This article is part of Future Tense, a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University. On Wednesday, June 14, Future Tense will host a happy hour event called “What Your Dog Really Thinks of You” in Washington. For more information and to RSVP, visit the New America website.

In “Lawnmower Dog,” an early episode of the animated comedy Rick and Morty, Jerry—hapless patriarch of the Smith family—makes an ill-considered demand. Fed up with the family’s incontinent pet Snuffles, he insists that his mad scientist father-in-law, Rick, invent a device to enhance the animal’s intelligence. “I thought the whole point of having a dog was to feel superior, Jerry. If I were you, I wouldn’t pull that thread,” Rick responds with characteristic cynicism. Nevertheless, he complies, quickly cobbling together a device that endows the creature with the power of speech. Predictably, disaster ensues.

Cybernetically enhanced talking dogs are, of course, a familiar science-fictional conceit. Some such stories invite us to luxuriate in the fantasy of easier communication with our canine companions. Others, however, get at a darker reality, one that unfolds in that episode of Rick and Morty: Talking dogs would almost certainly be monstrous creations, disrupting the very things we love most about them.

The most benign talking dogs are likely those in Pixar’s 2009 film Up, a genial exploration of the ways we cobble together family from the remnants of disappointed dreams. In it, the elderly Carl travels to the secluded South American locale Paradise Falls. There, he learns that his childhood idol Charles Muntz—an adventurer who had fled to the region decades before—outfitted a pack of dogs with collars that let them speak. Before long, the golden retriever Dug befriends our aged hero, joining him in his struggle with the unsurprisingly villainous Muntz.

Though a few of Up’s chatty pups are just as bad as their original master, they still offer a largely ideal vision of canine transparency. Intelligent but not too intelligent, each member of its pack is what he or she appears to be: Doberman pinscher Alpha is a mean bully, fluffy Dug is equal parts dopey and helpful, and every member of the pack loathes both squirrels and mailmen, despite having spent their lives in a jungle where they’ve never encountered either. Their capacity for speech only underscores, and sometimes amplifies, these familiar doggy characteristics, encouraging us to believe that a dog is always going to be a dog, no matter how smart it gets.

When we imagine real-world canine communication, it’s probably the Up ideal that we have in mind. It’s not that we hope to understand their own emotions—we just need them to confirm the feelings we project onto them. We long to know that they love us in the same way we love them, and we want to hear them say so.

But even if they did feel the way we do, would they really be able to articulate it? In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein famously proposes, “If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.” That maxim is often understood as a consequence of Wittgenstein’s belief that our language intertwines with our whole form of life, emerging out of the way we move through the world. But what could we want from a talking dog if not the assurance that it contentedly fits into our form of life?

In one of its few good jokes, Woody Allen’s painfully unfunny sci-fi comedy Sleeper suggests that we probably wouldn’t get our wish. Having awoken 200 years in the future, Allen’s protagonist eventually receives Rags, a “computerized dog.” Though Rags can speak, he’s only capable of introducing himself over and over again. “Woof, woof, woof. Hello, I’m Rags,” he repeatedly announces, no matter what’s asked of him. It’s a bit that invites a possible emendation to Wittgenstein’s familiar phrase: “If a dog could speak, we probably wouldn’t be able to hold down a conversation with it.”

Other cybernetic dogs bring to mind a wholly different Wittgensteinian observation, one that points to the deep reserves of anger often concealed by inchoate attempts at communication. “Anyone who listens to a child’s crying and understands what he hears will know that it harbours dormant psychic forces, terrible forces different from anything commonly assumed. Profound rage, pain and lust for destruction,” the philosopher wrote in 1929. If we could understand a dog’s speech, would we really want to know what it has to say? The tales we tell suggest otherwise: As Jeff VanderMeer writes in a recent essay on Kirsten Bakis’ stirring novel Lives of the Monster Dogs, it’s rare to find a talking animal story that “makes readers consider the actual lives of animals, that tries to inhabit a different mode of being.”

For one example of what that “different mode of being” might entail, we could look to the Grant Morrison–written comic We3, which follows a dog, rabbit, and cat that have been turned into living weapons by the military. Though all three can speak, they do so in ways specific to—and limited by—their animal natures. The rabbit is constantly in search of food, the cat is abrasive and independent, and the dog? The dog is desperate to please. Praised for its performance by a visiting dignitary, it can only respond in kind. “Gud dog. Is gud dog?” it asks.

In this regard, Morrison’s cybernetic animals are, of course, still shaped by human perceptions and expectations, much like Up’s Dug (who is, in fact, “gud”). Here, however, those limitations are key to the story’s bleak moral rather than the expression of some underlying fantasy. We3 suggests that humans cage domestic animals by characterizing them, imprisoning them in structures of belief. Even in this fictional context, cybernetics prove an apt reference point, not least of all because they’ve always been technologies of control, at least since Norbert Wiener popularized the term in the 1940s. It’s not until Morrison’s animals are liberated from their mechanical enhancements—and all they represent—that they’re free to be themselves.

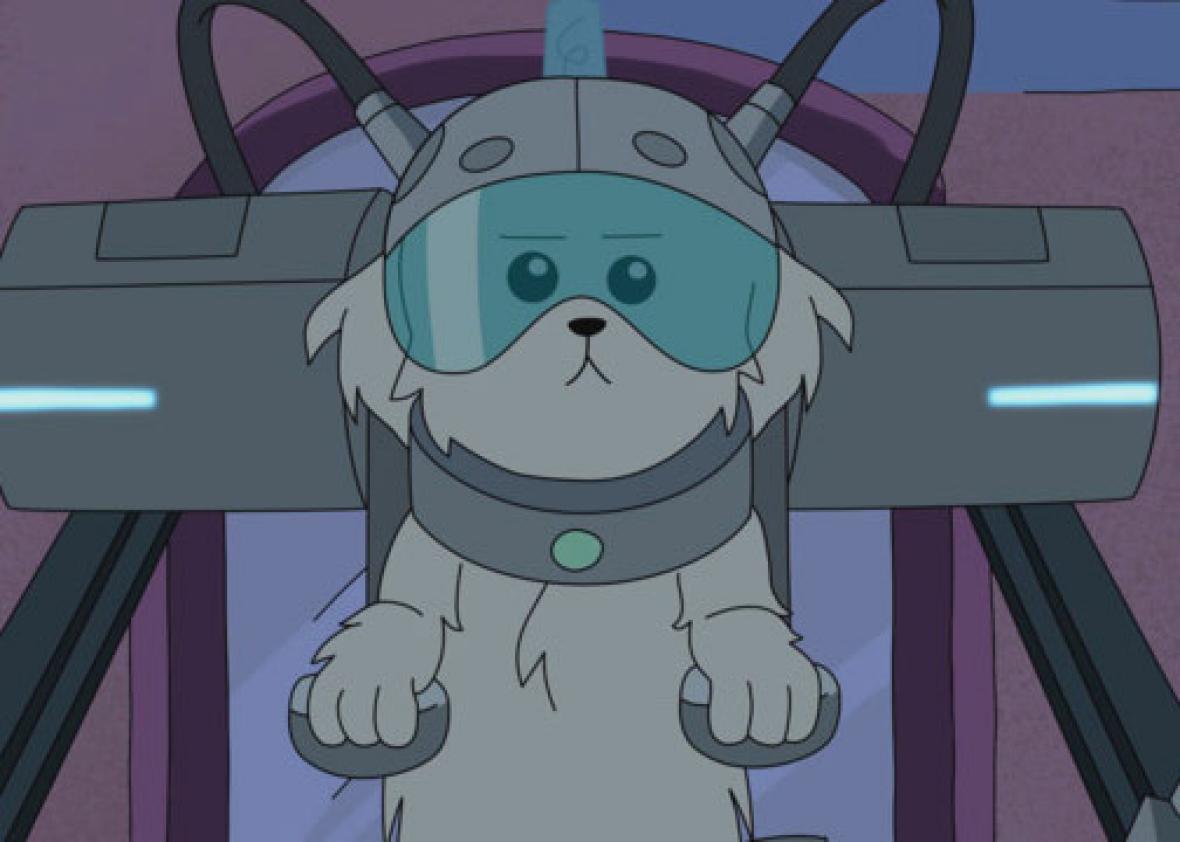

Though it does so in a satirical spirit, Rick and Morty takes this premise to a far grimmer place. With his intelligence dialed up to levels beyond that of his supposed masters, Snuffles quickly realizes how cruelly he and his kind have been treated by humans. While sitting in a powerful exoskeleton he built for himself, he interrogates Morty’s sister. “Where are my testicles, Summer?” he asks. “They were removed. Where have they gone?” Before long, he’s assembled an army of similarly intelligent dogs, an insurrectionary force plotting revenge for millennia of selective breeding. Like Wittgenstein’s crying infant, Snuffles (or Snowball, to use the title he gives himself after shedding his “slave name”) dreams only of destruction.

Goofy as it is, “Lawnmower Dog” gets at a truth limned by many other stories of cybernetic canines: It’s probably the qualities dividing us from our pets that make our relationships with them tenable. Break down those borders, and our beloved companions threaten to become something else—something that would almost certainly be far less companionable. Better, then, to let the dogs bark, yip, and growl as they may. It’s all fun and games until someone starts wondering where his testicles have gone.