Dating apps for gay men don’t have the greatest reputation. From Grindr to Scruff, Hornet to Jack’d, the digital platforms are best known for dredging up flakey users, svelte-only fat-shamers, masc-4-masc femme-phobes, and it’s-a-personal-preference racists.

Yet their scope and reach in the queer community are hard to overstate. Since the 2009 launch of Grindr, the first and most ubiquitous of the set, gay dating apps have racked up north of several-dozen million users in some 200 countries (including Cuba!). Grindr says that its users average 54 minutes on the app per day. And that seems about right: I can’t even count how many gay friends I have for whom popping open Grindr is as rote of a smartphone task as scanning their email-clogged inboxes.

Now, almost a decade after they started bringing torso pics to queer men’s devices the world over, these powerful gay platforms are trying to reach beyond their hookup origins.

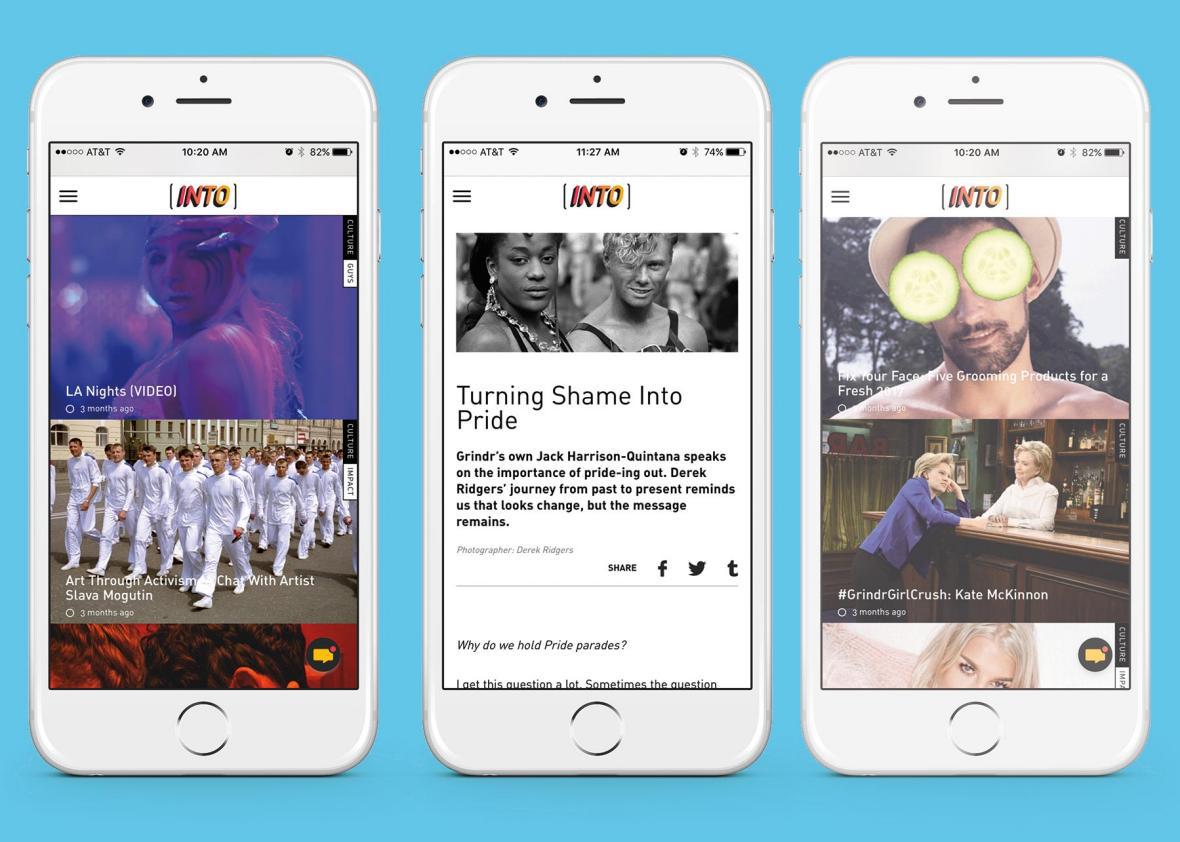

Grindr, for instance, seems to be looking to shed its scurrilous image as “just a hookup app.” In March, the company that pioneered the geolocation-based, casual sex–facilitating sensation launched the online magazine Into. CEO Joel Simkhai told Forbes in a recent interview that “millions of Grindr users [were] asking us to figure out what’s going on around them,” so the company decided to start curating culture-minded content. While it’s still early days, the publication seems to represent an earnest effort to re-envision the Grindr brand. It’s hired a serious editor in chief. It’s published a buffet of articles, photography, and videos that cater to a variety of identities and interests. And it’s putting out more than just fluff by featuring topics such as the one-year remembrance of the Pulse nightclub shooting, the “resist march” at Los Angeles Pride, Ireland’s first openly gay prime minister, and the record levels of violence against LGBTQ people in 2016.

Grindr isn’t the only gay app getting in on the rebranding game. Scruff, which leans just a touch toward the “bear”—or husky, hirsute—crowd, has started helping host parties and Pride events across the planet. From the French Alps to New Delhi, it’s encouraging revelers to use gayness as an entry point through which they can traipse to faraway places. The gay social-networking app Hornet, too, has been hosting live events. Just this month, it put together a group of LGBTQ media gurus in New York for Loud & Proud, a sold-out panel discussion that centered around the importance of inclusion in a diversifying media world.

Such moves make good sense. Lots of queer men power up their gay app of choice when they go out or arrive in a new city in hopes of finding people who might be navigating similar life experiences. With open events and publications, these companies get to put their brands on a wider variety of gay connections. And, in doing so, the likes of Grindr, Hornet, and Scruff are re-creating queer sociability in significant ways.

These apps, on the one hand, still allow queer men the messiness of exploring our identities. We can cruise furtively through rows of profiles, eking out a string of flirty chats or just going for some unembellished, anonymous sex. Especially for people who might be deeply closeted or marooned in bigoted communities, these services offer keys for investigating what may initially seem like errant feelings of homosexuality. In many respects, this isn’t too different from the late 1990s, when online chatrooms cracked open a universe for curious queers that had previously been mired in mystery.

What perhaps sets these new brands apart from their predecessors, then, is their push to expand the visibility of the queer community. For instance, one user might not know much about another offline, but he might know little things about him from having scrolled through his geotagged social media page. He might even recognize him from his profile photos walking down the street, or in the audience of, say, a recent panel about digital content by and for the queer community. Far from keeping queer men on the fringes, these apps are fueling a novel knowingness among users—on the app, yes, but also offline, when users go out to create and engage with open communities. These apps are playing host to conversations—silent and verbal, private and public—about what, exactly, the queer experience can entail. They’re helping, in other words, make the connections so many queers have been yearning for all along.

This isn’t to suggest that having an out presence in public spaces is the only thing that matters for strengthening the community, especially when vulnerability often attends visibility. But there’s power in being able to meet, forge connections, take up space, and simply point queer people to gatherings of all different forms and shapes.

Sound familiar? At a time when—for reasons like rent, warming attitudes toward the queer community, and technology—gay bars are disappearing, apps are trying to offer the sorts of interactions that reproduce many of the same historic functions. They appear to be reconceptualizing spaces that have historically been bulwarks against anti-gay bigotry; spaces where one can, at least to a degree, enjoy being in public without mainstream judgment.

Digital dating platforms aren’t just taking building their own branded communities, though. They’ve also started to move into advocacy.

Hornet, for instance, has been trying to combat the persistent stigma around HIV by providing its users with health facts through various public events and by educating them about HIV prevention. Grindr, too, has been tapping its extensive user base for public health awareness campaigns. In 2015, it conducted a survey with the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and Centers for Disease Control to gauge its users’ awareness of PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis), a daily regimen that can protect users from contracting HIV. The company also participated in a University of California, Los Angeles, study that showed using the app to push banner ads and notifications for free HIV home test kits was an effective way to reach high-risk populations. It’s a fitting role for apps whose original purpose unquestionably (and unavoidably, given that stigma still forces many men into silence about their health status) contributes to sexually transmitted disease transmission.

The companies are activating their networks for political action, too. Earlier this year, Grindr users might remember seeing in-app notifications about targeted violence against gay men in Chechnya. The pro-Kremlin government in the long-contested region had begun rounding up and abusing dozens, if not hundreds, of alleged homosexual men. Chechen authorities tortured some to death. They involuntary outed many others to their families in a region where the sexual orientation is considered taboo. Grindr for Equality, the app’s advocacy arm, and the Russian LGBT Network, a St. Petersburg–based gay rights group, worked together at the height of the crackdown in April to distribute updates, as well as a hotline number and email addresses for aid and evacuation assistance, via the app. It’s difficult to know whether the outreach had much impact on the ground. But the actions were still remarkable—a hookup app as a source of political power while other nations, most notably the U.S., declined to act.

Of course, these companies aren’t addressing all of the issues facing LGBTQ individuals today. For starters, the apps don’t seem to be looking to jettison their most infamous features. Users still have to deal with trolls and prejudices along various axes. (“Hooking up with a black guy is on my bucket list,” a Grindr user wrote to me once, sans irony.) It’s still an open question as to what it might mean that companies are trying to monetize these connections. Their effect on the character and shape of the queer community has yet to fully play out. And, naturally, men can still look for, and probably find, more intimate connections to ease queer loneliness elsewhere.

But as these apps widen opportunities that cut across the queer community—organizing a range of parties, health awareness events, professional seminars, Pride parades, and political campaigns—I hope that they’ll also, eventually, afford queer men of all stripes something too often denied to us: the ability to take up more space and to do so on our own terms.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.