As Zootopia, the latest Disney digital extravaganza, opens on thousands of screens across the country this weekend, another Zootopia remains “in production” in Europe. The animals in this version will be largely unscripted, far less humanlike, and undeniably analog. But its theatrical ambitions will be much the same.

The other Zootopia is a 300-acre expansion of Denmark’s Givskud Zoo proposed by architect Bjarke Ingels and his firm, BIG. A creative mashup of immersive zoo and safari park, Zootopia has been described as a radical reboot of the tired zoo concept: a nearly wall-less and cage-less landscape in which the animals roam relatively freely in multispecies habitats. The first phase of the new park is planned to open in 2019.

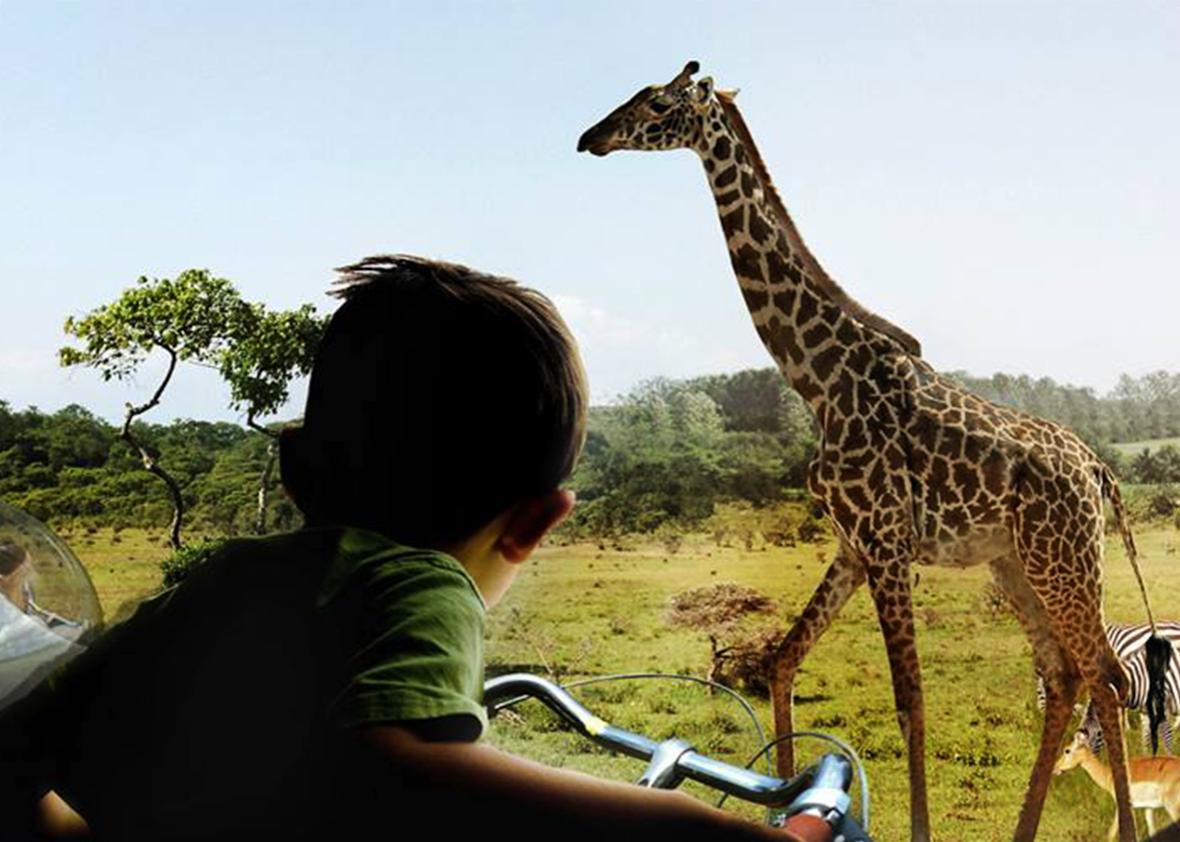

Zootopia’s design philosophy is clearly driven by the goal of minimizing, and in some cases completely concealing, the human presence. Visitors will be sequestered in hidden viewing galleries and transported through the air in mirrored, airborne pods. They’ll also use bicycles and boats to get up close and personal with the zoo’s elephants and zebras, which will be separated form the zoogoers by an ingenious array of natural and mostly undetectable barriers, like strategically placed log piles, bodies of water, and bamboo stalks.

The largest and most discernible human artifice in the park will be the dramatic, bowl-shaped “arrival crater,” a resplendent entry pavilion that serves as a gateway to the zoo’s different “continents” (Africa, Asia, the Americas) and a symbolic entry point to the “wild” environs waiting for visitors beyond the threshold.

Perhaps not surprisingly, commentary on Ingels’ plan has tended to evoke cinematic analogies, including the false-reality conceit of The Truman Show, rendered here as a simulated wilderness that “fools” the animals into thinking they’re on the savanna or in the North American woods rather than holed up in a 300-acre Danish zoological park. And although the Zootopia design was unveiled well before 2015’s Jurassic World, its mirrored transport pods bear more than a passing resemblance to the gyrospheres the film’s characters employ (with less than happy results) to move through the resurrected dinosaur exhibits in the summer blockbuster.

These theatrical qualities are not all accidental. Ingels has admitted that the park’s grand arrival crater was partly inspired by the jungle gate protecting (spoiler alert: not very well) the villagers from the rampaging wild beast in the 1933 classic King Kong. It’s an amusing and perhaps also a disconcerting confession for a zoo design that has already raised some concerns about visitor safety.

Although Zootopia has enjoyed mostly positive media coverage, not everyone is sold on Ingels’ reimagining of the modern zoological park. In his profile “The Dark Side of Zootopia,” New York Times Magazine writer Charles Siebert described it as auguring instead a rather bleak outlook for wildlife and wilderness in the 21st century.

“Ultimately,” Siebert writes, “Zootopia is not a reinvention of the zoo as much as a prefigurement of its inhabitants’ only possible future … a wilderness with us lurking at its very heart.” The new zoo project at Givskud, he concludes, is the manifestation of a wider and more depressing trend: the eclipse of the wild in the human age. Zootopia, in fact, “could well be one of the singular achievements of the anthropocene, a time when human representations of the wild threaten to become the wild’s reality.”

I share Siebert’s worry about the environmental ethic courted by the conceit that we are living in the “age of humans,” an idea that some believe compels us to loosen our commitments to traditional nature preservation. But the notion that wilderness should exist apart from human culture and experience—and that Zootopia somehow violates the integrity of this relationship by offering an illicitly technological and contrived vision of “wild” nature—is also problematic.

Although it’s clear Siebert recognizes that the wild is increasingly subject to the forces of human alteration and control, he nevertheless still seems to be in the grip of a classical ideal of the wilderness: that older, split image of nature and culture that droves of archaeologists, paleobotanists, ethnohistorians, and others have increasingly called into question by documenting the deeper narrative of human modification of even the wilder corners of the Earth. But we don’t need to go digging into pre-Columbian soil to find evidence of this influence.

In the case of the “wildlands” of the national parks, we’re talking about sites that since the early decades of the 20th century have been subjected to extensive scenic and recreational development. These “natural areas” have nevertheless been shaped by generations of landscape architects, planners, and engineers seeking to facilitate mass tourism and accommodate growing visitor access via the building of road systems, bridges, trails, campsites, lodges, and park villages.

Furthermore, for most of the 20th century, the Park Service also groped for a coherent philosophy to guide its wildlife policy as it confronted a host of controversial and challenging issues, from decisions surrounding culling wildlife herds and the introduction of non-native species to the suitability of “unnatural” zoo-like animal entertainments such as roadside feeding of bears and the popular “bear shows” at park garbage dumps in Yosemite and Yellowstone.

The point is that the “real” wilderness values offered as a contrast to Zootopia are nowhere near as ecologically pure or as historically and philosophically tidy as we might think. And of course this isn’t just an American story. As more than a few observers have pointed out, there are fences even in South Africa’s Kruger National Park, barriers that artificially hem in the elephants, lions, and rhinos at one of the most iconic wildlife reserves in the world.

Yet in making so much of the “altered” and anthropogenic character of what we consider to be wild there’s been a tendency to overcorrect, to push the rhetorical pendulum too far in the other direction. Some scientists have argued, for example, that since nothing anymore is truly or fully wild (if indeed it ever was), we should back away from the wilderness as a core concept in environmental protection and focus more seriously on the meeting of human needs, wants, and interests.

Accepting a more nuanced cultural and technological narrative about the wilderness, though, doesn’t require rejecting the idea of there being a meaningful sense of the wild available to us, even in this age of accelerating human influence and control. A remote and roadless stretch of Amazon rainforest is wilder than the enclosures of Zootopia will or ever can be. Zootopia, though, may prove to be much wilder—and wilder in an important sense—than the average zoo, even if its wildness is necessarily qualified and relative rather than pure and absolute.

The response to Zootopia reminds us that zoos today are caught on the horns of a dilemma regarding their relationship with the wilderness. On one end, they continue to be criticized for being too artificial and too contrived. Yet when zoos actually try to become more park-like, natural, and “wild,” they’re often pilloried for falling well short of the mark and for trying to simulate something—wilderness—that some believe simply can’t be replicated.

Ultimately, how we view Zootopia and other future efforts to push the limits of wildness and naturalism in zoological parks depends not only on how we see the prospects of constructing an authentic version of the wild in meticulously designed and managed landscapes, but on how optimistic we are about our ability to maintain respect for what’s taken to be the “real” wilderness on a human-dominated planet. From one vantage point, Ingels’ project is simply another effort to conceal the inherent unnaturalness of the zoo with the latest technological wizardry, a vision that only lowers our expectations of the wild in the process. But from another angle it’s an innovative and exhilarating attempt to inspire different ways of seeing and valuing animals and wild places in the 21st century. It is the parallax zoo.

In the end, I think radically immersive projects like Zootopia embody a difficult and probably inescapable moral friction, one that exists even if we accept a more nuanced view of the wild in the Anthropocene. It’s the growing recognition that we’re both co-inhabitants with other animals and (increasingly) creators of their worlds, including those beyond the zoo walls.

And it’s a tension reinforced by the recognition that our attempts to get closer to other species often only end up reminding us of our distance, and our difference.

A longer version of this essay will appear in the forthcoming volume from the University of Chicago Press, The Ark and Beyond: The Evolution of Zoo and Aquarium Conservation. Future Tense is a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.