This piece was originally published in New America’s digital magazine, the New America Weekly.

Most election chatter these days centers around gaffes and polls. However, between Election Day and Inauguration Day, there are 10½ weeks for a new president to get his or her policy agenda in order, and the next commander-in-chief will need to hit the ground running once in office. When it comes to internet policy, it will be necessary to build on the forward momentum that has brought this administration closer to ending the digital divide.

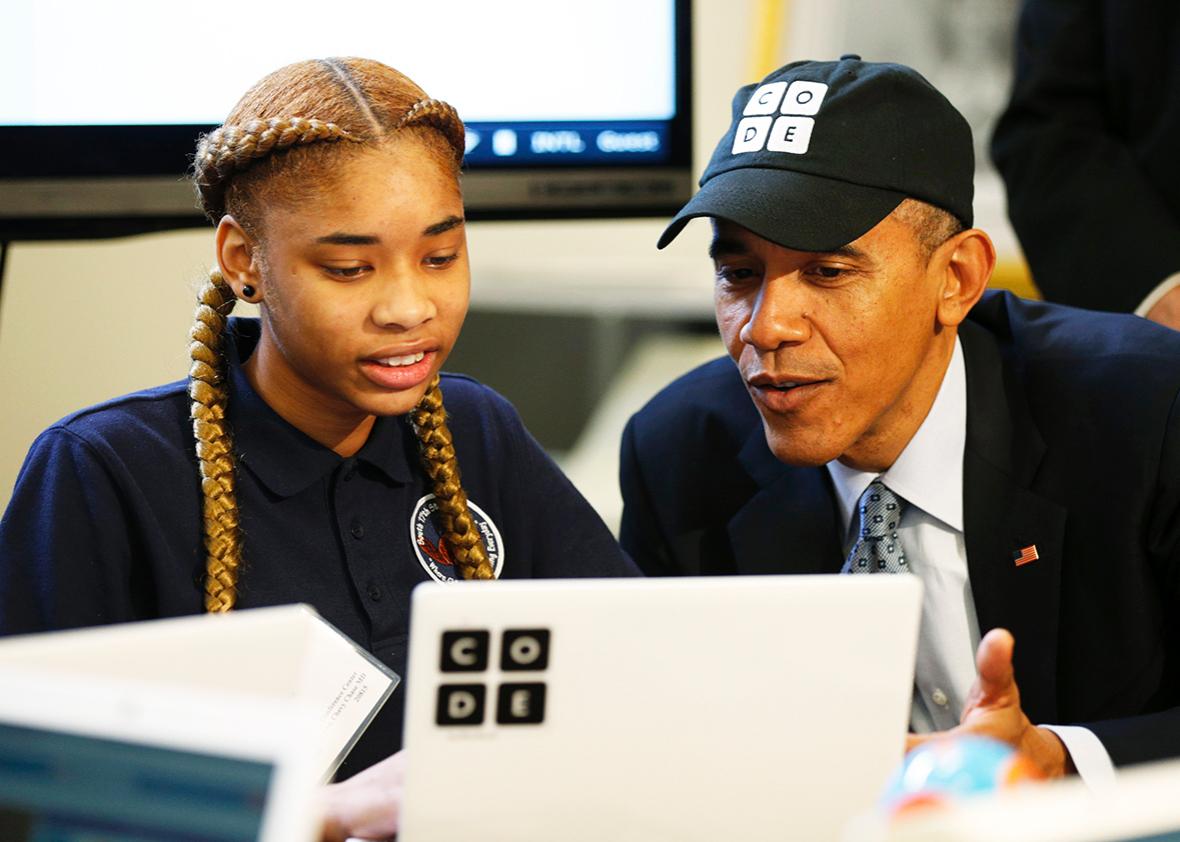

President Obama’s technology agenda was ambitious, particularly on issues such as net neutrality and broadband access and adoption, and his success on those issues is likely to shape his legacy as a technology leader. One of the most important tasks on the next president’s plate will be to resist the temptation to focus exclusively on newer, shinier policy priorities and to instead continue to build on the groundwork that the Obama administration laid to fully close the digital divide.

Perhaps the most notable tech policy win during the current administration was on net neutrality, a concept that ensures that internet users have the ability to access any content they want, without fear of meddling from their internet service providers. This summer, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld the Federal Communications Commission’s historic Open Internet Order, confirming those rules as the established law on net neutrality. President Obama was an early and vocal supporter of strong net neutrality rules, noting that he “will take a backseat to no one in [his] commitment to network neutrality” in a speech in 2007. While the work to achieve these landmark rules was led and supported and ultimately achieved through a broad coalition of D.C.-based advocates, grassroots and netroots organizations, groups representing communities of color, technology companies, and millions of Americans, this win will ultimately help cement Obama’s technology legacy.

The open internet rules, as well as the FCC’s decision to reclassify broadband service as a common carriage service to achieve them, are tremendously important because they create a level playing field for innovation and give everyone the chance to have a voice online. However, they underscore the challenge of ensuring ubiquitous and equitable access to the internet itself. Protecting an open internet is significant, but its benefits will be unrealized if internet access itself is outside the physical or financial reach of so many communities.

For many people, there simply aren’t options for robust broadband service. In the United States, 10 percent of all Americans—roughly 34 million people—lack access to broadband speeds of 25 Mbps, speeds necessary for households to stream high-quality video, use multiple devices over the connection, and generally enjoy the full value the internet has to offer. The statistics are significantly worse in rural communities, where 39 percent—23 million people—don’t have access to broadband at speeds of 25 Mbps. On tribal lands and in U.S. territories, it is worse still: Forty-one percent of people living on tribal lands and 66 percent of people living in U.S. territories lack access to broadband speeds of 25 Mbps.

Availability is only one part of the equation, however. Access is a challenge even in densely populated areas, with 51 percent of households having only one available provider at those speeds. That means only one provider sets the prices and terms of service for entire communities, which in turn means higher costs and lower quality service. A February report from the Cooney Center found that more than half of surveyed families are “under-connected” in some way. Fifty-two percent of parents reported having some internet access but say it is too slow, 26 percent share their computer with too many people, and 20 percent have had interrupted connectivity in the past year after falling behind in payments. For households that access the internet primarily or exclusively with wireless devices (which tend to occur most frequently in low-income communities and communities of color), there are additional challenges such as restrictive data caps and expensive and unexpected overage charges.

As with net neutrality, President Obama made important advances on issues of broadband access and adoption. Most notable was the long-awaited modernization of the Lifeline program, which now gives low-income households the flexibility to use their monthly Lifeline stipend for standalone broadband service. These reforms were part of a broader series of efforts at the administration level that included increasing broadband access in schools, homes, and public housing units.

It may be tempting for Obama’s successor to prioritize new goals and craft an agenda from a clean slate. The next president may say that bridging the digital divide was Obama’s initiative and that we must prioritize new internet policy efforts. But it would be a mistake to ignore the tough but important task of following through on the current administration’s efforts to promote broadband investment and lower barriers to broadband adoption.

Indeed, fully closing the digital divide will be a challenging undertaking, and, as is true with much of policymaking, there is no silver bullet that will bring robust, affordable broadband service to every community. Most critical in this agenda is the promotion and protection of disruptive, community-driven broadband networks. In more densely populated areas, community networks tend to provide better service and increase competition; in unserved areas, they provide perhaps the only means for entire communities to fully harness the power of the internet.

In addition, efforts to lower the cost of service for low-income households must continue. The reforms to the FCC’s Lifeline program are important, but they are just beginning. The next administration will have opportunities to raise the subsidy amount and continue to refine the program to support quality, affordable Lifeline service offerings, as well as to buttress those reforms with digital literacy training programs and efforts to improve competition and lower cost.

President Obama worked to ensure an open, robust, and affordable internet in communities across the country. He made impressive progress. But the next president must ensure that the benefits of broadband access are realized for all communities.

Future Tense is a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.