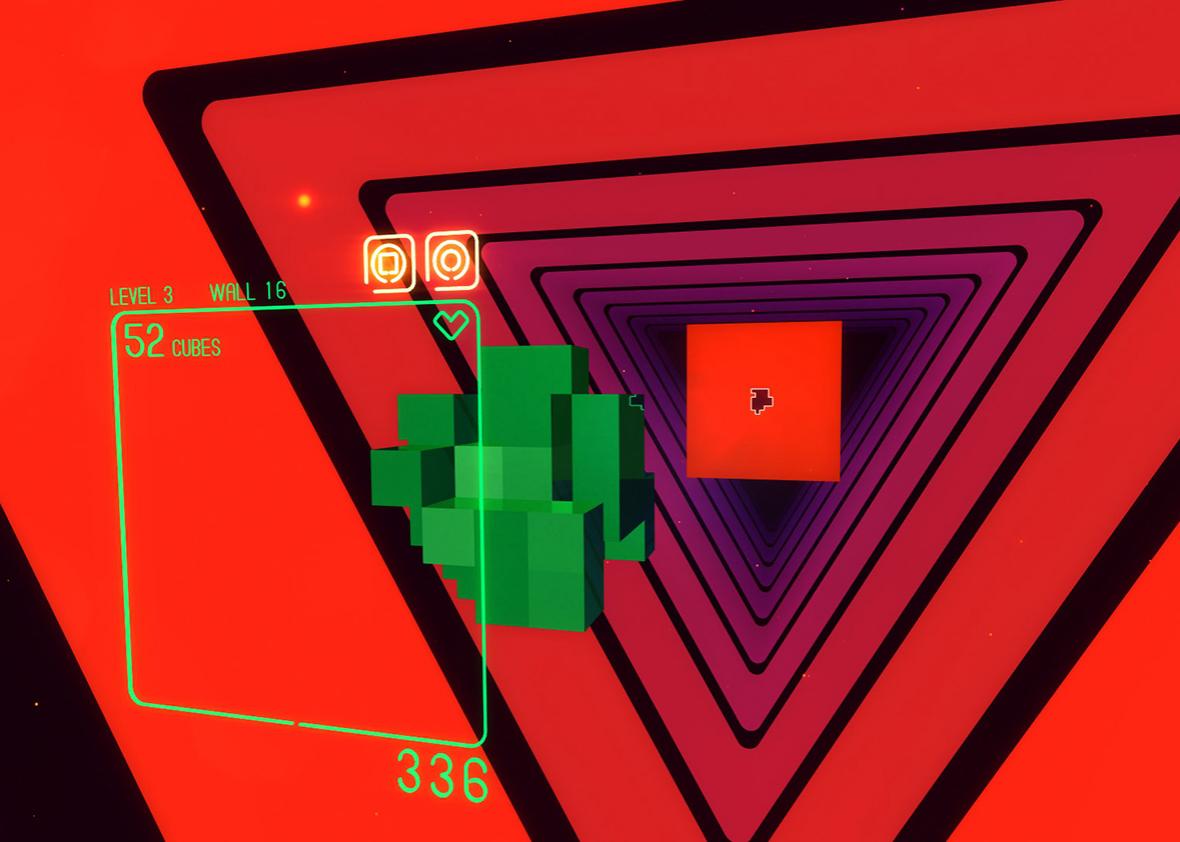

There’s something comforting about the new virtual reality game Super Hypercube. Set in a radiant, abstract world of neon light, it asks you to rotate a cluster of blocks and slot it perfectly through a corresponding hole in an advancing wall. If Tetris was, on some level, a game about cleaning up—making blocks vanish through sheer organization—then Super Hypercube is the puzzle game equivalent of those “oddly satisfying” pictures of things fitting perfectly inside other things. It’s an affirmation that if only in some small and geometric way, all is right with the world and everything is falling into place.

One of the debut games for the PlayStation VR, Sony’s recently released virtual reality headset, Super Hypercube is also one of its most pleasurable. While the PSVR’s roster of titles is full of spectacular immersive experiences like the space shooter EVE Valkyrie or the soaring Eagle Flight, Super Hypercube is the closest thing yet to a virtual reality Tetris, a puzzle game so simple, intuitive, and satisfying that you find yourself wanting just one more game—and then another.

One reason Super Hypercube is so polished is that the glittering puzzler’s creative team, Kokoromi, holds an unusual advantage: It’s been working on Super Hypercube since 2008, years before virtual reality as we know it even existed. “When we developed the original version of Super Hypercube, we weren’t thinking, ‘Let’s make a VR game!’ ” Kokoromi co-founder Heather Kelley told me. The team originally created the game as a playful art installation for an experimental gaming event in Montreal; in the absence of real VR goggles, its 3-D head-tracking glasses were crafted from LEDs, a Nintendo Wii controller, and a hot-glue gun.

For decades, virtual reality has been a technological fantasy on the cusp of reality. But despite numerous attempts to bring VR to a broader audience, it has never managed to make its way into living rooms en masse. Now, thanks to a new wave of headsets that can finally deliver the immersive thrills promised by science fiction—and particularly the PSVR, with its comparatively low $399 price tag and compatibility with the PlayStation 4 console—VR has its best shot yet at going mainstream.

For Kokoromi—whose name comes from the Japanese word for “experiment”—it means that an avant-garde puzzle game can finally make its way to the masses as well. “The technology finally caught up to us,” said developer Phil Fish.

Full of incandescent starscapes and tunnels striated with rainbow light, Super Hypercube radiates with a sleek, stylish sense of nostalgia reminiscent of ’70s and ’80s science fiction. It’s a game made for technology once considered futuristic, and it intentionally evokes how we once dreamed about the future. “We wanted to make a VR game that looked like those early ideas of VR,” said Fish, who also created the popular indie game Fez. “Like Lawnmower Man and Tron.”

The four-person Kokoromi team—which includes Kelley, Fish, Cindy Poremba, and Damien di Fede—is a mix of game developers and academics who met in Montreal, and they formed the collective in 2006 to make games outside of their day jobs. Their projects were experimental, immersive experiences meant to be played at parties, often by people who wouldn’t consider themselves gamers. Their first collaboration was Lapis, a slyly provocative game by Kelley that they adapted for play inside an inverted 360-degree dome; for their Dancingularity event, they wove together a dance floor of Dance Dance Revolution mats that responded to the rising tempo of partygoers feet with increasingly beautiful displays of light and color.

Super Hypercube was born from a 2008 event they organized called GAMMA3D, which challenged developers to make games that would be unplayable without 3-D glasses. At the time, 3-D visuals had become an oft-criticized fad, a way of adding three-dimensional garland to a game but little substance. The challenge was part creative prompt and part question: Was it even possible to make a game where 3-D added something essential?

“We were inspired by our skepticism of the hype about technologies that are supposed to make people to buy something, but don’t necessarily add anything,” said Kelley. When they came up empty on interesting ideas for 3-D visuals alone, they decided to make a game that took advantage of both three-dimensional vision and movement—and Super Hypercube was born.

With a little help from an ingenious YouTube video by computer scientist Johnny Lee, they improvised a pair of 3-D glasses that could also track head movements. This allowed them to do something very cool, something that would also be essential to the wave of VR games to come: the ability to make the world inside the game move in concert with the real-world movement of your head. It became an essential part of the Super Hypercube experience: In order to align the cubes with the corresponding hole, players don’t just rotate them—they have to physically lean left and right to see what lies ahead.

The game was a hit at the Montreal event, and Fish said the team “wanted to take it further,” but there was nowhere further to go aside from other one-off events. They couldn’t sell it commercially when there was no commercial hardware that could play it. It wasn’t until the Oculus Rift emerged in 2012 that Kokoromi realized they’d made a game that was perfectly suited for commercial VR technology—they’d simply made it several years too soon.

Updating Super Hypercube for PSVR gave Kokoromi a chance to fine-tune the game and use the immersive power of the new wave of VR to make a puzzle game that you don’t just play, but also inhabit. “People think they have an idea of what they’re going to experience,” says Poremba. “But unless you’ve tried it, it’s really hard to explain what it feels like to be in there.”

For Fish, who has been vocal about his frustrations with video game culture and expressed a desire to leave the industry more than once, the chance to experiment in the VR space has helped restore some of his lost enthusiasm for making games. “I’m not the only developer out there who was getting a little disillusioned with everything,” said Fish. “Then virtual reality comes along, and it just rekindles your passion.”

“After doing a lot of VR development for like a year, playing a new 2-D game on a flat-screen felt so weird,” said Kelley. “It feels so restrictive to have only this small rectangle in front of my face. That was kind of an eye-opening moment for me.”

“VR reminds me of how video games were 20 years ago, when they were way weirder than video games are now,” added Fish. “The genres hadn’t solidified and people weren’t building on existing. There were no right answers, because everybody was figuring out their own solution and writing the rules as they go.”

Although the launch of the PSVR has been successful thus far, with Sony predicting early sales in the “hundreds of thousands,” skepticism about virtual reality persists among both developers and critics, some of whom predict that the current wave of VR will be yet another fad like 3-D gaming—the exact technology that the original GAMMA3D event had critiqued. But the members of Kokoromi remain excited about VR precisely because they believe it can do what 3-D gaming couldn’t: expand the possibilities of interactive art.

“It’s the Holodeck!” said Fish. “What can we do with that? We can do anything!”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.