Back in early 2014, thanks to a confluence of digital malfeasance and wide-eyed optimism, bitcoin enjoyed a nice run in the headlines. Things have since quieted in the popular press, but venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, and speculators have continued to work toward the promise of a secure, fast, and cheap payment system that cuts out fee-hungry banks and credit card companies. Following Bitcoin’s lead, they’ve built dozens of competing cryptocurrency systems, and while digital coins aren’t part of most people’s everyday lives today, it’s increasingly clear that they will be, sooner or later.

Bitcoin itself, however, won’t necessarily be part of the future it has ushered in. A broad surge in cryptocurrency values pushed the original recipe north of $40 billion in late May, but a long-standing issue that limits the system’s capacity has left it struggling to give users what it says on the tin: a cheap, quick way to move money. Because bitcoin is open-source and democratically managed, a huge number of stakeholders are wrangling over how to solve this scaling crisis, which hinges on an obscure technical parameter.

In response, the bitcoin community has split into two factions that tout mutually incompatible solutions while accusing each other of incompetence, conspiracy, self-aggrandizement, and generally being the devil. On March 17, more than two-dozen bitcoin marketplaces issued a joint letter warning that there is a “very real possibility that a Bitcoin network split may occur in the future” if the conflict isn’t resolved. It was one of the first high-level acknowledgments that, just as it begins to fulfill its promise, Bitcoin could be torn in half.

The idea of a Bitcoin split, or the extremely personal infighting that has made it a possibility, would have seemed laughable just a few years ago. Then, a tight-knit crew of bitcoin pioneers gleefully nerded out over an arcane innovation with world-changing potential. At the heart of bitcoin’s radical promise is the so-called blockchain, essentially a ledger where transactions are recorded. But instead of some spreadsheet living on a single computer, the blockchain exists on thousands of servers worldwide that constantly monitor one another’s copies of the ledger. This makes the network essentially unhackable—an astonishing achievement of computer science and economic engineering.

Since a still-anonymous creator introduced bitcoin in 2009, its central innovation has given birth to a diverse and thriving ecosystem. There are now dozens of other cryptocurrency systems, with names like Ethereum, Dash, and Ripple, many with more features than Bitcoin. Perceived instability in Bitcoin could eventually push investors and developers to these alternatives. But more profoundly, Bitcoin’s inability to solve its own problems would cast doubt on its core libertarian-democratic premise: that people don’t need the government or banks to manage their currency.

If Bitcoin were to split, it will be because it was just too successful for its own good. Public interest and transaction volume has grown more or less steadily for the past five years, and the “blocks” that make up the blockchain—bundles of about 2,000 transactions compiled every few minutes—are getting very crowded. Some transfers can currently wait hours, even days, to go through.

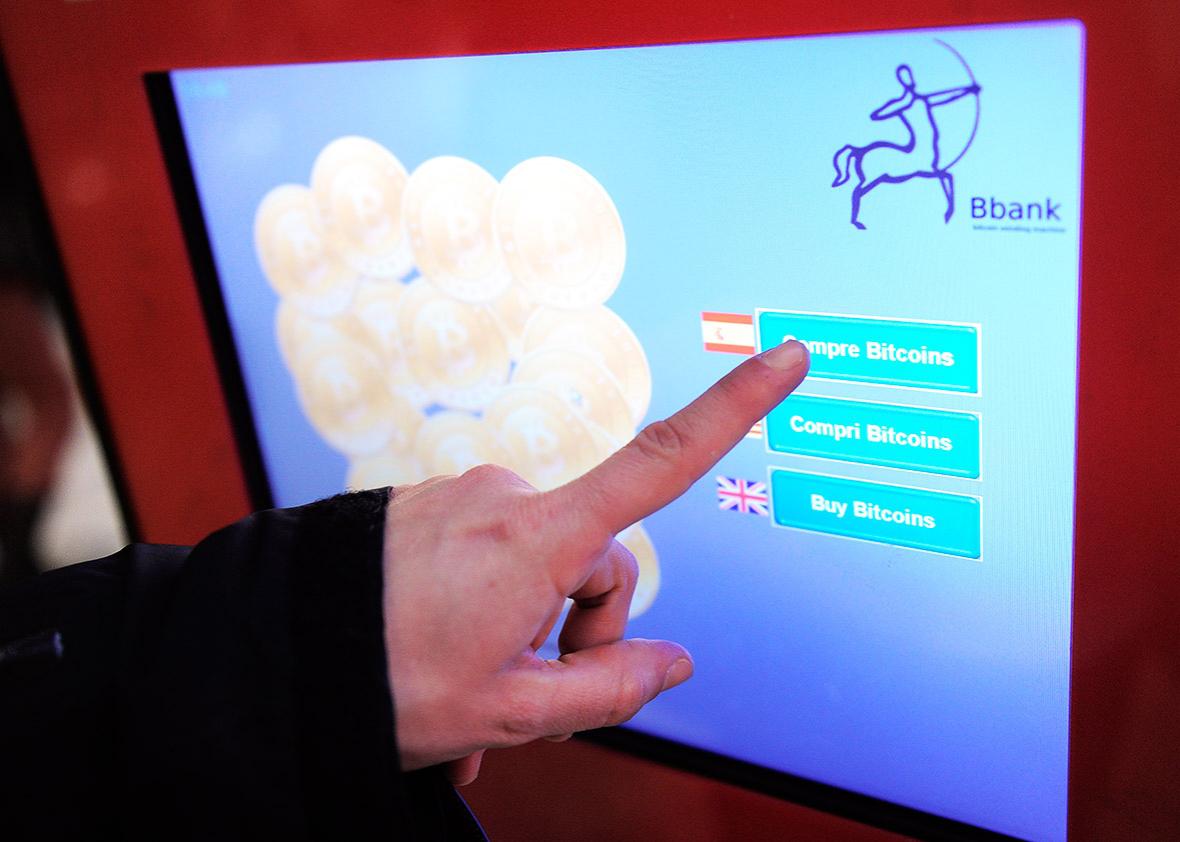

Users can pay a fee to have their money moved first, through a bidding process that is becoming increasingly fierce. Before 2014, bitcoin transactions were effectively free. By October, users had to pay operators about 13 cents to get speedy resolution. Today, that average fee is closer to 50 cents. That removes some of bitcoin’s appeal as an alternative to, say, Visa, which charges merchants about 10 cents for small transactions or about $1 for the average swipe.

Almost everyone admits this is a problem, but bitcoiners are divided into two camps over how to solve it. One faction is led by Roger Ver, a very early funder of Bitcoin startups who has relentlessly proselytized for the technology since 2011. Among the cultish ranks of bitcoin boosters, Ver’s commitment and vision earned him the nickname “Bitcoin Jesus.” Now, he has taken up the banner of Bitcoin Unlimited, a solution to the scaling issue that would directly increase the code’s limit on how much data a block can hold.

While this would make bitcoin faster and cheaper for users, critics say it would also make it more expensive to run a server. For this heresy, Ver’s enemies have rechristened him “the Bitcoin Antichrist.” One of his main allies, the Chinese server manufacturer Jihan Wu, has been similarly dubbed “Jihad Wu,” complete with a satirical Twitter account that paints him as an ISIS-style terrorist.

The main competing proposal is offered by Bitcoin’s central development team, Bitcoin Core, and is known as Segregated Witness, or SegWit. It would free up a smaller amount of space for transactions, while making it easier for secondary systems to handle smaller transactions outside of the main, super-secure blockchain. But it could leave bitcoin proper nearly useless for small transactions.

This may sound like a technical squabble among quislings. But the two solutions imply two fundamentally different visions of what bitcoin—a system that currently has a higher market value than Credit Suisse—should be. Those who support Ver’s vision of larger blocks want bitcoin to be a day-to-day, “open” payments network, usable to buy anything from a cup of coffee to a car. Those who support SegWit are more likely to see bitcoin as “digital gold,” a long-term store of value that wouldn’t move around that much. That would leave fees high but make paying them less necessary, while relying more on secondary systems.

The two factions congregate on separate, opposing Reddit forums where they each tout their solution while meme-trolling the enemy. Each accuses the other of sockpuppeting—using fake social media accounts to create the impression of popular support. (And each side, of course, denies in engaging in such behavior.)

If Bitcoin were a company, you’d expect the CEO to sort out his or her underlings’ petty backbiting. But Bitcoin has no leaders. Instead, the “miners” that run Bitcoin’s servers essentially vote on any proposed changes. For years, the consensus version of the software was distributed by the slowly rotating Bitcoin Core team and adopted with little controversy. Core had no official authority, but its expertise was broadly trusted.

But many miners have lost faith in Core, accusing it of moving too slowly to tackle the scaling issue. According to tracking site Blockchain.Info, a little more than 40 percent of miners are currently signaling their support for Bitcoin Unlimited, compared with only 30 percent signaling for SegWit. If more than 50 percent of miners were to support Bitcoin Unlimited, they could force a shift in the entire network. Ver, though, says he would like to see much more decisive margins of support before any changes are implemented, and SegWit requires support from 95 percent of miners before it can be activated.

With each faction so firmly entrenched, there’s no sign things will sharply swing either way any time soon. But a smaller group of miners could branch off to form a separate network and an entirely new currency. This split, known as a “hard fork,” is what the exchanges that issued the March letter were planning for.

Not everyone thinks a hard fork would be a bad thing. Anthony Di Iorio was one of the founders of Ethereum, the most prominent system to innovate on bitcoin’s core ideas. “Should there be a hard fork,” he predicts, “you’re going to have better growth. [Users] will be able to decide. Competition is good.” Ver, unsurprisingly, describes a fork as “not a big problem at all.”

But others—naturally—disagree. Reggie Middleton is a financial analyst focused on cryptocurrency and runs the decentralized trading platform Veritaseum. “A Bitcoin Unlimited fork would be destructive to the economic value of the [Bitcoin] network as a whole,” he says, in part because the strength of any payments system hinges on its size.

Middleton is also concerned about Bitcoin Unlimited’s implications for bitcoin’s governance. Like Ver and most longtime bitcoin supporters, he’s a staunch critic of government and corporate power, attracted to bitcoin because it promises to free currency from control by old regimes. But Bitcoin Unlimited’s larger blocks would require more computing power, storage, and network bandwidth to process, which could concentrate mining in fewer hands, making the system both less secure and less democratic.

“Once you centralize it,” says Middleton, “you open it to threats. It would become like the banking system, which is basically greedy middlemen who stand between you and your money.” For bitcoin die-hards, there is no greater slur than comparing something to a bank.

Ver thinks this position is ridiculous. Bitcoin was once a true grassroots project, with ramshackle servers toddling along in people’s basements and dorm rooms. But the system has already become vastly more power-hungry: Ver points out that a single usable mining server, and its voting power, today costs $1,000 or more. In other words, bitcoin is still a radical political project, but it’s also big business, and it’s time to come to terms with that.

Jeff Garzik has a unique perspective on the public bloodletting. Before spending four years as part of the Bitcoin Core team, Garzik was a leader at Red Hat, which helped make the open-source Linux system digestible for corporate users. Someone had to play that insulating role, because it was common for Linux’s democratic community of developers to engage in ideological warfare over lines of code.

But Garzik says that even Linux’s biggest battles can’t compare to the hate swirling around bitcoin’s block-size debate. While Linux fights might have broken out over engineering approaches, and early bitcoin debates revolved around ideology and theory, Garzik thinks something much less abstract is driving bitcoin’s current unrest: money.

At this point, more than $1.5 billion in venture capital has gone to support blockchain startups, and many have business models that would be affected by how the block-size problem is solved. Blockstream, which employs some Bitcoin Core developers, builds “sidechains,” the sort of secondary system that would be more in demand if bitcoin itself doesn’t start accepting more transactions. On the other hand, there’s BitPay, which has sold merchants the idea of bitcoin as a low-fee retail payment system, and for whom the strangled state of the bitcoin blockchain has been a serious headache.

“You’re asking developers, in effect, to pick winners and losers in the market,” says Garzik.“There’s no right answer.”

But there could be a wrong answer. A miscalculated change could disrupt bitcoin’s basic economics, a fine balance of computing costs, coin value, and network demand. And all of those competing blockchains are waiting for a mistake. If bitcoin were to recede, “that will be sad for me,” says Ver. “If there’s another iPhone that’s better, that’s sad for my old iPhone. But it means we get to use a better one.” Ver has outlined this endgame scenario on the same portal that he established years ago as a friendly invitation to new bitcoin users. Bitcoin Jesus is now preaching about the looming bitcoin apocalypse.

The viciousness and intractability of the scaling fight could suggest a flaw at the heart of bitcoin’s core democratic ideals. Maybe, in the end, we really do need authority figures to make big decisions—especially when there’s money on the line. But Charlie Shrem, another early bitcoin entrepreneur who now supports the SegWit solution, focuses on the fact that the software has stood firm amid the chaos. “Changes that can hurt the network can’t happen easily. It’s the same thing with changes that can make the network better. It’s what makes the network strong. It’s beautiful.” His opponent, Ver, sees the same silver lining.

It’s not surprising that the two would share a sanguine perspective on the chaos gripping their life’s work. Though nominally antagonists today, Shrem and Ver have a friendship rooted in years in the bitcoin trenches—Ver’s first investment was in Shrem’s bitcoin payment startup. Shrem says Ver (along with “a lot of other people who hate each other on the internet”) will attend his upcoming wedding.

In the aftermath of the exchanges’ March letter, the tension over scaling has continued to ratchet up slowly. New proposals have attempted to break the standoff between Bitcoin Unlimited and SegWit, including one that some say subverts bitcoin’s basic decision-making process. A version of the SegWit solution was successfully activated on the bitcoin alternative Litecoin, demonstrating that it’s ready for the big leagues. But still, the deadlock holds, bitcoin is left with the slow and expensive status quo, and neither side is truly happy.

And maybe that’s just what democracy looks like.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.