This piece originally appeared on Zócalo Public Square.

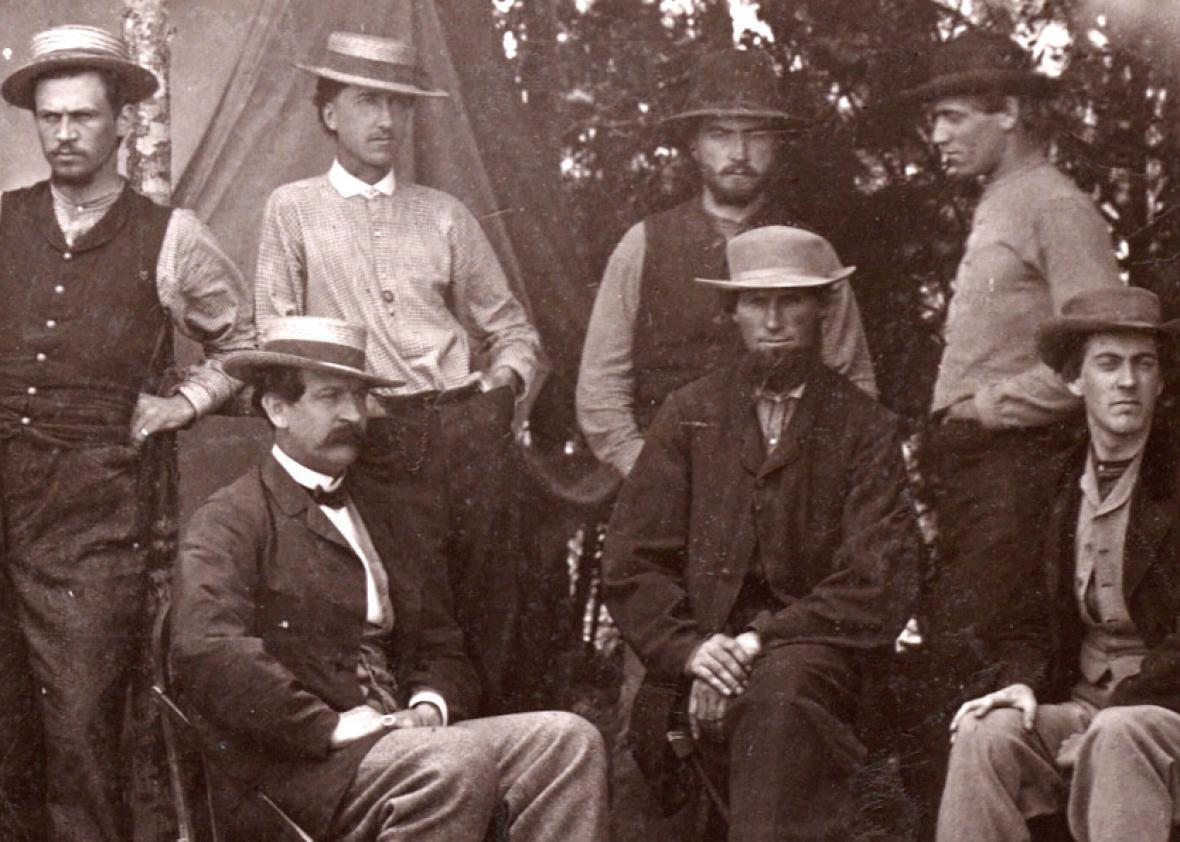

The Thomas T. Eckert Papers—consisting of records, ledgers, and cipher books kept by the head of the War Department’s military telegraph office—came to us at the Huntington Library four years ago via a long and winding road. The collection includes nearly 16,000 telegrams reporting on the U.S. Civil War as it happened, and they are already beginning to tell scholars astonishing things.

The Eckert Papers were initially sold at a private auction in 2009. The sellers were apparently descendants of Eckert’s, and the auction sale was a surprise, because the papers were thought to have been destroyed after the Civil War. In 2012, a documents dealer in New Haven, Connecticut, offered the collection to the Huntington.

On its arrival at the Huntington, we decided that the collection could benefit from a collaborative effort to digitize and transcribe the telegraphs, and in turn the materials could offer valuable teaching tools for the classroom. To that end, the Huntington, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, North Carolina State University, and Zooniverse (a nonprofit devoted to citizen science) applied for a grant from the National Archives’ National Historical Publications and Records Commission to make the telegraphs more usable and discoverable. We also hoped to model collaboration among libraries, museums, social studies education departments, and private software companies.

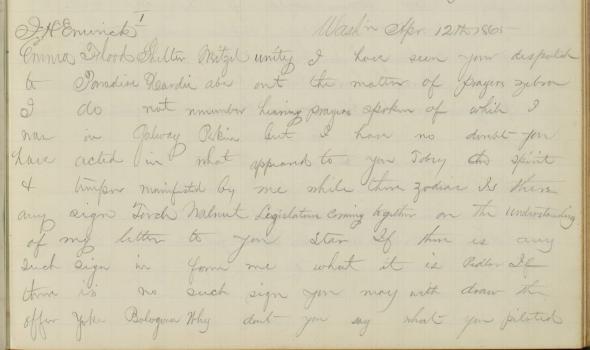

This joint effort has let us engage new and younger audiences by enlisting their services as citizen archivists to help digitize the telegrams. The crowdsourcing component run by Zooniverse has allowed us to recruit about 2,000 interested individuals to transcribe the telegrams with greater efficiency and accuracy than could be done by staff at participating museums. (To find out more about participating in a crowdsourced transcription of these telegrams, visit the Zooniverse website.) The project is also designed to build digital literacy, critical thinking skills, and research proficiency with activities that can be used for many years by classroom teachers and museum educators.

Beyond the historical value these documents carry, their most surprising revelation may be the

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

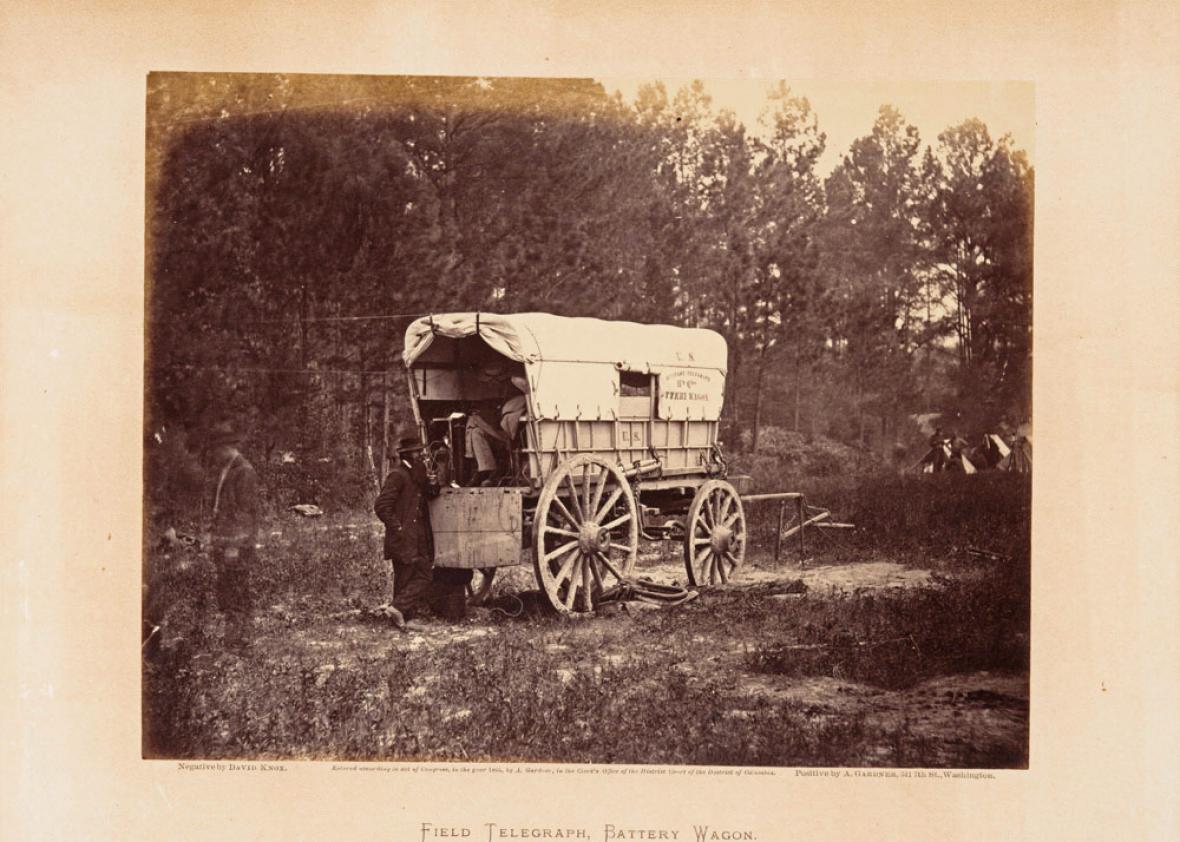

striking resemblance they bear to today’s tweets, emails, and text messages. Most telegrams were written for brevity and tapped out in Morse code: shorthand communiqués, queries, and commands. A great number of the telegrams were coded and proved impossible to crack. They offered the Union almost-instant intelligence about the war and its sweeping, rotating, and seemingly erratic movements and strategies.

Thomas T. Eckert Papers, mssEC 18, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The Civil War’s great, fiery, hour-by-hour drama was played out in hundreds of these dispatches, and things needed doing quickly. Some of the telegrams are riveting in their terseness. “Chattanooga Dec. 6 ‘63,” one began. “Despatch just read from Gen. Foster indicates beyond doubt that Longstreet is retreating towards Virginia I have directed him to be well followed US Grant 4:30 PM.” Those 32 words were issued by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who was just weeks from becoming the commander of the Union Army.

People of all ranks sent messages through the telegraph offices. Soft-spoken Abraham Lincoln was an articulate and eloquent spokesman for his causes, even as brevity was one of his hallmarks: The Gettysburg Address was only 272 words long, after all. The White House was close to the telegraph quarters, making the medium perfectly suited as a communications device for our 16th president. “I HAVE SEEN YOUR DISPATCH EXPRESSING YOUR UNWILLINGNESS TO BREAK YOUR HOLD WHERE YOU ARE. NEITHER AM I WILLING / HOLD ON WITH A BULLDOG GRIP, AND CHEW AND CHOKE AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE,” Lincoln wrote—dare we say texted?—to Grant, by then the commanding officer of the Union Army, just months prior to the 1864 presidential election.

Sometimes telegraph operators helped soldiers and officers transmit personal messages. “A. Lincoln Telegraph lines have been down all day,” one transmission from December 1862 began. “In a day or two our dead are all buried & the wounded are being well cared for the whole Army is in good condition but our loss will much exceed the figures I first named to you will probably reach ten thousand.” The author, “A.E. Burnsides,” then noted that he’d sent a couple of dispatches to his wife earlier in the day, “which I hope you will allow to go through as they are very important to me personally.” This writer, of course, was Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, Lincoln’s commander of the Army of the Potomac. Just three days earlier, Burnside had led the Union army into the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg after considerable prodding from Lincoln. Things were tense, and the note is from a man whose reputation and whose troops had been badly diminished at the hands of the president.

Much like modern emails, the telegrams, stripped of almost all formality, were sometimes emotional but right to the point. In the middle of an Oct. 4, 1863, report to Gen. Henry Halleck, Gen. William T. Sherman mentioned, “My eldest boy Willie, my California boy, nine years old, died here yesterday of fever and dysentery contracted at Vicksburg. His loss to me is more than words can express but I would not let it direct my mind from the duty I owe the Country.” Sherman then returned to his troops on the move, stoically carrying on.

These are the kind of contexts, and subtexts, that appear regularly in the telegrams. The war wasn’t fought on paper or via telegraph lines. It was waged in combat, with blood and indecision and in sorrow—and occasionally, with joy—but almost always with resolute strength. But like modern day iPhone jockeys, the senders and recipients of these 19th-century tweets, and the operators who kept it all working, understood the immediacy of the telegram and the value of instant communication: the things it could do to advance the cause of the war, direct strategic maneuvers, and sometimes, ease pain.

Future Tense is a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.