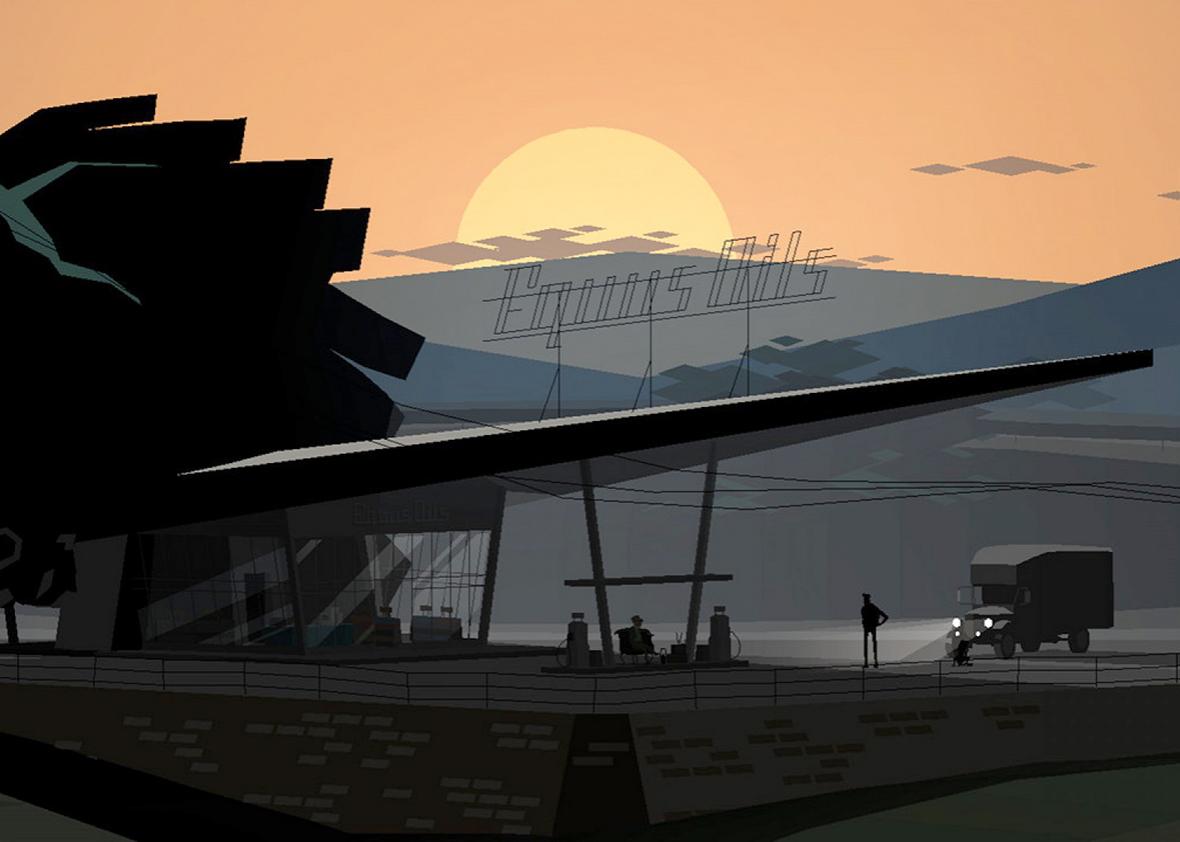

Kentucky Route Zero begins at the end. It’s sunset when an old man named Conway pulls off at a gas station in a truck almost as old as the antiques he’s delivering. It’s just dark enough that Conway leaves the headlights on as he gets out to ask for directions, his aging hound trailing behind him on spindly legs. He has one final delivery to make before the antique shop where he works closes its doors for good, but he isn’t quite sure how to get where he’s going. Nothing on a road map of Kentucky will take him there. “To get there,” the attendant says, “you’ve got to take the Zero,” a secret, underground highway whose arcane route cannot be mapped.

Kentucky Route Zero isn’t like most computer games you’ve played, because there’s nothing else like it. It’s a singularly strange and beautiful experience: a surreal, melancholy journey through the crumbling dream of a lost America. Not the mythical, rose-colored American past popularly championed by would-be demagogues and wistful racists, but the crushing and very contemporary realities of debt and displacement that have left countless ordinary people falling through the cracks of the American Dream.

Released for Windows, Mac, and Linux at a cost of $25 for the four episodes currently out and the one still to come, Kentucky Route Zero’s first act launched in 2013, when the recession of 2008 was still fresh in people’s minds, and the greed of its monied institutions were more visible than ever to the naked eye. The forces that move the characters we meet on their journeys are not curiosity or wanderlust or manifest destiny, but desperation. Like so many of the immigrants that have flocked to America’s shores over the centuries, they are searching for a better life, but finding only a systematic quicksand where the harder you try to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, the deeper you sink.

The world of Kentucky Route Zero is a stretch of Rust Belt twisted into a Mobius loop, a hollowed-out husk of a community full of foreclosed houses, abandoned mines, and lost, discarded people. But it’s also an adventure sewn together with dream logic, full of impossible, non-Euclidean spaces and magical realism that glosses even the grimmest circumstances with a sheen of absurd beauty.

En route to find the Zero, you encounter a young boy named Ezra whose parents abandoned him at a bus stop after getting evicted; his brother is a 30-foot-tall bald eagle named Julian who carries you to a nearby forest. You’re later joined by two traveling musicians, Johnny and Junebug, whose limbs, for reasons that are never explained, emit the hydraulic whir of machinery when they walk. You meet an enigmatic woman living on a foreclosed farm—“I shouldn’t even be here, but I just stayed,” she says—and eventually learn that she’s been sending people messages through their TV sets and might be a ghost. It hardly matters, though, since most of the people you meet seem to be haunting the world in one way or another: squatting in the ruins of their former lives, drifting through the world untethered to anything secure, or shackled to purgatorial jobs that slowly turn them into living skeletons.

“It’s important to us that the game be in, and of, the real, contemporary world,” a member of Cardboard Computer, the development team behind the game, told Vice. “So the characters are living in the world of predatory lending and bizarre, inscrutable financial machinery.”

Conway ends up exploring an abandoned coal mine where a terrible accident claimed the lives of dozens of miners. Much like the narrator of the folk song “Sixteen Tons”—and countless real-life victims of predatory truck systems—the miners were paid not in money but in scrips, little plastic tokens that could only be redeemed at the overpriced company store, a racket designed to drive them deeper into debt and conscript them into permanent indentured servitude.

It’s an experience that is both rarely discussed and frighteningly quotidian; as one author wrote in May about her own very American experience with poverty, “It’s scary being poor, worrying that one parking ticket would mean I couldn’t buy groceries, or deciding whether I should see a dentist about a toothache or pay my trailer park fee. … How many times have we been told to get a job, or that if we just worked harder we could improve our situation? Work harder. Work harder. Work harder. American society has made it perfectly clear: If you are poor, it’s your own damn fault.”

Later, you find a similar system in play at a whiskey distillery full of whirring computers: The employees’ wages are subject to a mathematical formula that calculates the debits constantly charged by the company against their earnings for both necessities and creature comforts, and somehow the company always seems to come out on top. “I’ve got to repay my debt,” says one man after a seemingly inconsequential act leaves him in deep to the distillery. “Hell, I should be glad for the opportunity—if you want to die with any dignity you’ve got to settle up.”

You spend most of Act IV, the game’s most-recent installment, sailing down a river toward a port where Conway can finally make his long-awaited last delivery; he sets out on a boat with a sea captain (who doubles as a doula), a TV repairwoman, a former professor, two itinerant musicians, an abandoned child, and a giant mechanical mammoth. Although your motley crew has the look of adventurers, when you listen to their stories of layoffs, mounting debts, budget cuts and foreclosures, you realize there’s another word for what they are: homeless. Many of them are not setting out for the horizon so much as drifting at the mercy of the current, sheared from their stable lives and communities by the indifferent knife of corporate greed.

The more people you meet as you navigate down the waters of Lake Lethe—named after the Greek mythological river of forgetting—the more you realize this is a place for people who have either lost their purpose or been robbed of it, floating downstream from the banks and factories and mines that discarded them like so much human debris. Although there’s an ad hoc community of houseboats and ships, life without any solid ground beneath you is a precarious one. A quiet resignation creeps across the water, a lethal sense of peace in the idea that their circumstances are beyond their control that feels a bit like accepting death.

Kentucky Route Zero is a paean not only to the broken promises of America, but to the small moments of beauty that manage to bloom inside the cracks of society that people have fallen through. In one of the most moving scenes in the game, you travel to a deserted bar to hear Johnny and Junebug play their music and choose the lyrics line-by-line as their song unfolds. It’s an ethereal moment that lifts the roof of shuddering fluorescent lights off the building, turning it into a celestial amphitheater for one perfect, transcendent moment—until the lights come up and everyone is standing once more in a dimly lit dive with dirty floors.

An emptiness permeates your journey, a sense that we are at the end of a story that is slowly trailing off into silence. Everywhere you go seems either abandoned or about to be, displaced not by the intrusive whims of wealthy gentrifiers but rather the impersonal vampirism of companies who turn people out of their homes not to fill them with anything of value, but simply to leave them vacant on principle, like row upon row of hollow monuments to the power of concentrated wealth.

A murmuring persists throughout the game: first the low rumbling of your idling truck, always waiting in the background, and later the quiet hum of the ship’s engine. It feels like you are always waiting, always journeying, but never quite arriving. And if Conway’s delivery is anything, it is the last vestige of purpose, the last destination worth moving toward when you have nothing to go back to. Although there is still one final chapter of the game to come, the latest installment of this interactive elegy is the most poignant yet, as though it is taking on water and slowly sinking as it glides toward its conclusion.

“The world is not my home,” sings the bluegrass trio that occasionally serves as a Greek chorus, just as the chapter comes to a close. “I’m just passing through.”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.