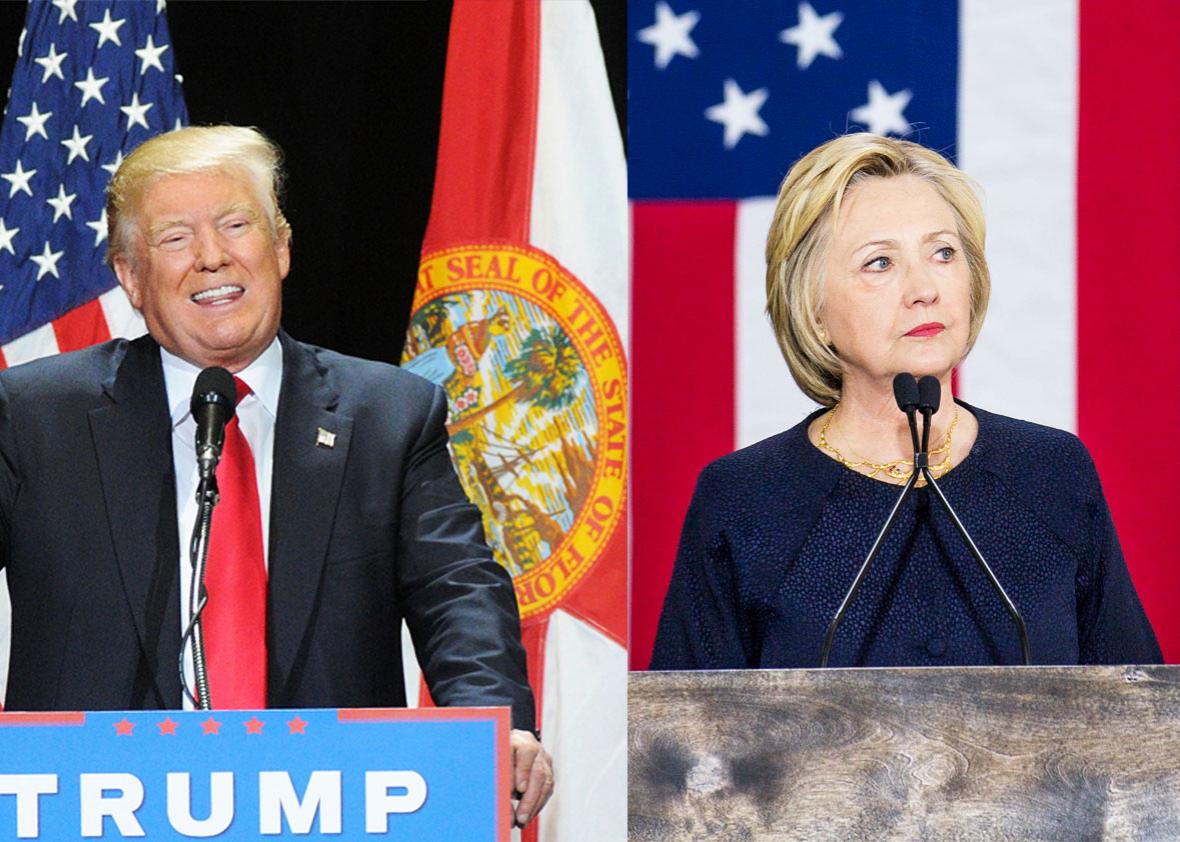

How, in the space of a few years, has “paid trolling” gone from a questionable advertising practice to a political technique being openly used by the U.S. Democratic front-runner?

A press release from Correct the Record, a pro–Hillary Clinton super PAC, announced last month that it has been using a paid task force called Barrier Breakers 2016 to address “more than 5,000 individuals who have personally attacked Secretary Clinton on Twitter.” It plans to increase its funding for these activities through the end of the campaign. From the announcement:

Correct The Record will invest more than $1 million into Barrier Breakers 2016 activities, including the more than tripling of its digital operation to engage in online messaging both for Secretary Clinton and to push back against attackers on social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Instagram.

This sounds a lot like astroturfing, the practice of creating fake grass-roots support by paying influencers to advocate for your views. Allegations of online astroturfing are nothing new—several whistleblowers have come forward to suggest that the Russian government runs a small army of trolls to support its positions on social media—but this is the first time that a super PAC or campaign has made use of astroturfing openly and on such a massive scale. (Update, June 22, 2016: Correct the Record communications director Elizabeth Shappell got in touch after the publication of this article and took issue with the above statement. She wrote, “The investment into the Barrier Breakers program is in personnel and infrastructure. Everyone who is paid for this project is a full-time employee of Correct The Record and is identified as being associated with CTR when engaging with users online.” She declined to answer any subsequent questions.)

From a policy perspective, it is confusing that a super PAC is allowed to make political communications to voters without the accompanying disclosure that the Federal Election Commission usually requires—that familiar “This communication has been paid for by Correct the Record” that you hear during campaign commercials. But several years ago, the FEC made a decision to regulate the internet differently than other forms of communication. At the time, the regulator was concerned that “individuals might simply cease their Internet activities rather than attempt to comply with regulations they found overly burdensome and costly,” and so it chose to err on the side of free speech.

According to Ann Ravel, an FEC commissioner as well as its former chairwoman, the commission has largely declined to update its pre-smartphone era rules to keep up with changing times, and this has allowed savvy political actors to exploit gaps in the regulations.

“The United States Supreme Court has clearly upheld disclosure and anti-coordination by these independent expenditure groups,” Ravel said. “So both of those two principles are clearly agreed to in the law, and it’s frustrating to me to see how we’re carving out a dual campaign-finance system that’s applicable to some but not others.”

As rising chairwoman of the commission in late 2014, Ravel released a statement showing her intent to call a meeting with the public to discuss political advertising online. This statement was a response to a case before the FEC in which a dark money group had released two political attack ads on YouTube. Ravel and her fellow Democratic commissioners felt that these videos should require disclosure and that the cost of production should be a declared expenditure. Because the videos were released for free online, however, the Republican members of the commission voted not to investigate the group, deadlocking the commission and so no investigation took place.*

Ravel made no overt policy proposals in the statement, instead focusing on robust discussion on the issue with experts across a variety of fields. Thinking back to it today, Ravel said with frustration, “it was kind of innocuous.”

In her statement, Ravel acknowledged the FEC’s motive in taking a hands-off approach to regulating online expenditures initially but wrote that, “the Commission failed to take into account clear indicators that the Internet would become a major source of political advertising—dominated by the same political organizations that dominate traditional media.” She concluded with a call to bring together a variety of experts from across the political spectrum to discuss emergent technologies and the commission’s approach going forward in this area.

The following day, Ravel’s fellow commissioner, Republican Lee Goodman, went on Fox News to paint a picture of Ravel’s statement that was anything but innocuous. Goodman ignored the statement’s focus on political advertising—by definition a communication that is paid for—and suggested that unpaid writings might be subject to scrutiny or that the value of online real estate might be counted as an expenditure.

“If we start regulating free YouTube posts, I want you to see what we’d be doing,” Goodman said. “We would be regulating the speech itself and not the expenditure for speech. And so I don’t think we have the regulatory authority to do that.”

A number of other individuals and organizations expressed negative views on the subject as well. Fifteen days into Ravel’s tenure as chairwoman, former Koch brothers money man Sean Noble wrote an op-ed for the conservative site Townhall titled “FEC’s Latest Rule Regulating Online Speech Is Akin to Book Burning.”

Noble’s article attacked the improbable specter of a regulatory framework that would require anyone discussing politics on the internet to register with the FEC. Such a framework might indeed reduce the amount of free speech conducted on the internet, hence “book burning.” In an email, Noble wrote that requiring the disclosures that Ravel advocated for would stifle free speech, and more generally, that “we have less political and public policy speech in the U.S. than we should because of regulations.” He continued:

Requiring a blogger, stay-at-home mom, or college student to register with a government agency in order to write about candidates or political issues would have a chilling effect on free speech. If the goal of the FEC is to “get money out of politics”—which is an absurdity—this proposal actually goes in the opposite direction. By stifling speech of the individual online, they will only empower big business and unions who have the resources to hire lawyers to maneuver the web of federal regulations.

Since no concrete proposal was brought before the FEC, assertions either way about free speech are hypothetical. But we can draw parallels to a similar regulation that was adopted by California’s Fair Political Practices Commission in late 2010. This regulation may help to inform Ravel’s position as head of the FEC in 2015, because she became the head of the FPPC shortly after its adoption and was involved in its implementation.

The regulation, California code § 18215.2, begins by immediately defining what it does not cover. From the regulation:

(b) … Neither of the following is a contribution or an expenditure by that individual or group of individuals:

1. The individual’s uncompensated personal services related to such Internet activities;

2. The individual’s use of equipment or services for uncompensated Internet activities, regardless of who owns the equipment and services.

The text of the code makes it clear that, unless you are receiving money for your work from a campaign or a political committee, you aren’t subject to regulation. Moreover, material I obtained from a Freedom of Information Act request I made via MuckRock for the documentation and discussion surrounding code § 18215.2 suggests that the rule was kept narrow in scope by design. Bloggers and social media users in California do not have to register with the FPPC in order to write about politics, and so far, no team of government regulators has been employed to police writing online. The only practical outcome is that a writer online who is being paid by a California super PAC is required to disclose that relationship to his or her readers.

A federal regulation similar to the one adopted by the FPPC would make the technique that Correct the Record is apparently employing far more innocuous by requiring disclosure. A paid-for political article or a social media post would do far less to confuse readers about true public opinion if it were followed by “Paid for by Correct the Record.” This is important—as voters and candidates’ attempts to reach them move further online, it is likely that astroturfing will only become more appealing if it is left unregulated.

Ravel thinks that a solution is unlikely to come from the permanently gridlocked FEC—its charter requires that no party can control more than three of its six seats, and a majority is necessary for the regulator to act. The Republican members of the FEC have consistently voted as a block to bar any new regulation, and despite several commissioners on both sides having sat past their terms, Ravel’s appointment is the only one made in the last few years.

“They’re just languishing because the Senate doesn’t want to go through the reappointment process and they’ve got people there doing the work that they want them to do,” said Ravel, “Which is nothing.”

*Update, June 22, 2016: This piece was updated to include the context of Ravel’s statement, which came as response to a case before the FEC in which a dark money group had released two political attack ads on YouTube.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.