. Digging through my MacBook’s settings, I find 19 options buried within. But there’s a reason it took me so long to realize they’re part of OSX. By default, they wait a full 20 minutes before they appear. The system’s “energy saver” settings, by contrast, put the machine into rest mode after a mere two minutes of inactivity. There is, in other words, no circumstance in which I will ever see “Arabesque,” my newly chosen screen saver, unless I insist on its presence.

It’s possible that even these revenants will vanish soon. Admirers of Microsoft Paint mourned en masse when the company announced that it would be “deprecating” the venerable program. But far fewer observers voiced concerns that the same update would also sideline the screen saver, pushing it aside in deference to “lockscreen features and policies.” While some of the earliest screen savers had included password protection options, today security comes first, far more important than the whimsical creations that once danced across our monitors.

If the screen saver lives on, though, it likely won’t be in the interest of preserving such playful visions but because idle screens represent increasingly valuable swaths of real estate. Think of your dormant Kindle recommending the latest Jodi Picoult novel or Netflix autoplaying promotions for its original programming. These companies have learned to exploit the very thing Rozendaal admires in older screen savers—the way they snuck into our heads while we were idle. The weird noise of computing’s past has somehow gathered into commercial signal.

Maybe the change was inevitable. Screen savers were always disappearing; that was the point. Move your mouse, hit a key, and they vanish. Though their animations were often hallucinatory, it was that insubstantial quality that made them truly phantasmagoric. They operated at the outer limits of attention, engagement, and interaction. Screen savers belonged to a world we could only ever observe, a world of dreaming machines.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.