You know that a cultural phenomenon has hit critical mass once a billionaire gets involved. We’ve reached that moment with e-sports, or competitive video gaming. In November, Mark Cuban publicly threw down against Intel’s CEO in the popular e-sports game League of Legends at the Intel Extreme Masters tournament. Shortly after the matchup, which Team Cuban won, Cuban blasted Colin Cowherd, then an ESPN radio host, who had dismissed professional gamers as basement-dwelling nerds while protesting ESPN2’s coverage of a major e-sports tournament.

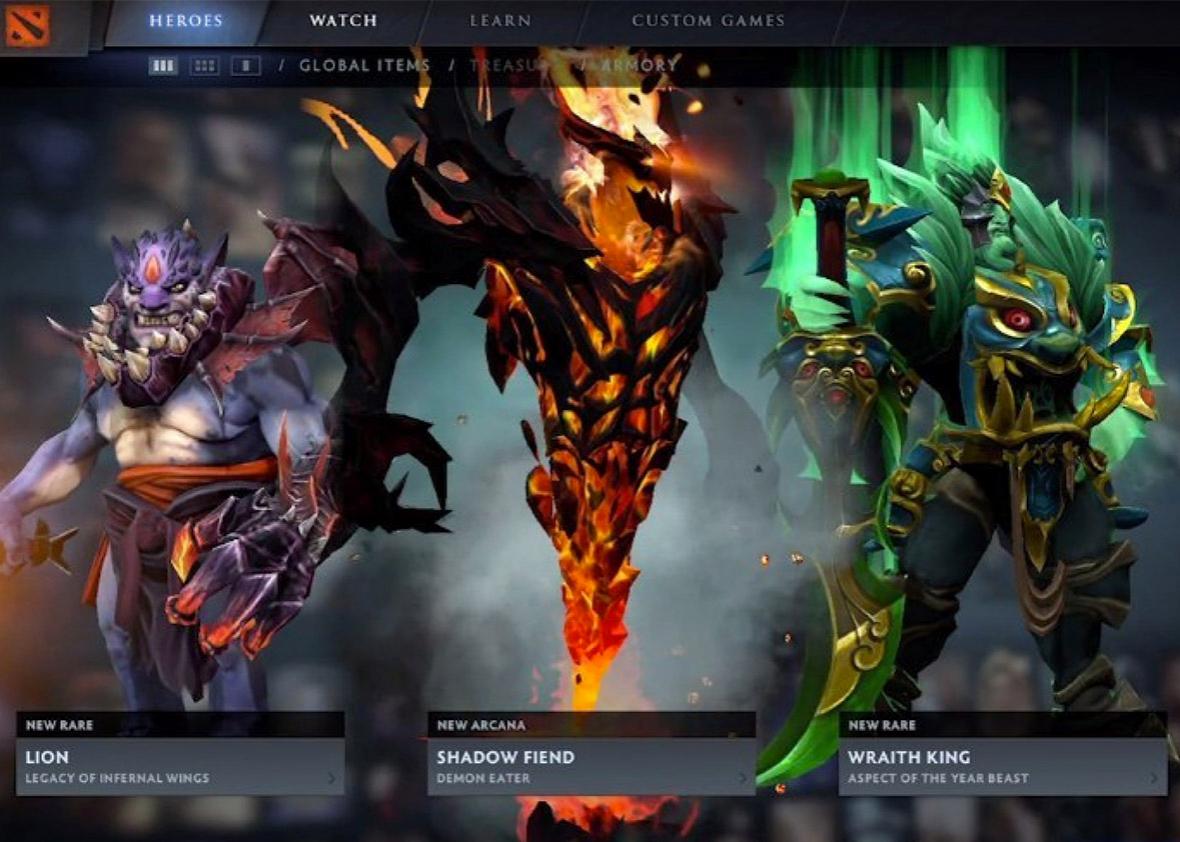

E-sports isn’t the laughable fad it might have seemed to be just a few years ago. And the prizes at these competitions are beginning to match e-sports’ newfound legitimacy. Last year, the team Evil Geniuses won $6.6 million from an $18 million prize pool at the International 5, a competition featuring Dota 2, a game that places teams of supernatural heroes into frenzied combat. Casual observers of the competitions often conclude that they’re merely an inevitable extension of video games—a popular hobby transformed into a global sport.

But the burgeoning e-sports industry is actually built on a small number of games that are uniquely well-suited for competitive play and spectatorship, such as Dota 2 and League of Legends, another frenetic team battle game. The average blockbuster game title, such as the Assassin’s Creed, Fallout, and Far Cry franchises, is driven by a strong, often emotionally charged narrative, with lavish production values and a finite, defined endpoint. But e-sports players spend years mastering specific game platforms and improving their skills through competition, rather than simply consuming products.

The Last of Us, a critically acclaimed blockbuster released in 2013—and then again, with updates, in 2014—is an archetypal prestige video game that has nothing to do with e-sports. It represents the vanguard of the industry’s push for artistic and cultural legitimacy to match its financial dominance of the global entertainment market. In The Last of Us, you progress through a series of closed levels or areas, killing or evading enemies. Interspersed with the stealth-oriented survival horror action are cut-scenes that tell the story of a man who lost his daughter during the zombie apocalypse and now escorts a similarly aged girl across a zombie-infested country. The narrative of The Last of Us is one of the strongest in any video game, and the development of the surrogate father-daughter relationship is moving. But once you hit the end credits, that’s it. You’ve consumed the experience.

In contrast, e-sports games are unending tests of skill and dedication, not the intricately crafted but finite experiences of narratively rich blockbuster titles. E-sports games are more similar to basketball or chess than to The Last of Us, which unfolds like an interactive movie. In Dota 2, you enter the matchmaking queue to look for other people to play with. After choosing their characters, or “heroes,” each team of five enters the set game world. These heroes than attempt to gain strength and destroy a structure in the home base called the “ancient.” When one of the ancients is destroyed, the game world is completely reset, and the player has the option to queue up for another game. Each game pits 10 people in a unique, dynamic competition, so the concept of “finishing” the game does not apply as it does in The Last of Us, Assassin’s Creed, or other prestige titles. There is no limit to the number of times the process can be repeated, because the product is never “used up.” The experience is not consumed. Instead, it’s produced by the players.

A few games, such as the Halo and Call of Duty franchises, offer both rich single-player experiences and competitive multiplayer scenes. When these sorts of games are released, most of their longevity and replay value comes from the competitive aspect. Essentially all high-level play in multiplayer online battle arena games (such as Dota 2 and League of Legends) and first-person shooters (such as Counter-Strike and Call of Duty) occurs on the PC platform—but some great e-sports titles, like Halo and Super Smash Bros., are exclusive to a console, such as Microsoft’s Xbox One or Nintendo’s GameCube.

Like baseball, snowboarding, or wrestling, e-sports balance play and performance. Particularly when you’re just beginning to learn the game, the experience is oriented around play, and you experiment with various techniques. When you’re learning to hit a curveball or sink a jump shot, you need to consciously adjust your form and improve your accuracy. Likewise, in Dota 2, new players need to experiment as they learn “last-hitting,” a specific type of killing blow that ensures that you receive valuable gold from the enemies you defeat. As you develop experience and hone your skills, the competition increasingly revolves around performance, and the winner is the one who can play consistently at a higher level and outthink his adversaries. Basics like last-hitting are automatic, and the games are decided by strategic decisions and precise execution.

E-sports players are not simply consuming whatever is prepared for them by wizardly game developers. They are playing these games hoping to master a craft. If they’re successful, they can begin to contribute to the community that attracted them to the game in the first place. High-level players regularly stream their play to Twitch—a hybrid of a video hosting service like YouTube, a premium cable sports network, and a social media platform—for others to watch. Popular pro players will regularly draw a few thousand viewers on Twitch even during routine public matches. Interacting with viewers and competitors through Twitch chat, e-sports players carefully construct a personal brand. For example, Niklas “Wagamama” Högström is a high-level player widely regarded for his friendly demeanor, willingness to answer questions about Dota 2 between games, and his love for his favorite Dota 2 hero, Templar Assassin. These interactive Twitch streams give casual players opportunities to interact with and learn from elite players—or fellow craftspeople, if you will—in a field they are passionate about.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with prestige, story-oriented games. Indeed, blockbuster games like The Last of Us are catapulting video games into the realm of art, alongside other visual storytelling media like film and television. But playing through these finite, bounded experiences doesn’t lead to becoming part of a community. The surprising popularity of e-sports reminds us that consumers still want to build, create, and perform, not simply consume. These increasingly grand global e-sports tournaments aren’t just about immense prize pools—they’re also celebrations of people who have dedicated themselves to honing their skills, participating in a community of peers, and achieving excellence in something they love.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.