This piece originally appeared on Zócalo Public Square.

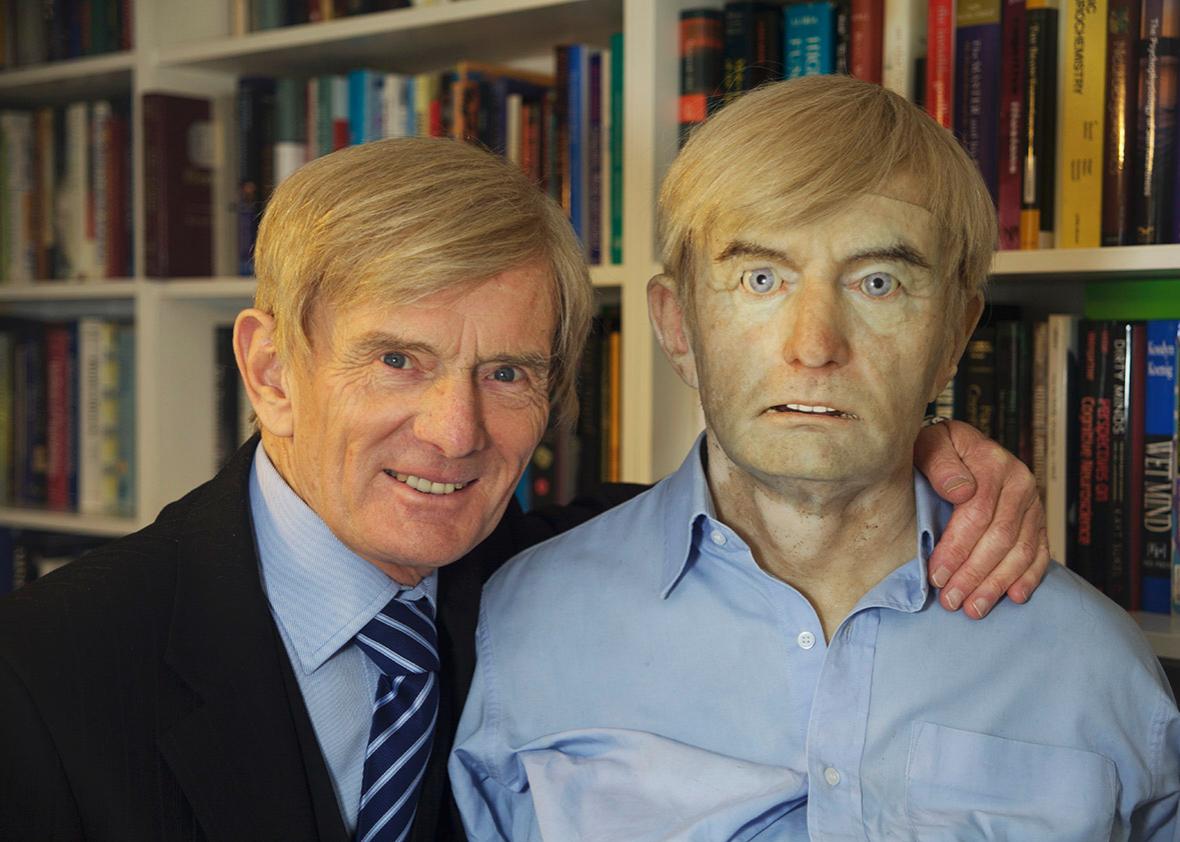

Everybody has one head. I’ve got two!

One sits atop my neck; the other stares back at me. A constant reminder of my craziest-ever impulse buy.

Let me explain.

A few years ago, I impulsively purchased a life cast head fitted out with electronics. My animatronic doppelgänger can blink, wink, and move its lips in sync with my recorded voice. It is an altogether strange and rather disturbing companion that each time we exchange glances makes me wonder what ever possessed me to buy it in the first place.

I tell my astonished friends it was purchased as an aid for the neuroscience course I was lecturing. The truth is I have no real idea why I made such a ridiculous decision. All I can say is “it seemed like a good idea at the time.”

This is a funny thing to say, since I’ve been studying impulsive behavior for years. But when I fell victim to it myself, I was hard-pressed to explain why—and the fact that I’d impulsively purchased an extra head just made it that much harder to explain!

Psychologists categorize modes of thought in two ways: System 1 is nonconscious and error-prone but rapidly able to integrate numerous types of interacting information. System 2 is conscious, plodding, and capable of handling only a few items of information at a time. So with my head purchase, how had System 1 (buy a second head!) overwhelmed System 2 (one head is enough)?

The answer may be “feelings,” the fascinating “third rail” of our two-track way of making decisions. Feelings are hard to define despite the fact they play such a crucial roles in our lives. “While we know without question that we feel it, just how it feels is a good deal more obscure,” writes University of California psychologist Bruce Mangan. “The feeling … is not a color, not an aroma, not a taste, not a sound … (such) experiences are much more diffuse, they have a cloud-like quality that usually spreads out over larger portions of our conscious field.”

Consider, for example, the following controversial topics: immigration, same-sex marriage, genetically modified food, and abortion.

Irrespective of how much you actually know about any of these issues, you will almost certainly have a feeling of “rightness” or “wrongness” about each one.

To get a sense of what thinking by feeling is like, read the following paragraph:

A newspaper is better than a magazine. The seashore is better than the street. At first it is easier to run than to walk. You may need to try several times. It takes some skill but it is easy to learn. Even young children can enjoy it. Once successful, complications are minimal. Birds seldom get too close. Rain, however, soaks in very fast. Too many people doing the same thing can also cause problems. One needs lots of room. If there are no complications it can be very peaceful. A rock will serve as an anchor. If it breaks loose, however, you will not get a second chance.

At first glance, reading this text may cause you confusion, disagreement, or even a feeling of discomfort. While all the words make perfect sense individually and every sentence is grammatically correct, the overall effect is confusing and incomprehensible.

There seems to be no way of making sense of it. But there is: Reread the paragraph keeping in mind the word kite.

I’ll wait for you. … Done reading now?

With a reason, a way to tie the meanings of the sentences together, the text is now clearer, transforming an uncomfortably worded paragraph into an eloquent statement about a beloved toy for all ages. The paragraph feels as right as, previously, it felt wrong, which pretty well defines the essence of this way of “thinking.”

“Fringe” thinking often arises as the result of priming, the practice of using certain stimuli to produce a desired response. Take the following questions, for example: What’s the common abbreviation for Coca-Cola? What sound does a frog make? What’s a comedian’s humorous story called? What do we call white of an egg?

If you answered Coke, croak, joke, and yolk, you’d be wrong.

An egg white is called albumin, not yolk. Coke, croak, and joke primed your brain to focus on a rhyming answer rather than the right answer.

Studies have illustrated the power of priming to affect the way we feel about certain stimuli. In 2008, researchers at the University of Chicago conducted a study that used the American flag to discover how small environmental factors influence political judgment. Two versions of an online survey were distributed to both Democratic and Republican voters, one including a small American flag and one without. The study found that voters who were exposed to the presence of the flag tended to favor the Republican Party, even up to eight months after taking the original survey.

“The effect was not moderated by political ideology or any other measured variable, which suggests that the flag produced the same conservative shift for both liberal and conservative participants,” the researchers commented.

Every type of sensory input forms part of an interconnected network; a particular aroma, for example, may trigger visual, emotional, and possibly muscle memories. Grocery stores often use the smells of coffee and freshly baked bread to trigger impulse purchases among shoppers. But the use of aromas is often more subtle. Some travel agents, for instance, infuse a faint odor of coconut oil into their premises, giving rise to memories of sun-drenched tropical beaches.

Because everyone makes sense of the world in a different way, these sensory-memory networks are personalized to each individual. Even seemingly trivial aspects of an advertisement, marketing strategy, or retail display can cause a flood of positive or negative associations, both conscious and nonconscious, that influence feelings about the message. Feelings arise rapidly and, once established, can prove hard to change.

Which brings me back to my second head.

After having impulsively decided to buy it, I then had to undergo the lengthy and extremely uncomfortable—not to say costly—process of having it made. This involved being smothered in a blue plastic gunk and breathing via straws stuck up my nose. As I waited the 30 minutes it took for the cast to harden, the technician cheerfully recounted how, when making the prosthesis for actor John Hurt in The Elephant Man, the weight of the mold had broken the poor man’s nose.

By this time, the folly of my impulse was apparent, but I became more determined to see it through. Why?

A likely explanation is what psychologists’ call “cognitive dissonance.” This says the more we invest in any course of action, the less likely we are to back off, even in the face of overwhelming evidence that it has been a terrible mistake.

This explanation may be attributed to companies that have foundered and battles that have been lost because those in charge found it harder to admit their impulsive decision had been wrong than to press on and hope that, somehow, it would be all right.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.