When an earthquake hit Ecuador recently, members of the Humanitarian UAV Network, also known as UAViators, launched an appeal for pilots in the region to respond in support of post-disaster search and rescue. UAViators’ founder, Pat Meier, told me that they got replies nearly instantly. The pilot best positioned to respond, Francisco, replied in seven minutes and is “not only based in Ecuador—he took our formal three-day hands-on training on Humanitarian UAV Missions late last year.”

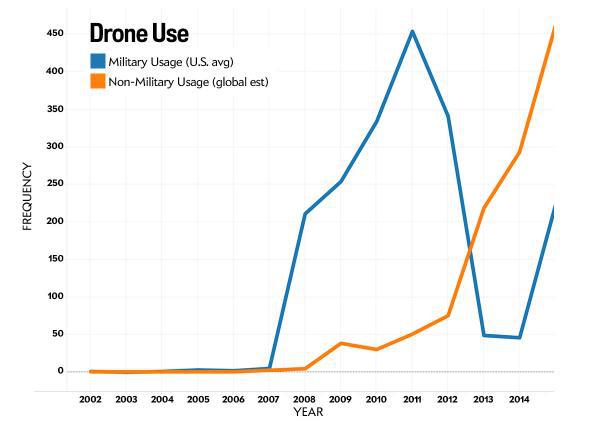

In five short years, small drones have gone from a quiet hobby to a thing everyone seems to be talking about—even Martha Stewart. Drone use has exploded. Advocacy groups such as Human Rights Watch, Open Society Foundations, and Amnesty International have focused considerable energy on highlighting American use of weaponized drones—but what about everyone else? What are they doing?

I recently set out to answer these questions—the who, what, when, where, and why of nonviolent drone use. My colleagues and I plowed through a sampling of reported drone use in newspapers and blogs from around the world—15,000 stories in all. In the end, we had generated the first audit of contemporary drone use, stretching from 2009 through 2015. (You can download the full report and data set here.)

We focused specifically on nonviolent use—no military strikes—reported in English. We did this because we wanted to learn more about small devices hovering over political protests in India; Hungary; and Ferguson, Missouri, and the networks of devices delivering humanitarian aid in Syria and medical aid in Rwanda. Those were the kind of drone uses I was interested in. And that’s the kind of drone use we tracked across these stories.

What we found surprised us. While a host of individuals and institutions were tinkering with drones in the years leading up to 2012, the sheer volume of use took off in that year. Governments, businesses, and individual users together comprise almost three-quarters of the total use. But what exactly were they doing? General hobbyist use experienced the greatest uptick between 2014 and 2015, presumably a reflection of the broad adoption of affordable and easy-to-fly devices such as the DJI Phantom and 3DR Solo. Perhaps more surprising is the fact that over the life of our data, drones were used most for scientific research (17 percent of uses), environmental and wildlife conservation (14 percent), and commerce (14 percent). What we found the least of was the thing people seem to be the most concerned about: nongovernmental surveillance and crime. While we drew on a representative sample of reports on blogs and new reports, we certainly didn’t catch everything—some drone use goes uncovered in the news. Nevertheless, we’re confident that our findings are indicative of how drones are used more broadly.

Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick

At a basic level, the technology is most often used to explore and create. Technologists focused on public good rather than the bottom line—or a desire to balance both—have turned their attention to issues like delivering aid in Syria, finding survivors in the aftermath of the Nepali and Ecuadorian earthquakes, or monitoring pro-democracy protests.

Taken together, this nonviolent use has eclipsed militarized drone use. It may be premature to say we have passed from the era of the Predator—large and lethal birds of prey—to the era of the Phantom—small and versatile tools of the people. But it’s not altogether wrong.

The fact is that everyone is using drones for everything. A tremendous amount of the action in our study was one-off—individuals and institutions experimenting with novel platforms, payloads, and processes. Yet the general trend lines suggest all this experimentation will consolidate into a number of disruptive uses. I say disruptive because drones occupy space in new ways, create new points of access and vulnerability to infrastructure, open new avenues for art and expression, and provide new opportunities for commerce. They also disrupt reasonable expectations for privacy—a penthouse suite still has a great view of the city, but now the city has a great view of the suite.

These threats to privacy (and also, potentially, physical safety) have led the Federal Aviation Administration and states alike to try to rein in hobbyists, entrepreneurs, and others. By our count, as of late 2015, more than 40 laws governing drone use have been passed in almost 30 U.S. states, with dozens of countries passing similar legislation over the past year or two. This number will probably be out of date by the time you read this. The legal team at my own university is scrambling to identify what exactly it takes to come into compliance with America’s lurches toward drone regulation. So far, no clear legislative approaches have emerged, but the general trend is for governments to attempt to regulate the size, altitude, and range of these smaller devices. It’s anybody’s guess how enforcement will work.

While drone laws are up in the air, the devices themselves are being used to enforce laws and protect human rights. Large drones home in on migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border, part of a larger effort by the federal government to monitor areas the Border Patrol cannot reach. Using high-resolution video, they scan the terrain for illegal flows of people and drugs. Rather than the traditional approach of fences, camera towers, and agents, it is drones that now patrol large swaths of desert.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, a Malta-based organization operating out of a converted frigate, has carried two drones on its rescue vessels since 2014. The devices help the organization locate and rescue migrants who have risked the voyage across the Mediterranean Sea. MOAS uses the drone’s thermal and night-imaging abilities to carry out its refugee-finding humanitarian mission. Both of these operations—in the Mediterranean and on the U.S.–Mexico border—have the same purpose: monitoring flows of people across borders. Yet they are doing so for very different reasons.

All of these uses—from humanitarian interventions to state surveillance—are expected to increase in the next decade as the technology proliferates. Public opinions will slowly change, safety issues will start to get sorted out, and a furious round of trial and error will settle into a smaller but more stable stream of developments. The data all points to a sea change in how this platform fits into our economies, our culture, and our lives.

This article is part of the drones installment of Futurography, a series in which Future Tense introduces readers to the technologies that will define tomorrow. Each month from January through June 2016, we’ll choose a new technology and break it down. Read more from Futurography on drones:

Future Tense is a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. To get the latest from Futurography in your inbox, sign up for the weekly Future Tense newsletter.