I called up Charles Delavan because I thought he was lying.

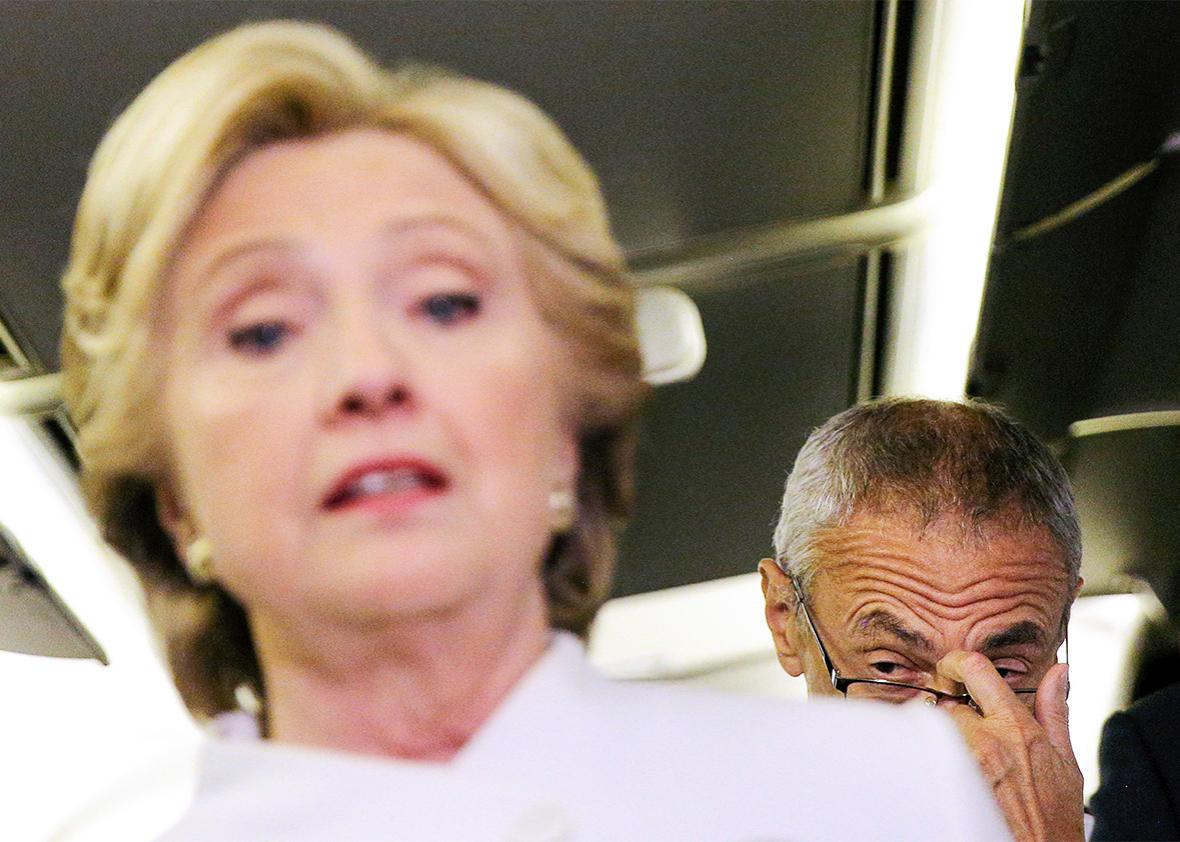

Delavan, 29, has achieved a measure of infamy among politicos and security wonks as the IT guy who assured John Podesta that a phishing email intended to steal his Gmail password was “a legitimate email.” The detail emerged in an October WikiLeaks dump and was reported as a stunning example of incompetence on the part of the Hillary Clinton campaign’s tech team. Podesta or one of its aides, it seemed, had initially been suspicious of the email but went ahead and opened the fateful link after Delavan vouched for its authenticity.

But a front-page New York Times article published Tuesday gave the story an almost incredible twist. The Times quotes Delavan as saying that he actually recognized that the email was a hoax—but mistakenly typed the word legitimate when he meant to type illegitimate. The implication was that the Clinton campaign was compromised not by incompetence, but by a slip of the fingers. The anecdote triggered headlines around the web: “A Typo Might Have Cost Clinton the Election,” gushed the Week.

The Times appears to take Delavan at his word. But a close read of the email chain itself raises some obvious questions. See for yourself. Here is the original email to Podesta, purporting to be from Google:

*Subject:* *Sоmeоne has your passwоrd*

Hi John

Someone just used your password to try to sign in to your Google Account john.podesta@gmail.com.

Details: Saturday, 19 March, 8:34:30 UTC

IP Address: 134.249.139.239

Location: Ukraine

Google stopped this sign-in attempt. You should change your password immediately.

CHANGE PASSWORD

Best,

The Gmail Team

And here is Delavan’s reply to Sara Latham, Podesta’s chief of staff, who had forwarded it to him without comment.

Sara,

This is a legitimate email. John needs to change his password immediately, and ensure that two-factor authentication is turned on his account.

He can go to this link: https://myaccount.google.com/security to do both. It is absolutely imperative that this is done ASAP.

If you or he has any questions, please reach out to me at [redacted]

If Delavan had meant to type illegitimate rather than legitimate, why did he preface it with the article a rather than an? Was that a typo, too? Moreover, if Delavan’s goal had been to warn Podesta that the email was a scam, you’d think he would have told Podesta not to follow its instructions and not to click on the “change password” link therein. Instead, he followed his assertion that the email was “legitimate” by reiterating to Podesta the instructions contained in the email itself, almost to the word. The phishing email told Podesta, “You should change your password immediately”—which is exactly what Delavan told him. So Delavan not only called the email “legitimate,” he practically ordered Podesta to do what it said.

All of which led me immediately to suspect something rather uncharitable of Delavan: that he not only fell for the phishing scheme but that he subsequently lied about it to the New York Times, perhaps trying to pass it off as a typo because he was too embarrassed to admit the truth. (A quick search of Twitter made it clear that I was not the only one who suspected this.)

I doubted I could actually get a hold of Delavan to confront him with my hypothesis. I figured he would have retreated from the public internet months ago. Still, I figured it was worth a shot. The first thing I tried was to call the cellphone number contained in his email itself, which is still publicly available on WikiLeaks’ site. He picked up on the second ring.

Asked about the a/an discrepancy, Delavan told me the Times had the wording wrong. Delavan had actually meant to type that it was “not a legitimate email,” but mistakenly omitted the word not. Are you sure, I asked? “Yes,” he said. I asked why, if Delavan knew the email was not legitimate, he still directed Podesta to change his password, which is how the hackers obtained it. Delavan said he recommended the password change “out of an abundance of caution,” even though he knew the request was a scam.

It’s true that changing one’s password and enabling two-factor authentication, which Delavan also recommended to Podesta, is generally good practice if you’re concerned about hacks. And Delavan noted to me, accurately, that he included in his email a link to Google’s genuine password-change site, which would not have stolen Podesta’s credentials. But why, I asked him, didn’t he tell Podesta explicitly not to click on the link in the email? Wasn’t that the most important message to convey, if Delavan knew it was a phishing link?

“You know, I mean, hindsight being 20-20, absolutely that’s something I should have said in that email,” Delavan told me. Indeed, he had instructed many people not to click links in suspect emails over the course of the campaign. But in this case, he overlooked it. “I guess I just thought the most important thing was to go to the link I had sent, make sure to change the password, and turn on two-step verification.”

Since his mistake had been made public, Delavan told me, he’s received countless angry emails, tweets, and phone calls, and on one occasion a stranger hurled insults at him as he walked down the street near his Brooklyn apartment. He is now unemployed, and he wonders whether potential employers are avoiding him after Googling his name. “I’m sitting here and, as I’m applying for jobs and trying to figure out the rest of my life, I’m wondering, ‘Is this something that’s going to haunt me the rest of my life?’ ”

I took it from this that Delavan had been fired by the campaign for his mistake. No, he said: He had continued to work for Clinton in the same capacity right up until the campaign ended. When I sounded surprised, he pointed out that he had worked in IT for many years and had been a trusted part of the campaign’s tech staff, aside from the obvious slip-up. “The fact of the matter is that there are hundreds of success stories that aren’t going to get published,” he said. “This is one of those little things—well, obviously it’s a big thing. But there’s a reason people felt free to contact me when things went wrong. I was known as competent, responsive—all of the things that this makes me not look.”

Delavan sounded like a nice guy. He also sounded harried and a little nervous, understandably. I wanted to believe him that it was a typo, even though I wasn’t sure exactly why it mattered. But I still wasn’t sure I did. Is it possible, I asked, that you’re misremembering? Is your memory of sending that email at all hazy? No, he said. If I were to look at similar messages he had sent around that time to other staffers getting phished, Delavan told me, I would see that they said, “This is not a legitimate email.” Unfortunately, he said, he can’t prove it, because “they would have all been deleted.”

Was there any lesson he could take from all this? “I don’t know,” Delavan said. “I guess I would say double-check before you … I don’t know. I don’t know.”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.