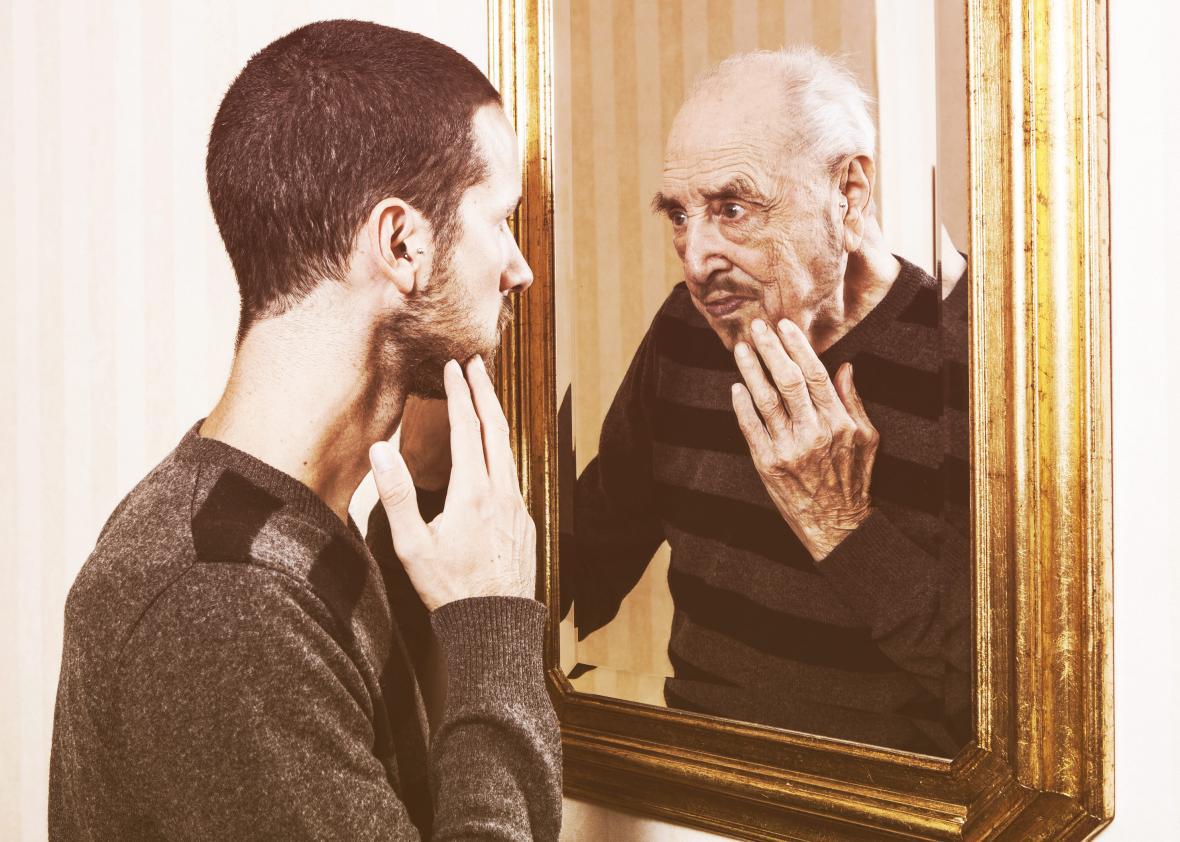

Our future selves are strangers to us.

This isn’t some poetic metaphor; it’s a neurological fact. FMRI studies suggest that when you imagine your future self, your brain does something weird: It stops acting as if you’re thinking about yourself. Instead, it starts acting as if you’re thinking about a completely different person.

Here’s how it works: Typically, when you think about yourself, a region of the brain known as the medial prefrontal cortex, or MPFC, powers up. When you think about other people, it powers down. And if you feel like you don’t have anything in common with the people you’re thinking about? The MPFC activates even less.

More than 100 brain-imaging studies have reported this effect. (Here’s a helpful meta-analysis—while some fMRI studies have been called into question recently for statistical errors and false positives, this particular finding is robust.) But there’s one major exception to this rule: The further out in time you try to imagine your own life, the less activation you show in the MPFC. In other words, your brain acts as if your future self is someone you don’t know very well and, frankly, someone you don’t care about.

This glitchy brain behavior may make it harder for us to take actions that benefit our future selves both as individuals and as a society. Studies show that the more your brain treats your future self like a stranger, the less self-control you exhibit today, and the less likely you are to make pro-social choices, choices that will probably help the world in the long run. You’re less able to resist temptations, you procrastinate more, you exercise less, you put away less money for your retirement, you give up sooner in the face of frustration or temporary pain, and you’re less likely to care about or try to prevent long-term challenges like climate change.

This makes sense. As UCLA researcher Hal Hirschfield put it: “Why would you save money for your future self when, to your brain, it feels like you’re just handing away your money to a complete stranger?”

Our current political climate in the United States reflects this same cognitive bias against the future. Recently, President Trump signed a sweeping executive order undoing a vast array of regulations designed to mitigate long-term climate change in favor of policies that provide much shorter-term economic benefits. And Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin recently made headlines when he said publicly that he is “not worried at all” about the possibility automation could eliminate millions or even tens of millions of American jobs in the future. “It’s not even on our radar screen,” he said, adding that it won’t happen for “50 to 100 years or more.” But, as Daniel Gross wrote in Slate, he’s wrong. It probably will not take five decades or more for robots and artificial intelligence to significantly reduce the number of jobs available to Americans. Recent economic research from MIT suggests that 670,000 industrial jobs have already been lost to automation in the U.S.

But even if did take 50 years for this hurricane to hit the workforce, are we really comfortable with our leaders pushing off the problem to our future selves? According to the latest census, nearly 180 million Americans alive today should expect to still be alive in 50 years. Are we not in the least interested in thinking about what kind of world we might find ourselves in, or want to help make or avoid, when that time comes?

Unfortunately across America, thinking about our far-off future is not a habit that most people come by easily or practice often. I’m a research director at the Institute for the Future, a nonprofit based in Palo Alto, California, where we just completed the first major survey of future thinking in the United States. In it, 2,818 people reflected on how frequently they imagine something that might happen or something they might personally do at different timescales of the future. (Respondents were 18 or older, and there is a margin of error of ±2 percentage points and a 95 percent confidence level.)

The survey found 53 percent of Americans say they rarely or never think about the “far future,” or something that might happen 30 years from today. Twenty-one percent report imagining this future less than once a year, while the largest group of respondents, 32 percent, say it never crosses their mind at all.

Likewise, 36 percent of Americans say they rarely or never think about something they might personally do 10 years from now. The largest group of respondents, 19 percent, think about this 10-year future less than once a year, while another 17 percent say they never think about it at all.

Fortunately, five-year thinking is a bit more common than 10- and 30-year thinking. Just 27 percent of respondents rarely or never think about their lives as far as five years out. The most common answer to, “How often do you think about something that you might do or that might happen five years from now?” was once or twice a month. But compared with how often with think about our close friends and family—a near daily occurrence—we hardly give our own future selves a thought.

The survey suggests that the older you get, the less you think about the future—75 percent of seniors rarely or never think 30 years out, while 51 percent rarely or never think 10 years out. A common response, of course, was: “I don’t expect to be alive then, so I don’t think about it.” But previous neurological research has also shown that imagining the future simply becomes more difficult as we age. We lose gray matter in and connectivity across regions associated with mental simulation of the future.

The data showed that having children or grandchildren did not increase future thinking. However, one life event did: a brush with mortality, such as a potentially terminal medical diagnosis, a near-death experience, or other traumatic event. This was associated in the survey data with a statistically significant increase in weekly future thoughts at both the five- and 10-year timelines (but not at the 30-year timeline). This makes sense: Brushes with mortality are often associated, in the psychological literature, with a renewed effort to lead a meaningful life and leave a positive legacy behind. Thinking about, planning for, and contributing to our shared long-term futures may be an essential part of laying the groundwork for both.

Even without a brush with mortality, some people are very future-minded. Seventeen percent of Americans say they think about the world 30 years out at least once a week. Nearly one-third, or 29 percent, think about the 10-year future at least once a week. And slightly more (35 percent) think about the five-year future at least once a week. The fact that some people regularly “check in” mentally with the future aligns with something researchers have previously discovered: People have different thresholds for when they view a future self as a stranger. For some people, their MPFC powers down when thinking about a future self a year from now; for others, the switch doesn’t happen until “future you” is five, 10, or 15 years out. It’s not clear from the present data whether thinking about the future regularly can change the brain’s behavior or whether people who have a higher threshold just naturally enjoy thinking about the future more, because they already relate better to their future selves.

Either way, this leaves us with a kind of “future gap” in America.

Some people regularly connect with their future selves, but a majority does not. And this matters, beyond the links between future thinking and greater self-control and pro-social behavior. Thinking about the five-, 10-, and 30-year future is essential to being an engaged citizen and creative problem-solver. Curiosity about what might happen in the future, the ability to imagine how things could be different, and empathy for our future selves are all necessary if we want to create change in our own lives or the world around us.

If you are someone who rarely thinks about the future, it’s a surprisingly easy habit to adopt. In the course I teach at Stanford University’s continuing studies program, “How to Think Like a Futurist,” I tell students: Make a list of things that you’re interested in—things like food, travel, cars, the city you live in, shoes, dogs, music, real estate. Then, at least once a week, do a google search for “the future of” one of the things on your list. Read an article, listen to a podcast, watch a video—and get some specific ideas of what the future of something you care about might be like.

No one can predict the future, but plenty of people are out there talking about what the future could be—with new technologies, new policies, new culture. And when you can imagine concrete details of a possible future, it’s easier to close the future gap and put yourself into that future. Future you becomes less of a stranger—and someone you can actively conspire on behalf of to create a better world and a better life.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.