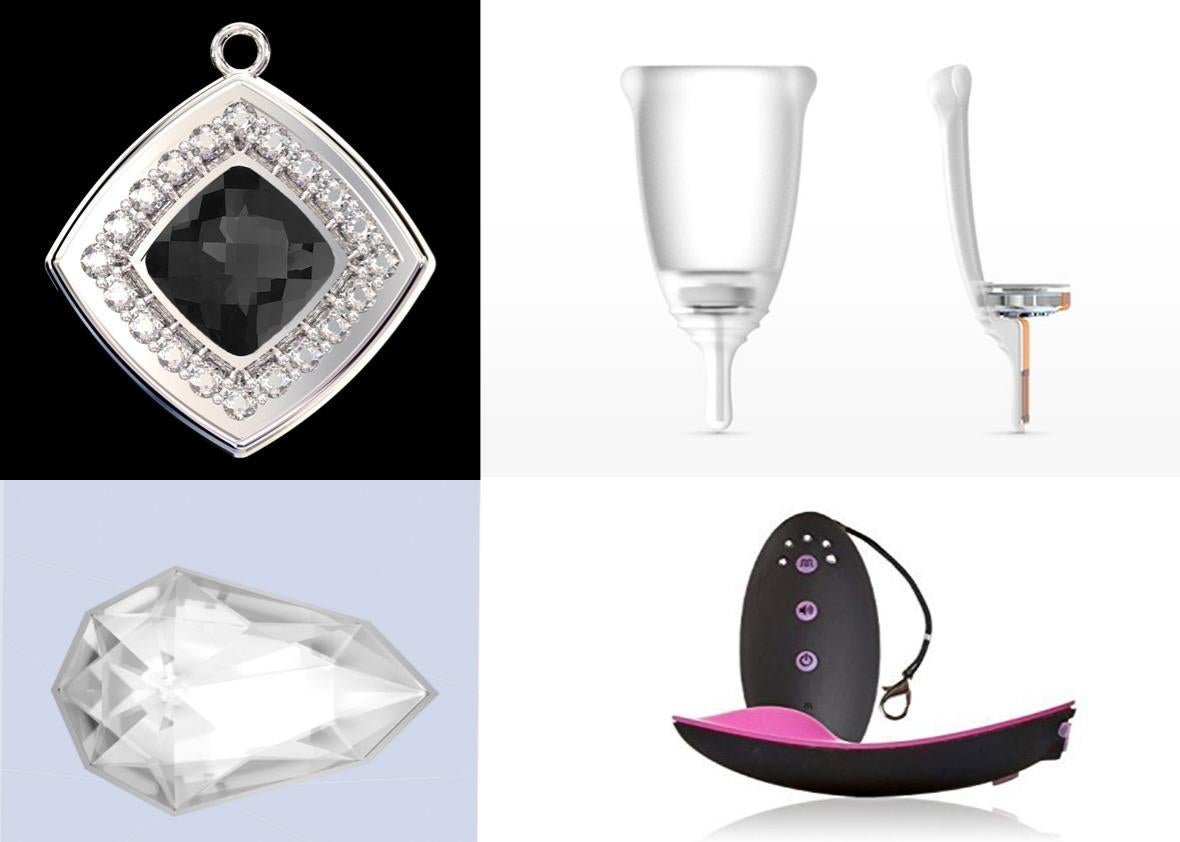

If you’re looking to get away from athletics-inspired wearables, there are more options than ever, especially for women. You can preorder a reusable menstrual cup that requires a Bluetooth antenna to extend outside of the vagina at all times. (Just don’t wear it through an airport security screening.) A nearly $500 MICA smart bracelet, plated in snakeskin and gold and set with semiprecious stones, will let you keep up on email and text messages (provided you pay the annual data fees). You can hang a jeweled security charm from Stiletto on your favorite necklace—the charm promises a safe lifestyle by sharing your location information, indoor or out, with others. Or you can insert a speaker into your vagina to play music for an embryo or fetus.

The U.S. wearables industry is big business. According to the International Data Corp., sales of wearables in 2015 were up 171.6 percent over the previous year; CCS Insight reported that the wearable industries are valued at $15 billion in 2015 and estimated to be worth $25 billion by 2019.

This enormous market thrives by suggesting that teched-up accessories and clothing offer users access to better knowledge, health, and style. But the style and knowledge on offer is highly gendered. While a woman can gather information on athletic performance and basic biometrics just like her male counterpart, she’s more likely to hear from companies that wearables can up her fashion quotient, help her coordinate an outfit, and let her know a loved one is thinking about her or how well her newborn is sleeping. Women’s wearables, small market that they are, remain firmly entrenched in old gender norms that suggest what women want and need is beauty, love, protection, and motherhood.

While the market has moved toward a feminization of wearables giving us smaller sizes and more color, there is still very little out there that takes female physiology or traditionally feminized activity into account in a serious way. Step-counting devices like the Fitbit, which actually measures arm motion while walking, are known to undercount steps when you’re pushing a stroller, grocery cart, or carrying laundry. Mindfulness wearables like Spire suggest that women place the device on a bra band, but it’s hard to feel calm with a device vibrating your sternum.

Menstruation is a major part of many women’s lives and is the subject of much tracking for those who would like to predict fertility or prevent pregnancy, and can impact athletic performance, mood, and caloric intake. Despite this, devices that will integrate menstruation or hormonal information alongside athletic performance are rare and still require manual input. Devices that measure sleep, body temp, and heart rate could all be used to help with both hormonal and fertility tracking, but app developers have thus far kept athletic performance and bodily cycles separate. (The Leaf is a good example of an activity tracker that actually allows women to enter menstrual data via the app, and the new iPhone Health app recently rolled out this functionality.)

In first-generation commercial wearables, most offerings fit a kind of Silicon Valley geek aesthetic—devices were clearly computational and often privileged function over form. Pebble’s fantastically successful first smartwatch was a chunky device modeled on a man’s wrist and more akin to a coach’s stopwatch than a fashion accessory. In the last 10 years, the volume and variety of the products has exploded. But the market remains dominated by devices that are largely targeted for and owned by men. According to one estimate, roughly 70 percent of Fitbit’s profits are accounted for by men.

The 2015 Saatchi and Saatchi Wellness analysis noted that while 95 percent of women are aware of wearable technology, only one-third of them have followed through with a purchase. (The report did not give comparable figures for men.) The wellness study suggests that wearable designers are missing the point with women: They don’t want to “spice up your relationship with a little competition” over steps, miles, or calories—as an earlier tagline from Jawbone suggested. Instead, the study argues that women want to be able to track the many layers of emotional, social and mental health, and wellbeing.

Does the latest crop of wearables for women respond to these desires? No, but they do tell us a lot about what wearable makers think female customers want. Contrary to the Saatchi and Saatchi Wellness study, the industry suggests women want wearables that are pretty and precious. We can further break it down into four conceptual categories: Doing It Better, Safety, Bling, and Babies.

Doing It Better

For many in the Quantified Self movement, which is a community and lifestyle built on the idea that transforming human activity into numbers leads to knowledge, it’s all about knowing yourself better. The market seems to think women want wearables that are all about doing stuff—sex, yoga, sitting, cooking, shopping, and even menstruation—better. Elvie wants to guide women to better sex and health by stimulating better pelvic-floor strength. The Looncup similarly wants to get inside of women in order to “redefine menstruation” (but not in the context of any other activity tracking). Nadi and Lumolift are both about getting into better positions—buzz yourself into correct yogic form or out of that unattractive slouch. I’m all for loving sex with one’s self or partner, but I’m skeptical when I see devices like Vibease and OhMiBod suggest that women need more Bluetooth-enabled, “teledildonic” sex. (Essentially, devices that can be controlled via mobile technologies.) Finally, Neo exemplifies the broad range of smart kitchen devices that promise to make modern homekeeping and food prep frictionless: The device, which the company promises “looks like a jar, thinks like you,” measures volume and calories, calculates servings remaining, and tells you when to head to the store.

Of course, yoga, slouching, and running low on rice aren’t things that only women do, but these sites either exclusively use female bodies in their ads or feature women on the product splash pages. Any of these technologies can be used by men, but these ads foreground women as the target audience for devices to help monitor the body when it’s slipping out of attractive posture or when the feminized pantry starts to run low. By contrast, the product pages for sports-oriented devices feature strong, athletic male bodies exerting themselves in nature, not trying to look better at a desk.

Safety

Assault, rape, and other forms of harassment limit and transform women’s lives. Rather than addressing the underlying issues that make women vulnerable, the wearables market wants us to think in terms of digital tethers or alarms. Many of these devices seem to be as much about tracking our movements as keeping us safe. Safer, Safelet, Amulyte, Stiletto, Bembu, Revolar, and Shadow are all premised on the idea that women will believe a device can keep them safe. Stilleto, “the ultimate lifestyle and security wearable,” will make a computer-assisted call to 911 with a simple touch. Nearly all of these devices operate similarly, with some making a call or sending a text with your GPS information to your personal networks rather than 911. Many of them tout the ability to allow others to follow your movements in real time.

It’s great to recognize that it is hard to dial a phone when under attack. But where are the wearables buzzing would-be–attackers to remind them that rape is wrong? If we can develop devices to correct yoga form and posture, then why not imagine a device that is about behavioral change for perps instead? Behavioral change and profits are more likely to go hand in hand in contexts where survivors and potential survivors are held responsible for their own protection. While I get that attackers are unlikely to buy a device to keep me safe, I’d personally like to see all that innovation go toward ensuring that I don’t need a shadow when walking down the street.

Bling

The Saatchi and Saatchi Wellness study notwithstanding, designers and manufacturers seem to believe that women want their wearables to be more fashionable. Socialite, which promises both health and safety, describes itself as the perfect pairing of “beauty + brains.” From Ringly’s bling for your finger (to keep you away from the phone) to Shine’s Swarovski editions or Intel’s Mica line, wearable companies clearly believe that name-brand designers, snakeskin, and jewels are what women want. Even when industry does seem to build emotional connection into wearables, it comes off as creepy bling—both Mellamor and Gemio tout the ability to change jewels or lights to match an outfit, and both utilize light messaging to let you know when someone else is thinking about you. One person’s glowing warm-fuzzy is another person’s halo of harassment.

Babies

Mimo, Pacif-I, Owlet, and Sproutling all offer to monitor a baby’s sleep habits and vitals and send them to your phone. Pixie Scientific takes it a step further with a smart diaper, which includes a QR code that will analyze “waste makeup and track health information such as hydration levels, infections, and vitamin deficiencies.” While a few of these corporate websites are more gender neutral, the ad campaigns and reporting outlets make it clear that these are designed to be mommy’s new little helpers. Only women’s legs are seen alongside toddlers in smart diapers. Owlet’s video ad features a series of mothers attesting to the lifesaving features of the baby monitor; fathers are curiously absent from these stories of blue-lipped babies and near misses.

A woman can buy into the baby wearables market even before the baby stops baking. The RITMO belly belt is a wearable for playing music in utero but BabyPod, a transvaginal speaker for the fetus in utero, takes this kind of wearable to a whole new level. So when a woman’s Fitbit seems to need recalibration due to elevated heart rates and accidentally reveals a new pregnancy, she has a place to turn when she wants to play that pregnancy playlist.

There’s nothing wrong with bling, babies, safety, or correct yogic posture. There may not be anything inherently wrong in competitive cultures as fostered by more sports-minded wearables, either. But we know that technologies are never neutral. They are intermediaries between our material world, our bodies, and our cultural values. What wearable tech companies are telling us is that they don’t think women are interested in knowing ourselves better in a robust and multifaceted way. Rather, they think that we want to count steps while tethered to monitors at home or need a virtual posture coach to keep us looking our best. These devices suggest that we need to be reassured (at a distance) that people are thinking of us, that others want to have sex with us, and that our children are still breathing. They suggest that we can only feel safe with a direct line to emergency services and that we don’t know at a glance if an infant is distressed or the rice is low. Is it any wonder that women aren’t buying in?

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.