On a recent Saturday, a squad of Lego robots fitted with markers limped, hopped, and spun dizzily across the table. Some flipped over or trailed broken Lego limbs as they covered butcher paper with ragged squiggles. But the kids who were building and programming these bots weren’t deterred. They made repairs and tweaked their code. A similar persistence was on display at nearby tables where groups of young people created computer games and websites.

The freedom to mess up, repeatedly, is a core appeal of this club known as CoderDojo, a loosely connected global network of coding workshops for kids ages 6 to 18, including this Boston outpost that meets in the borrowed offices of the tech company LogMeIn.

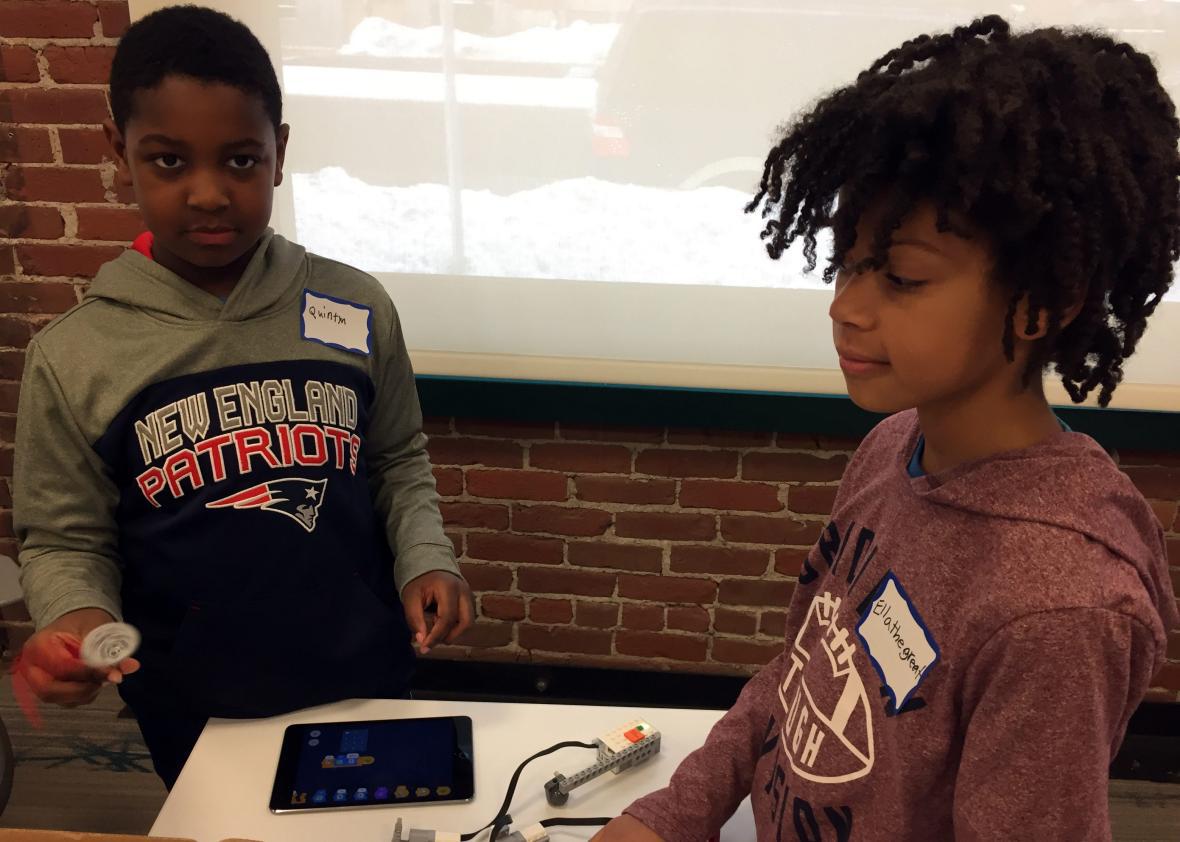

“You can make your own design. You don’t have to follow a book or listen to anybody tell you what to do,” 9-year old Ella Bartholomew said while inspecting her robot. “You can just program it the way you want it.”

This freewheeling atmosphere isn’t for everybody, but it has fueled a movement. The CoderDojos are free and volunteer-run, and from a single club started by a teenage Irish hacker in 2011, they’ve managed to grow into more than 1,200 dojos in 65 countries and counting. Rather than teach a specific programming curriculum, the overarching goal of CoderDojo is to spark a passion for coding.

Before James Whelton founded CoderDojo as an 18-year old in Cork, Ireland, he had gained global tech fame for hacking the iPod Nano. Whelton’s notoriety made friends and classmates eager to learn more, so he started an after-school coding club. Then, after speaking about his hack at the Dublin Web Summit, Whelton met Bill Liao, a venture capitalist with SOSV, who convinced him to think bigger.

The pair launched the first CoderDojo in June 2011, hosted by the National Software Centre in Cork. They called it a dojo (the term for a Japanese martial-arts training center) to indicate it was a place for learning but distinct from a school with grades, tests, and regimented teaching. Kids at CoderDojo were encouraged to jump straight into their own coding projects while tech-savvy volunteers circulated among them, ready to help when needed. Within a year, there were 100 more dojos in Ireland and beyond.

Chris Berdik

The club is engineered to spread. In active online forums, members of the CoderDojo community share project ideas, post resources in multiple languages, and offer advice for anybody, anywhere to start their own dojos.

“CoderDojo is open-source, meaning people support and contribute to the project just like developers can contribute to open-source software,” said Ross O’Neill, the lead community liaison of the CoderDojo Foundation, established in 2013 to manage the club’s rapid growth.

The starting point for most dojos is the programming language Scratch, which uses stackable, color-coded digital block commands rather than the precise, keyed-in syntax of text-based code. Beyond Scratch, some dojos focus on web development codes such as HTML or CSS, while others have kids programming apps, games, 3-D models, or robots.

“It’s a very flexible model,” said O’Neill. “You take the overarching concept and bring it into your community, and every dojo is its own entity and has its own identity.”

For example, while some dojos don’t formally track growth in coding skill, a few have experimented with a karatelike “belt” system to do just that. Most dojos meet in borrowed office space or community centers, but a dojo in Madagascar reaches remote towns with a fleet of buses stocked with laptops and volunteers from universities in the capital city, Antananarivo.

The director of information systems for Madagascar’s ministry of culture, Andry Ravololonjatovo, also serves as the communications officer for the “CoderBus” initiative. Reached by Facebook Messenger, Ravololonjatovo explained that most kids who board the buses have never touched a computer before.

“We just inspire the kids with the superpowers, the possibilities with coding,” he wrote. “At least, they would have tasted it, even if they don’t have computers at home. They will eventually find a way by themselves to continue studying programming.”

Indeed, the primary goal of CoderDojo is to get kids engaged with computer science as a fun and creative outlet, according to Ruma Singh, who runs the dojo in Round Rock, Texas, outside Austin. Singh’s daughter Garima founded the dojo as a high school junior (she’s now at Yale University), a year after she reluctantly took computer science at school and fell in love with it, much to her surprise. Recalling her previous negativity about programming and how few girls were in her computer science class at school, Garima was eager to get girls interested in coding early. According to a 2016 survey by the CoderDojo Foundation, nearly one-third of all dojo attendees are girls, and about the same proportion of mentors are female.

Some parents drive more than an hour to take their children to Round Rock’s CoderDojo. Free admission is a big draw, but so is the absence of curriculum, said Singh, “because parents know that their children aren’t missing anything if they’re not able to make every meeting.”

Still, not everybody loves the unstructured approach. According to Kyle Silberbauer, an engineering manager at LogMeIn who leads the dojo that his company hosts, “the families and the volunteers who want that clear lesson plan that directs kids from step to step don’t stick around.”

One parent at the Boston dojo admitted that she’s had to adjust to the chaos. Denise Haynes watched her 8-year old son Quintyn bounce between robots and Scratch. “He gets to hang out with his friends. They’re having fun and using their brains,” she said. “But I want to know, what is he supposed to learn? Even this morning, I’m like, ‘Quintyn, did you practice?’ He said, ‘I don’t have to practice, mommy, people come around and help us.’ And I said, ‘Oh, OK.’ ”

Chris Berdik

Of course, mentors will suggest projects for the youngest kids making their first visits to the dojo, noted Ron Yang, a doctoral student at Harvard Business School and the lead Scratch mentor. “It can be hard for younger kids to sit down and focus and learn the basics by themselves if they don’t have a reason,” said Yang. “But after one or two sessions, you notice the kids start getting excited, and they get lots of ideas about what they want to do.”

Toward the end of the 90-minute CoderDojo session, Yang announced that it was time for kids to show off what they’d coded, if they wanted to, by walking to the front of the room and plugging their laptops into a projector.

“OK. Let’s see who’s ready, and we’ll get started,” Yang called out. “Who wants to do the first demo?”

Several small hands shot into the air.

This story was produced by the Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about Blended Learning.