Ownership of Internet of Things devices, digital rights management law, interminably long software click-through agreements—these are all modern issues that seem to be a consequence of new technology. Indeed, questions of technological ownership are on the cutting edge of the law, with the Supreme Court set to consider those questions in the Impression Products v. Lexmark International case argued recently, a case over printer ink cartridges that has potential implications for emerging technologies like cars and automatic cat feeders.

Some contend that “complexity of the modern contracting markets” requires new rules of ownership, but history shows that this question is not so modern. In fact, one of the earliest fights over ownership of technology occurred a century ago, involving a device that was strikingly novel for its time: the movie projector. It’s worth revisiting what happened in those early days, because the strategies that companies use today to control what you can do with the products you own are remarkably similar to those that the early motion picture industry once employed. The reaction to and fallout from those earlier practices shed much light on how we should react today.

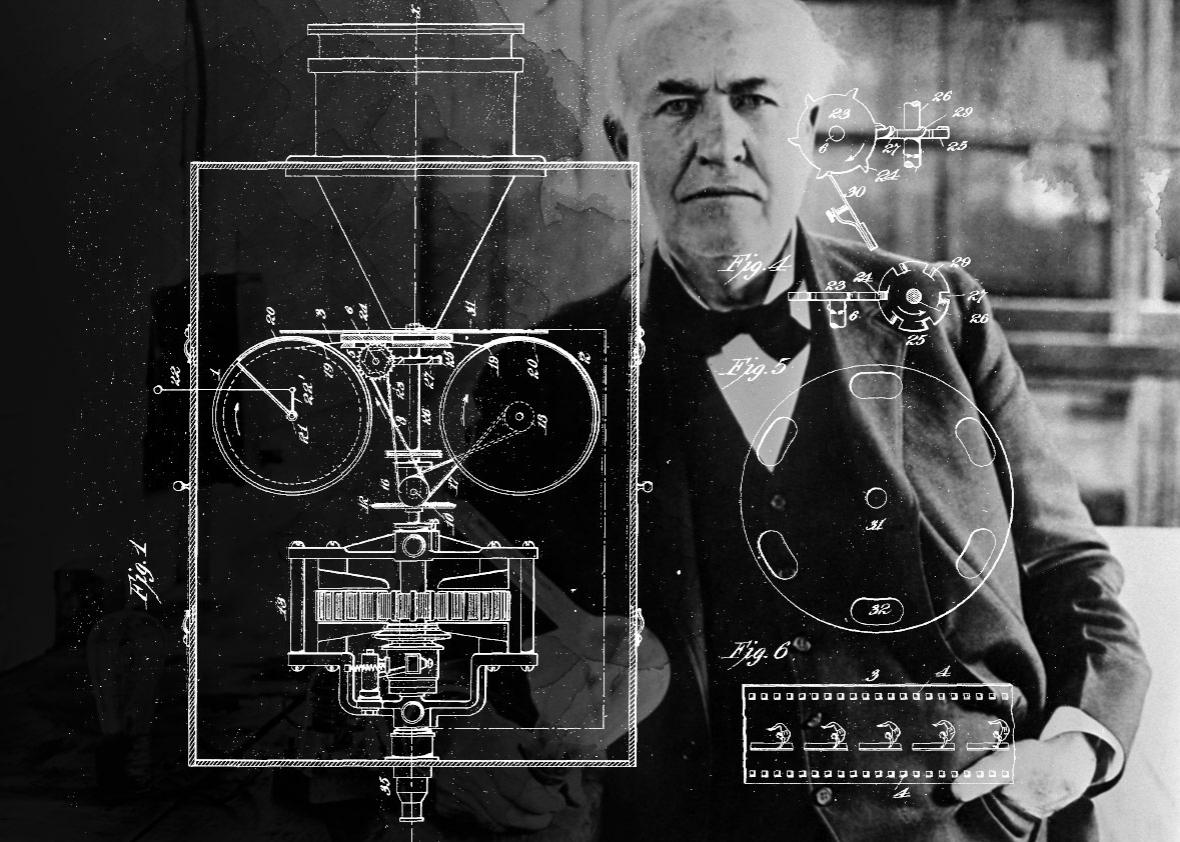

Motion pictures are complicated things with multiple parts, largely invented around the turn of the 20th century. As with other multicomponent inventions, different people invented each of the parts, and different companies owned the patents.

After a period of infighting, in the fall of 1908 the companies joined forces to use those patents to dominate the fledgling motion picture industry. Thomas Edison, who held the patent to the motion picture camera (the “Kinetograph,” he called it), engineered the arrangement, which would be operated by a corporation called the Motion Picture Patents Co. The story of that company is recorded in a published trial record from the early 20th century, later summarized in a 1959 article by professor Ralph Cassady Jr.

As Cassady explains, the Patents Co. controlled every aspect of the motion picture industry. Undeveloped film could only be sold to licensed filmmakers. Filmmakers could lease, not sell, the produced reels only to licensed distributors. Those distributors, called “exchanges” at the time, could distribute only to licensed movie theaters—until 1910, when the Patents Co. opened its own exchange and eliminated nearly all the other exchanges.

And, most importantly, any theater that purchased a projector had to agree to license terms, stamped on a plate attached to the projector, that the theater would only show licensed movies on that projector and would comply with “other terms to be fixed by the Motion Picture Patents Company.”

This license term is the textbook example of subverting traditional concepts of ownership. Imagine if you bought a picture frame that could only house photographs taken with a certain camera, or a box of pasta that could only be cooked with approved sauces.

Or an ink cartridge that could not be refilled but with approved ink. A century later, that’s the situation that gave rise to the new Supreme Court case. Lexmark sells its ink cartridges with a license sticker, prohibiting buyers from refilling the cartridge or reselling the cartridge to anyone other than Lexmark. Lexmark argues that patents on the cartridge make the license sticker enforceable, allowing the company to stop a company like Impression Products, which refills those cartridges without authorization. The Supreme Court will likely decide the Impression Products case in the next few months. And if the justices look back to the history of motion picture patents, they will undoubtedly reject Lexmark’s theory.

In fact, it was largely the Patents Co.’s overreaching attempt to control use of products after sale that was the downfall of the scheme. In 1915, a theater company that owned a film projector—license notice plate and all—obtained two reels from the Universal Film Manufacturing Co. The reels themselves were manufactured legally because the patents on film had expired, but Universal Film was not a licensee of the Motion Picture Patents Co. On the very day that the theater company showed the unauthorized reels, the Patents Co. sued. In 1917 the case reached the Supreme Court as Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Universal Film Manufacturing Co.

The problem for the Patents Co. was that the theater company owned the projector, and according to the Supreme Court, owners of devices generally get to use the things that they own. The idea that the Patents Co. could use patent law to control use of devices after sale was apparently frightening to the justices, who wrote that such a tool of control could be the “perfect instrument of favoritism and oppression.” The “cost, inconvenience and annoyance to the public” of allowing the Patents Co. to dictate what movies could be played on projectors led the Supreme Court to decide against the Patents Co.

Fast-forward from 1917 to 2017, and we’re seeing that “instrument of favoritism and oppression” coming fully into use. In 1992, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, a court known for leaning in favor of patent owners, decided to ignore the Supreme Court’s Motion Picture Patents Co. decision and allow for these sticker licenses to be enforced through patent law, in a case titled Mallinckrodt v. Medipart. Since that ruling, numerous companies have sought to wipe away ownership rights in order to maintain control over their products. Besides Lexmark’s ink scheme, Keurig tried to force its customers to use only Keurig K-Cups, and the new Juicero juicer will only squeeze authorized fruits, based on a QR code printed on the produce.

Lexmark, for its part, argues that the restrictions on its ink cartridges benefit consumers, because the restrictions allow Lexmark to sell cheap printers and make money off of its one-time-use ink cartridges. It may sound compelling, but there are a couple of reasons to be skeptical of this line of thinking.

First, in the Motion Picture Patents Co. case, the Supreme Court rejected the exact same argument, almost word for word. The Patents Co. contended that “the public is benefited by the sale of the machine at what is practically its cost,” where the seller “makes its entire profit from the sale of the supplies”—precisely what Lexmark does. The Supreme Court roundly rejected this practice, because of the excessive power it would give to sellers. And more importantly, that excessive power can lead to devastating situations of monopolistic control—precisely what the Patents Co.’s own behavior teaches.

Though the Patents Co. pulled the strings on a substantial part of the motion picture industry, there were still independents who refused to pay tribute. The Patents Co. cracked down hard on these independents. It launched numerous lawsuits, but also apparently engaged in moblike bullying tactics including threats of violence, raids for bootleg film reels, and even a secret force of spies, as reported by film historian Terry Ramsaye. (The Cosa Nostra nature of the Patents Co. applied within its ranks, too. William Fox, founder of the Fox empire, ran a licensed film exchange, which the Patents Co. wanted to acquire. When Fox refused to sell, the Patents Co. reportedly bribed a projectionist to send Fox’s reels to a “house of prostitution in Hoboken” and then canceled Fox’s license on the grounds that he had allowed films to be used for immoral purposes.) It is sometimes said that, in an effort to avoid the strong-arm enforcers of Edison and the Patents Co., these independent film businesses moved as far away from Edison’s home base in New Jersey as possible—to a then–lightly populated town called Hollywood, California.

Were the Supreme Court to change course in the Impression Products case and allow patent owners the degree of control over products that the court once denied, we can expect to see this sort of aggressive monopolization crop up again. Undoing the Motion Picture Patents Co. decision would embolden companies to build up bigger and more powerful monopolies to control the technologies we all use today—just as the Patents Co. was emboldened to dominate the fledgling film market until the Supreme Court stopped it.

As I’ve written before, diminishing ownership rights over consumer products cuts off innovation upon those products. That’s evident in the motion picture industry history, too. The Patents Co. itself, which spent so much time focusing on maintaining control over the industry, ultimately collapsed upon itself, the victim of executive infighting and a government antitrust action. The independents, on the other hand, were forced to innovate to maintain competitiveness. Independents reportedly developed the feature-length film format, new distribution arrangements, and promotional strategies like the Hollywood star system. Cassady called the independent industry “revolutionary in nature” and “a new era in motion picture production and distribution.”

Between the parties to Motion Picture Patents Co. v. Universal Film Manufacturing Co., the topside company, once the puppet master of the film industry, is no more. But the Universal Film Manufacturing Co., once the rogue distributor, would continue to expand production capabilities, even to this day. It is now better known by its new name: Universal Studios.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.